Epilogue : the near future

May 5th, 2023 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowThis is the last or concluding draft chapter of Randall White’s political-history work in progress, Children of the Global Village : Democracy in Canada Since 1497. A final version will be published in hard copy by eastendbooks in the autumn of 2024.

* * * *

There is no doubt more than one story of democracy in Canada since the late 15th century. There may even be as many as there are Canadian citizens.

And in the end all such stories are political in some deep sense.

The ultimate conclusion of this story is that Canada’s 21st century democracy still has unfinished business, of the broadly constitutional sort that began in the 1960s and then stopped with the failed referendums on the 1992 Charlottetown Accord.

And this conclusion arrives in a world where political scientist Donald Savoie has in 2019 published his “magnum opus”called Democracy in Canada: The Disintegration of Our Institutions.

Renewing the democratic constitutional odyssey …

very gradually

The Preamble to the Constitution Act, 1867 (still in force, alongside the Constitution Act, 1982) declares that Canada is to have a “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.”

This had a somewhat different meaning in 1867 (also the year of first publication for Walter Bagehot’s classic on The English Constitution) than it does more than a century and a half later.

In a 2021 review of Linda Colley’s book on Warfare, Constitutions and the Making of the Modern World, the distinguished Scottish journalist Neal Ascherson (in the deep wisdom of his late 80s) offered some jagged reflections on the principles of the United Kingdom’s constitution today. And they did not share Walter Bagehot’s later 19th century optimism. (Also the zenith of Gilbert and Sullivan, whose buoyant operettas reminded the economist Kenneth Boulding of the Canada he came to know first hand just after the Second World War.)

In his usual refreshing way Mr. Ascherson urged, for instance, that the “idiotic doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty — the late 17th-century transfer of absolutism from kings endowed with divine right to an elected assembly — excludes any firmly entrenched distribution of rights. Popular sovereignty in Britain is a metaphor, not an institution.”

Ascherson is more sympathetic to the kind of “world’s longest surviving written charter of government” in the US Constitution of 1787-89, as opposed to the largely “unwritten” UK constitution handed down by the late 17th century. A person of broadly similar interests who lives in 21st century Canada may be more reserved.

In the former first self-governing dominion of the global British empire today we have both the unwritten doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty UK or “Westminster” style (1867) and a (“more US/French”) written Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982) — allegedly reconciled via the idiotic “notwithstanding clause” of the Constitution Act, 1982, allowing sovereign federal and provincial parliaments to suspend key parts of the Charter for five-year intervals in particular legislation.

* * * *

On the side of Canada that does still share Neal Ascherson’s admiration for the “world’s longest surviving written charter of government” in the US Constitution of 1787-89, it remains a great and tragic flaw that the “American people” of the late 18th century did not include Indigenous and African Americans.

See eg the last chapter of De Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, volume one : “The Present and Probable Future Conditions of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States.” (And note that De Tocqueville saw “the Anglo-Americans” as the essential creators of the flawed 1830s democracy he so influentially described.) Much more recently see Jill Lepore’s masterful new American history survey (first published in 2018) on even such founding fathers as James Madison — and the Thomas Jefferson who spent his later years after the death of his wife with the mixed-race Sally Hemings, who bore him several children : “none of these men could imagine living with descendants of Africans as political equals.”

Allowing that the reality of the American people has now logically, happily and democratically grown to include virtually all adult US citizens regardless of “race, color, or national origin”(Title VI, Civil Rights Act 1964), one strong-in-theory feature of the US Constitution of 1787-89 is its fundamental grounding in “We the people of the United States.” (And, as explained by the group Americans Overseas today : “A person may become a United States citizen by birth or through naturalization. Generally, if you are born in the United States, or born to US citizens, you are considered to be a US citizen.”)

So the preamble to the US Constitution memorably (if highly incompletely in the 1780s) declares : “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Ultimately it seems more than merely arguable that Walter Bagehot’s English Constitution of 1867 (and Canada’s 1867 “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom”) has this ingredient as well, if when tracing its descent backwards you do not stop at the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89, but go all the way to 4 January 1649.

Just 26 days later King Charles I “was convicted of treason and executed on 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall.” At this highwater mark of the thorniest (and most thoroughgoing) English Revolution the Rump of the Long Parliament had resolved on 4 January that “the people are, under God, the original of all just power,” and “the Commons of England in Parliament assembled, being chosen by and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation.”

Mr. Ascherson might justly remain unhappy with this historic declaration of the Commons of England. And few who try to pay attention may want to think that the toxic shouting matches in the 21st century Commons of Canada too often on TV have any supreme power anywhere.

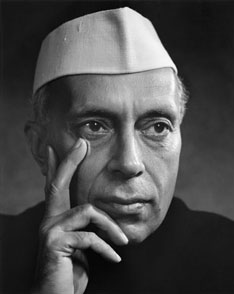

It is in any case the first verse of the Rump Parliament declaration of 4 January 1649 that matters : “the people are, under God, the original of all just power.” (Note as well that the preamble to the present 1950 Westminster parliamentary Constitution of India also begins with : “We the People of India, having solemnly resolved to constitute India … ”) And that now means the decisive supreme power in Canada’s Constitution similar in principle to that of the United Kingdom belongs to all the Canadian citizens, who vote to choose the Members of Parliament in regular if still not altogether predictable elections.

(And, it is worth quietly underlining, the Canadian citizens who also vote to choose policy options offered in three federal referendums so far — in 1898, 1942, and 1992. So Elections Canada today publishes an online table called “Voter Turnout at Federal Elections and Referendums.” The lowest in a Canadian federal election over the period 1867–2021 has been 58.8% of all eligible voters in 2008, and the highest 79.4% in 1958.)

* * * *

How is it then, some might ask, that almost all sensible people know the supreme political power in Canada today belongs to the Prime Minister of Canada? Not in any conspiracy-theoretical sense, but as a plain matter of practical fact. (And as limited and reasonable as Canadian prime ministerial power may often be — as in Ian Brodie’s 2018 account of the Stephen Harper experience he saw up close, At the Centre of Government : The Prime Minister and the Limits on Political Power.)

It can also be said that a strong-prime-minister version of parliamentary democracy has been built into Canadian federal government by what we now call the Constitution Act, 1867. (Or as the Government of Canada website explains today : “The Canadian Constitution places executive power in the King. However, in practice this power is exercised by the Prime Minister and his ministers.”)

As similarly explained by Frederick Vaughan’s 2003 book on the long journey to Canada’s 21st century “reluctant republic,” old Toronto Globe founder (and Liberal/Reform Party leader) George Brown, in a letter to his wife during the 1866–1867 London conference, somewhat unhappily reported that “our Constitution is dreadfully Tory … but we have the power in our hands to change it.”

Brown’s last thought about “the power in our hands to change it” was not exactly true until the Constitution Act, 1982. But Canada’s ongoing unwritten “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom,” guided by a parliamentary sovereignty always and increasingly tilted towards the prime minister, did permit substantial democratic evolution at the hands of Liberal and post Second World War Progressive Conservative governments in Ottawa. And it seems likely enough that George Brown would have approved of at least some main directions.

Meanwhile, the “dreadfully Tory” legacy of the Constitution Act, 1867 lives on — perhaps something else that can nowadays be blamed on the John A. Macdonald who set himself on fire while reading and smoking in his hotel bed during the 1866-67 London Conference (and had to be rescued by his once again indispensable partner, George-Étienne Cartier). In any case Macdonald, who after Cartier’s untimely death in 1873 virtually pioneered the office of Prime Minister of Canada, 1867–1873, 1878–1891, can at least be blamed (among many other things) for starting the strong prime minister model of Canadian federal government.

The model has since expanded. And the recent careers of both Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau suggest that many Canadian voters have ultimately come to believe the office of Prime Minister of Canada today probably does have somewhat more largely unchecked power and influence over the Government of Canada than ought to be, in what the Constitution Act, 1982 quietly alludes to as “a free and democratic society.”

* * * *

The expansion of the strong Canadian prime minister model in the more recent past has also been part of broader international trends. Increasing concentration of power in the prime minister’s (or chief executive’s) office has been a 20th and 21st century syndrome in parliamentary (and other) democracies in many places.

In its part of the broader trend the Canadian political party system is tighter and more disciplined today than it was in the 19th century, in the interests of what was at first called “cabinet dictatorship” over the theoretically sovereign parliament, and then became still more centralized as “prime ministerial dominance.” And as Neal Ascherson urges that the “idiotic doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty” is just “the late 17th-century transfer of absolutism from kings endowed with divine right to an elected assembly,” we have arguably now come to the point where the elected assembly has bequeathed most of its monarchical absolutism to the prime minister (at least elected by the citizens of his or her electoral district).

Beyond the modern prime ministerial command of parliament, even with only minority governments (as Stephen Harper showed brilliantly enough), it is finally the executive power of the more absolute monarch from which much of the prime minister’s present sometimes over-bearing might descends. And this leads logically enough to the remaining vestigial place of the British monarchy in the 21st century Constitution of Canada. (Written and unwritten. And note again : “The Canadian Constitution places executive power in the King. However, in practice this power is exercised by the Prime Minister and his ministers.”)

On the story advanced in this book democracy in Canada today (as more widely recognized in other similar tales) begins with the diverse democratic traditions of diverse Indigenous first peoples and First Nations. To some early modern European minds, they were the original human beings “born free” in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s state of nature. And we are just beginning to understand what Harold Innis urged in a book in 1930 — that Indigenous peoples and cultures have been fundamental to the growth of modern Canadian institutions. On the same story Canadian democracy has continued to grow over the past 500 years. And it is now modern Canada’s decolonized democratic destiny to become an altogether independent parliamentary republic, broadly on the model of such other democratic UN member states today as India, Ireland, Germany, or Iceland (and especially the first two fellow former British dominions).

Some still dispute this destiny, but it is deeply rooted in Canada’s deepest modern history — something often obscured by the continuing “dreadfully Tory” Constitution Act, 1867. Remember, for instance, the New England gentleman historian Francis Parkman who in the later 19th century also noted early Indigenous influences in the old French Canada: “Against absolute authority [of the Sun and other Kings of France and their agents] there was a counter influence, rudely and wildly antagonistic. Canada was at the very portal of the great interior wilderness. The St. Lawrence and the Lakes were the highway to … savage freedom … Their lesson … was well learned, and for many a year a boundless license and a stiff-handed authority battled for the control of Canada.”

Something of a similar struggle, it could be said, carries on even today, in both French and English-speaking Canada, and from Indigenous peoples to the newest Canadian citizens from around the global village. Back in the 17th and 18th centuries, according to the 20th century anglophone historian of Canada or New France, W.J. Eccles, visitors were struck by “the very independent attitude of the habitants,”and “the Canadians’ notorious reluctance to recognize and submit to the authority of their superiors either temporal or spiritual.” And here are at least some deep roots of the free and democratic (if still somewhat reluctant) Canadian republic of the 21st century.

A First Step : Democratizing the Office of Governor General

It is sometimes said by those in the shrinking minority of Canadians who do not want to see an end to the British monarchy in 21st century Canada that this must involve some dramatic and even “basic constitutional” change in modern Canadian democracy.

Yet any introductory survey of the political history of what is now just called the Commonwealth since the First World War will show that this is simply not true. (And again note especially the growth of Westminster-style parliamentary democratic republics in Canada’s fellow former self-governing British dominions of Ireland and India.)

All that is needed is some formal passing on of the monarch’s theoretical as well as practical power to the governor general. (And this has already been prefigured by the 1947 Letters Patent for the office in Canada, the same year the first Canadian Citizenship Act came into force. The Letters from George VI, in theory — and signed in practice by “W. L. MACKENZIE KING, Prime Minister of Canada” — empower “Our Governor General, with the advice of Our Privy Council for Canada or of any members thereof or individually, as the case requires, to exercise all powers and authorities lawfully belonging to Us in respect of Canada.”)

And then the “free and democratic society” in the Constitution Act, 1982 more than arguably implies some kind of democratization of the process by which the governor general is selected. (The reformed office may or may not be given some change of name as well.)

It is also true enough that, in the Constitution Act, 1867 and even the Constitution Act, 1982, the King of the United Kingdom (and present Head of the Commonwealth) is the current Canadian head of state, represented in Canada by the Governor General of Canada. And according to section 41 of the Constitution Act, 1982 an “amendment to the Constitution of Canada in relation to” the “office of the Queen [King], the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of a province” must be “authorized by resolutions of the Senate and House of Commons and of the legislative assembly of each province.”

The failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords of the late 1980s and early 1990s arguably show both the almost terminal impossibility and yet still clear possibility of any such constitutional amendment in Canada.

The ultimate failure of Meech Lake in 1990 demonstrated how hard it is for the federal government and all 10 provinces to agree on anything (let alone the “distinct society” in Quebec). Yet in 1992 at least the governments (if not exactly the legislatures) in Ottawa and all the provinces (and the territories and four Indigenous organizations) did agree on the draft legal text of the Charlottetown Accord (which only failed in two popular referendums — in Quebec and the rest of Canada).

* * * *

Listening to many (well at least some) Canadian political classes, elites, and establishments of the 2020s (in all regions) can illustrate the sharp insight in the late University of Guelph political scientist Frederick Vaughan’s allusion to the aspiring “reluctant republic” in 21st century Canada.

There are Canadians today who reject any long-term future for the “offshore monarchy,” but are still reluctant to altogether embrace a full-bodied Canadian republic. (Some among this esteemed community seem to see a republic as somehow not quite consistent with Canada’s traditional heritage over the longue durée — from Francis Parkman’s The Old Regime in Canada [1874], say, to Richard Gwyn’s two-volume biography of John A. Macdonald [2007, 2011].)

There is evidence for a warmer embrace of the Canadian republic among the broader Canadian people (or peoples). To take just one example, see two opinion polls from the Vancouver-based Angus Reid Institute, in November 2021 and April 2022. Both reported that two-thirds of Canadians (66-67%) do not support continuing with the monarchy after the passing of Queen Elizabeth II (which finally if still somewhat surprisingly happened on September 8, 2022 when the Queen was 96).

In these polls just over 50% of Canadians did not support the monarchy even under the much admired Queen Elizabeth. More than 90% of this growing majority also believed in “Try to change the constitution to cut ties with the monarchy even if it is difficult.” And only a quarter of Canadians (25-26%) answered a bold Yes to “do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come?” (And then, some seven months after the sad death of the Queen, in the spring of 2023 just before Charles III’s coronation, the Ottawa-based Abacus Data reported on a poll result that “2 in 3 Canadians would eliminate the monarchy.”)

Institutionally, the simplest approach to ending the role of the monarchy in a former self-governing British dominion — turning the now domestically appointed governor general into a head of state in theory as well as practice — has, as noted, been pioneered by Ireland and India. In both cases there has also been some democratization in the selection of the new ceremonial head of state (in both cases renamed “president” as well).

In Ireland the democratized governor general has been chosen in a popular election since 1938, among candidates nominated by national and municipal legislatures. In today’s diverse federation and world’s largest democracy of India the new parliamentary republican head of state has been chosen by an electoral college of federal and state legislatures since 1950.

Canadian republicans (and/or anti-monarchists) have also discussed more minimalist institutional options.

On one view these leave any change in the present selection method for governor general (appointment by the prime minister!) to the mid-term future, after a constitutional amendment just doing away with (or “vacating”) the monarchy. Some also argue for (say) approval of the prime minister’s choice for governor general by a two-thirds majority in a free vote of the Canadian House of Commons.

In the end it will almost certainly be important as well to include some role for both federal and provincial legislatures in any democratized selection process for the office of governor general. (And Indigenous governing bodies might be added to this list.) Even in minimalist models of reform provincial legislators could serve as advisors or nominators.

Provincial legislatures may also be more inclined to vote for a constitutional amendment that gives them some role in the selection of the governor general as new head of state. (Moreover, under the Constitution Act, 1867 the governor general in theory appoints provincial lieutenant governors. And this might actually happen at last, as the prime minister loses another of his or her current few too many powers, under the new modestly reformed regime of the democratized ceremonial head of state.)

* * * *

Again the question no doubt continues to bear asking. Can any of this ever happen in 21st century Canada, even long after Queen Elizabeth II has now been succeeded by the less popular King Charles III?

Can the Canadian peoples and their (federal, provincial, and Indigenous) political leaders ever agree on a constitutional amendment politely retiring the monarchy across the seas — and welcoming the slightly reformed all-Canadian governor general to succeed the monarch as ceremonial head of state (under whatever new or old name)?

To believe that this is ultimately not possible — or is at least far more trouble and expense than it is finally worth — is to take a view of Canada and its future with claims to respectability in the first few decades of the 21st century. A certain kind of realism urges that the monarch who lives across the seas plays virtually no practical role in government and politics in Canada today. And, the story goes, it isn’t worth interfering with an already largely democratic political system that works well enough, in any realistic comparative perspective — in the interests of changing something that does not have any great practical impact in the first place.

There is an already quite long tradition of thinking this way, in the spirit of “Canada is a country whose fundamental problems are never resolved.” (And trying to resolve them just makes everything worse!) At the same time, wisdom of this sort probably was good for the future of Canada as it looked in the Age of Mackenzie King, during the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. But it is almost certainly not the best policy for the country’s future 100 years later, in the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s.

Similarly, one apparently strong argument against pursuing any constitutional amendment to end the monarchy in Canada is that, as history shows, once you open up debate on one constitutional issue in the confederation of 1867 others will rush in to demand their own place at the table. And this will finally lead to a bad-karma reprise of the late 1980s/early 1990s Canadian constitutional dead ends.

Yet the realism of this expanding constitutional issue prospect is itself a testament to the ongoing relevance of the ultimate conclusion here : Canada’s 21st century democracy still has unfinished business, of the broadly constitutional sort that began in the 1960s and then stopped with the failed referendums on the 1992 Charlottetown Accord.

And those who want this book to end here should just end here. On the concluding note that a constitutional amendment, turning Canada’s present offshore monarchy and domestic parliamentary democracy into a simpler and more relevant parliamentary democratic republic, is the logical place to begin a broader consideration of the unfinished constitutional business that lies before all Canadian citizens (the original of all just political power), in what remains of the first half of the 21st century!

And those again who do end here should just treat what follows below as a six-part “policy appendix” to the main text. For most readers it can remain happily unread until the Canadian quest for renewing the democratic constitutional odyssey (very gradually) seriously starts to recapture the darker real world — at some point down the road in the new reluctant-republic age of King Charles III of Canada! (Which should probably last not too much longer?)

APPENDIX : Some Constitutional and Related Issues in Canada

The public policy proposals discussed below reflect just one ordinary voter’s opinions, many of which may never see any practical light of day in the darker real world of Canadian politics.

The proposals try to pay some attention to what has gone before — in the spirit of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s “Only a person who knows the past has a future.” More importantly, reading someone else’s struggles with their opinions can sometimes help make a reader’s own more sensible views clearer!

Indigenous Canada and the Constitution

In response to shrewd and strong Indigenous leaders (from a day long before “Indigenous” came into common use), section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 already declares : “The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

Section 35 also notes that : “aboriginal peoples of Canada includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada.” And section 25 in the earlier Canadian Charter Part I of the 1982 Act makes clear that : “The guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.”

Section 25 notes as well that “aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada” include “any rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763” (which immediately followed the first bursts of Pontiac’s Rebellion — and defence of Canada) and “any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.”

Section 35(3) also prescribes that “For greater certainty, in subsection (1) treaty rights includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.”

* * * *

A little of what Indigenous leaders and activists have erected on this constitutional groundwork is suggested by : Paul Martin’s Kelowna Accord of 2005 (abandoned by the Harper government) ; the judicially inspired Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) that took effect in September 2007 ; and Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s June 2008 “full apology on behalf of Canadians for the Indian Residential Schools system.”

More recently there has been Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s sung and unsung struggles to promote Indigenous “Reconciliation” after 2015 — including the appointment of an Inuk (Inuit) governor general ; and Pope Francis’s July 2022 visit to Canada to apologize for the Roman Catholic church’s role in the historic residential schools.

Again, a related potent 21st century trend is the dramatically above-average growth of the country’s Indigenous (or older “Aboriginal Identity”) population. (In the 2016 census the term was still “Aboriginal,” but it had become “Indigenous” by the 2021 census.)

COVID-19 complicated and delayed 2021 census data, as “Statistics Canada struggled to survey more than 600 First Nation and Inuit communities.” For the broader recent past, in 2016 Aboriginal people in Canada, accounted for “4.9% of the total population. This was up from 3.8% in 2006 and 2.8% in 1996 … Since 2006, the Aboriginal population has grown by 42.5%—more than four times the growth rate of the non-Aboriginal population over the same period.”

Some if by no means all of this just reflects increased reporting of Indigenous identity. Statistics Canada projections released in October 2021 were similarly summarized in five “infographics” for each of “Total Indigenous population ; First Nations people [Indian in the 1982 Act] ; Métis [ mixed Indigenous and other] ; Inuit ; Registered or Treaty Indians.”

The variety here reflects one challenge of Indigenous policy in Canada today. On the legal theory adopted when the law of the United Kingdom came to prevail in Canada (except for the old Roman civil law bequeathed by the French regime in Quebec), the country was purchased by the British Crown from its Indigenous inhabitants, in exchange for certain future returns, as part of formal treaties. (The “treaty money” that Harold Innis wrote to his wife about in the summer of 1924 is a case in point.)

One problem with this British imperial and then Canadian treaty system was that it sometimes blended in complex and uncertain ways with the law under the earlier French regime in Canada and Acadia.

Another was that, by accident as it were, virtually no land-purchase treaties had been negotiated in the Colony of British Columbia, that was still majority Indigenous when it joined the new Canadian confederation in 1871. And in all cases after confederation all prior Canadian obligations of the British Crown were ultimately assumed by the new Canadian federal government, which was responsible for “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” under section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

******

Ottawa’s approach to these obligations was traditionally frugal, and it applied only to “registered” or “status” Indians broadly under the terms of the 1876 Indian Act. This is why Statistics Canada still distinguishes “Registered or Treaty Indians” from “Total Indigenous population.”

Similarly again, according to the October 2021 Statistics Canada projections : “The population of Indigenous identity was estimated at 1.8 million in 2016 … it could reach between 2.5 million and 3.2 million in 2041.” And : “The Registered Indian population was estimated at 910,000 in 2016 [just half the Total Indigenous population] … it could reach between 1.1 million and 1.4 million in 2041.”

It is another challenge of Indigenous policy in Canada today that it remains largely focused on the Registered Indian population and, still more particularly, on the more than 600 reserves across the country where this population at least used to be concentrated. Canada at any rate does seem to be moving towards some recognition of an Indigenous level of “self-government,” focused on the reserves.

In its most elaborate form this still somewhat emerging policy concept also envisions significant expansion of the land base controlled by the reserves. It envisions reserve governments as well with the power to extract resource rents from the expanded land base, that could give reserve residents some broad equivalent of the material prosperity enjoyed by the great majority of Non-Indigenous Canadians.

Some reserve governments are happily becoming more involved in traditional private-sector resource economy projects. Yet it remains far from clear that an often volatile Canadian resource economy can reliably give even reserves with expanded land bases a lifestyle similar to that in the more mainstream society, close to large populations.

(The problem seems especially acute for smaller reserves in often still remote places, far from centres of the mass consumption economy?)

******

The broad Indigenous self-government policy thrust is blunted not just by the statistical truth that the current Registered Indian population is only half the Total Indigenous population. In 2016 less than half the Registered Indian population itself was actually living on reserves. Even here the majority of First Nations peoples are now living in the same “off reserve” urban, suburban, exurban, rurban, and rural areas as all other Canadians.

(Though this should not also obscure the growing numbers of young and struggling Indigenous Canadians on reserves, who face difficult and troubling futures over the next few decades, which should somehow be addressed by constructive public policy.)

Much current debate focuses in addition on “healing” from the wounds of the past — especially over the residential school experience. And this is no doubt crucial. At the same time, the broader Indigenous issue has developed to the point where the failures as well as the successes of the past few decades now need frank discussion. The still widely embraced rhetoric of “nation to nation” relations between federal and provincial governments and first peoples’ leaders today may be a case in point.

Back in the year 2000 the University of British Columbia political science professor Alan Cairns, in the conclusion to his book on Citizens Plus : Aboriginal Peoples and the Canadian State, opined : “The momentum behind the drive for self-government and the support for the positive recognition of the Aboriginal presence in Canada are irresistible imperatives to which a wholehearted ‘Yes’ is the only answer. On the other hand, the conditions that sustained the nation-to-nation relations of the early contact period have vanished. Our nation-to-nation relationship then was international. It is not so now and hence to describe it even if only implicitly, without qualification, risks a damaging confusion.”

****

The 2020s are a time of both fresh attention to and growing confusion over Indigenous policy in Canada. At some point soon enough the confusion will have to end. And a new consensus among Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Canadians alike does seem to be somehow evolving or at least brewing.

There may or may not be a related constitutional amendment that will add to sections 25 and 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

Meanwhile, on a very final note, in contemplating Canada after the British monarchy there is also the (only half-serious?) constitutional notion of a perpetually Indigenous Governor General of Canada, chosen every five years (as at present) — presumably from among some such group as all “Registered or Treaty Indians” (or just hereditary and elected chiefs?), and Inuit and Métis too — by the Prime Minister of Canada (on receipt of much well-considered advice from several sources).

Some will say this is not democratizing the office of governor general. It is at least closer to patriating the UK hereditary monarchy itself, in some authentically Canadian form. The Canada that is still, in some degree, in the “straight out of Gilbert and Sullivan” mode in which Kenneth Boulding found it in the late 1940s could probably become a seriously reluctant republic in this way. A country of this sort, however, may not be the kind of Canada that can make it through the 21st century intact!

Quebec and the French Fact in Canada

The great indispensable engine of constitutional change in Canada, from the 1960s to the early 1990s, was the political cause that finally matured into the Quebec sovereigntist movement.

Some will say that many of the issues which drove what began as the Quiet Revolution in the early 1960s remain unresolved, some 60 years later. Just to start with, the provincial Government of Quebec has still not “signed” or otherwise formally agreed to the Constitution Act, 1982. It was passed into law with the assent of the federal government and only nine provinces. (The Act that failed such a test itself still tells Canadians that all 10 provinces must agree on ending the British monarchy in Canada!)

Prime Minister Jean Chrétien had a practical answer here. The Government of Quebec is following the Constitution Act, 1982 when it, eg, uses the section 33 notwithstanding clause to exempt its legislation to protect and preserve the French language in North America from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Whatever else, Quebec is obeying Canadian law — and that may be good enough for most purposes.

Yet there remains an obvious sense in which the Constitution Act, 1982 would be a stronger document if the Government of Quebec formally endorsed it. And the prospect that this could happen, if some further constitutional amendment clarified Quebec’s status as broadly similar to what was not guaranteed by the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords, lingers in the northern North American air.

It is also arguable that (especially since the only narrowly defeated second Quebec sovereignty referendum of 1995?) Canada’s francophone majority province has acquired some de facto distinct society status (or recognition that Quebec really is “not a province like the others”) in practice if not exactly in theory. And this practice was at least endorsed by the Canadian House of Commons on November 27, 2006, when the motion “That this House recognize that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada” — passed by an overwhelming majority of 266 to 16.

At the same time, there is as well the prospect that some similar language could finally be more securely “entrenched” in Canada’s free and democratic regime of law and order by a constitutional amendment.

******

The triumph of François Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) in the Quebec provincial elections of 2018 and 2022 — and the weak showing of the Parti Québécois — suggest some ebbing of the sovereigntist tide in the homeland of the first people who called themselves Canadians. (And this has been reinforced if also sometimes contradicted by opinion polls.)

It remains true enough that Premier Legault is a Quebec nationalist. But this seems to have more in common with the older French Canadian nationalism of Maurice Duplessis, than with the Parti Québécois sovereigntist ideology of René Lévesque (or even Lucien Bouchard).

Another subtle reality peered out between the lines in the 1980 and 1995 Quebec sovereignty referendums. More than a few publicly visible sovereignty supporters still felt that Canada’s vast geography outside Quebec also belonged to them. The western Canadian fur-trade explorer La Vérendrye’s sons were the first people of European descent to see the Rocky Mountains. Identification with the larger Canadian geography that La Vérendrye helped mobilize remains part of the francophone culture that has been evolving in the lower St. Lawrence valley for 400 years.

Since Pierre Trudeau became prime minister in 1968 there has equally been some progress on French-English bilingualism outside Quebec (especially in such places as New Brunswick, the Ottawa region, and Northeastern Ontario). Yet most bilingual Canadians still live in Quebec. And living a life in the French language is not seriously possible even in such large metropolitan regions outside Quebec as Halifax, Toronto, Calgary, and Vancouver. The survival of French in North America today depends largely on what happens in Quebec, not the rest of Canada.

At the same time, “Canada” has a longer history in Quebec than in any other part of the country. (Except for the Acadian survivals in what is now New Brunswick, and the Iroquoian cultures that have handed down the name “Canada” itself.) In some ways francophone Canadians from Quebec are still more interested in the future of Canada than many anglophone Canadians from other parts of the country.

The “National Bank of Canada” is a Quebec francophone project. Canadian prime ministers from Quebec (Laurier, St. Laurent, Pierre Trudeau, Mulroney, Chrétien, Justin Trudeau) have been elected often enough, because more than a few Canadians outside Quebec have seen them as the most effective Canadian leaders. In 2016 only 32% of the population in Canada at large reported their ethnic origin, in part or whole, as “Canadian,” compared with 58% of the population in Quebec!

It is as well almost certainly true that without continuing pressure from Quebec politics and politicians Canada’s Constitution Act, 1982, and its “patriation” of the Constitution Act, 1867 from the Parliament of the United Kingdom, along with several all-Canadian amending formulas, would never have happened. (The same might of course also be said for the failed Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords.)

Back in the 1960s and 1970s two alternative visions of the future of Canada and Quebec were put forward by Pierre Trudeau (guarantee of French language rights across Canada in what finally became the Constitution Act, 1982) and René Lévesque (an independent or sovereign Quebec as a guarantee of French language rights inside Quebec, where the democratic majority of the population still speaks French). In the end neither Trudeau’s vision nor Lévesque’s has altogether triumphed. The long future of Canada and Quebec probably includes something of both!

******

The 2021 Census showed some fresh language trends in Canada. To start with, “one in four Canadians … had a mother tongue other than English or French. This is a record high since the 1901 Census, when a question on mother tongue was first added … Aside from English and French, Mandarin and Punjabi were the country’s most widely spoken languages.”

Moreover : “In 2021, 189,000 people reported having at least one Indigenous mother tongue and 183,000 reported speaking an Indigenous language at home … Cree languages and Inuktitut are the main Indigenous languages spoken in Canada. “

The 2021 Census also reported what Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called some “extremely worrying” French language trends. As explained by Statistics Canada : “French is the first official language spoken by an increasing number of Canadians, but the proportion fell from 22.2% in 2016 to 21.4% in 2021”

More generally, the “proportion of Canadians with English as their first official language” is rising, while those with French is falling. Even in Quebec, “the proportion of the population who speak predominantly French at home has been decreasing since 2001.” Outside Quebec “the number of Canadians with French as their only first official language spoken is decreasing in all provinces, except British Columbia.” And English-French bilingualism “is up in Quebec,” but down in the rest of Canada.

******

On a more upbeat (if not surprising) final note, opinion polls show Quebec is the province most interested in abolishing the British monarchy in Canada. In Angus Reid’s April 2022 survey 51% of the Canada-wide population answered No to “Do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come” (even with Queen Elizabeth II as monarch), and only 26% answered Yes. In Quebec 71% answered No to the same question, and only 11% answered Yes.

(The only other province above the Canada-wide average was Saskatchewan, where 59% answered No and only 22% said Yes.)

Again, in the same survey 67% of the Canada-wide population opposed any future recognition of “Prince Charles as King and Canada’s official head of state.” Separate results by province were not reported on this question. Yet based on the Canada-wide proportions for the situation with Queen Elizabeth still in office, more than 90% of Quebecers would likely oppose any ultimate recognition of King Charles III of Canada! (And yet even so on September 10, 2022 the Government of Canada, via the federal cabinet, officially proclaimed Charles III King of Canada.)

Advocates of a Canadian republic frequently urge that politely ending the British monarchy in Canada will only strengthen the commitment of the Québécois who “form a nation within a united Canada” to the transcontinental confederation, from coast to coast to coast. And this seems a difficult (even impossible?) argument to seriously refute!

Canadian Regionalism and Senate Reform

Staff of the Senate of Canada seem to have traditionally placed a high value on intermittent visits to the House of Lords in the United Kingdom. The still unreformed Canadian Senate is yet another artifact of George Brown’s “dreadfully Tory” Constitution Act, 1867.

Brown himself, however, supported John A. Macdonald’s retrogressive appointed “upper house” of the Canadian parliament — more like the House of Lords in the United Kingdom than the Senate in the United States — on the grounds that an elected upper house could too easily come into conflict with the elected “lower” House of Commons. (Australian parliamentary democracy, on the other hand, has since 1901 lived with an elected Senate without suffering from this kind of conflict — partly because its constitution has a mechanism to resolve it.)

Such other fathers of confederation as the future Ontario premier, Oliver Mowat, favoured carrying on with the arrangements for the old upper house of the Legislative Council in the United Province — which had been made an elected body in 1856. (George Brown had opposed this as well because, in the words of historian J.M.S. Careless, he held it “unsuited to the British system of government responsibility to one elected body.”)

Whatever else, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries reform at last of what Robert A. MacKay had called The Unreformed Senate of Canada in 1926 became an issue with resonance in Western Canada, especially in Alberta. And the Prime Minister Harper who rose from the 2006 federal election as MP for Calgary Southwest aptly enough called the upper house prescribed in the Constitution Act, 1867 “a relic of the 19th century.”

******

On the surface the main appeal of Senate reform in Western Canada in the late 20th and early 21st centuries was (and still is?) its appearance as a change in federal political institutions that would give “regional” provinces extra weight, in face of the more than 60% of the Canadian population in the two “central” provinces of Ontario and Quebec (61.1% according to Statistics Canada’s estimates for the fourth quarter of 2022).

One of the unhappy legacies of the 19th century, that is to say, has been a degree of old United Province of Canada imperialism in the confederation of 1867. And this has been rubbed especially raw by the post 1867 growth of the Canadian West — amplified by the blossoming Western energy economy after the Second World War. (While Atlantic Canada, the original confederation protest region, now at least has more unreformed Senators — 30 in fact since 1949 — than anywhere else.)

Harold Innis implied a deeper and more complex case for Senate reform in Canada in a 1943 journal article on “Decentralization and Democracy.” An overhaul of the upper house in Ottawa was arguably the answer looming behind such Innis pronouncements as : “Provincialism has parallelled the new industrialism … Confederation as an instrument of steam power has been compelled to face the implications of hydro-electric power and petroleum … Strains on the political structure have been evident on all sides as problems of adjustment have become more acute.”

Or (to quote again from Innis’s 1943 article) : “The complex problems of regionalization in the recent development of Canada render the political structure obsolete and necessitate concentration on the problem of machinery by which interests can become more vocal and their demands be met more efficiently … serious attention should be given to the problem of revising political machinery so that democracy can work out solutions to modern problems.” Improving regional representation by making the “unique institution” of the Senate of Canada more effective is one obvious enough approach to the requisite “revising” of “ political machinery.”

From yet another related point of view, the title of an influential 1985 report from a Special Select Committee of the Alberta legislature was Strengthening Canada: Reform of Canada’s Senate. As matters still stand now, the main political machinery for managing Canadian regionalism involves provincial governments and intermittent First Ministers’ meetings of federal and provincial government leaders. And this finally weakens the role of the federal government in the larger confederation.

Serious reform of the Senate in Ottawa could provide political machinery for managing regionalism inside the institutions of the federal government itself. And this would arguably finally strengthen the federal government in Ottawa, by directly incorporating regional interests in the federal policy-making process. Senate reform of this sort would “Strengthen Canada,” as the authors of the 1985 Alberta report urged.

******

The 1985 Alberta report, inspired by at least a few wider currents in Canada’s fourth most populous (and oil-and-gas-rich) province, suggested a particular version of Senate reform, built around something popularly known as a “Triple E” Senate (Elected, Equal, and Effective).

In practice this was no more or less than the Senates already existing since the early 20th century in the federal systems of the United States and Australia. These were (and still are) elected bodies with equal representation for each state in the federation (province in Canada’s case) — and with some real power in federal government decision-making.

One key problem with the concept of equal provincial representation in Canada is that Quebec, as the only French-speaking majority province in the confederation, has always seen itself as “not a province like the others.” Another is that Ontario can have a hard time understanding how its 15.3 million people (Q4 2022) are in any reasonable sense “equal” to the 173,000 people in Prince Edward Island.

Still another is the more general problem of what the US journalist Alexander Burns has called “the rural bias of the American republic” — in a 21st century with an urban and suburban democratic majority. This bias has been induced in the USA by a Senate with equal state representation, in a federation where state populations range from somewhat more than half a million people in Wyoming to some 40 million in California!

On any deep examination in the 21st century even British Columbia and Alberta do not have any real interest in a reformed Senate of Canada with equal representation for each province. (And then there are the now three northern territories as a further immediate regional complication.)

In fact the fundamental regional division in the Canada of the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s is not between Ontario and Quebec (themselves quite divided by majority language) and the eight other provinces, but between the four more populous provinces of Ontario, Quebec, BC, and Alberta, on the one hand, and the six less populous provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, and PEI, on the other. A provincially equal Senate would give a majority of seats in the reformed body to the six least populous provinces, currently home to just over 13% of the Canada-wide population.

With no doubt some grasp of complexities of this sort, Stephen Harper’s government did not even try to implement the “Triple E” model. The much more gradual Harper reform plan focused on the E that stood for Elected. Starting in 1989 the provincial Government of Alberta had held so-called Senate consultative or nominee elections. Brian Mulroney’s Conservative federal government had appointed the first winner of the first of these Alberta contests to the Senate. Harper himself would appoint four more. And federal legislation promoting such provincial Senate elections Canada-wide was at the heart of the gradualist plan Harper’s government finally sent to the Supreme Court, for an opinion on constitutionality.

It was also central to Harper’s reform plan that it could all be accomplished without any troublesome constitutional amendment requiring some form of provincial approval. Yet the Supreme Court’s opinion was that very little in the plan could be done without some form of constitutional amendment — and that certainly included Senate elections. Though what PM Harper might have done on revised Senate reform plans if he had been re-elected in 2015 is unknown, the Supreme Court reference announced in April 2014 did put an end to his original strategy.

******

Seeing the broader issue as something that something must finally be done about, the Justin Trudeau Liberal government that won the 2015 election soon enough launched its own quite different Senate reform plan. This, as it were, drew on Harold Innis’s 1940s view that the “Senate, that unique institution, has lent itself to political manipulation.”

Innis further argued, like many others more casually, before and since, that the unreformed Senate essentially appointed by the prime minister of the day “provides … a support to party organizations throughout Canada … A senator stands as a guard over the party’s interest and is expected to be continually alert to the improvement of the party’s position in the region from which he is appointed.”

The Trudeau Liberal Senate reform plan focused on this key criticism. Senators who were supposed to provide a so-called upper house of “sober second thought” on legislation from the more partisan lower house were just patronage appointees, working to support the narrow institutional interests of the political party leaders who appointed them.

At the same time, like Stephen Harper, Justin Trudeau did not want his reform plan to wade into anything as challenging as a constitutional amendment. The prime minister would continue to appoint Senators, but on the basis of advice from a more neutral and higher-minded board. And the governing party at least would end its partisan ties to any Senators.

Whatever else, this Trudeau Liberal Senate reform plan has changed the way the Senate of Canada operates. As of early 2023 the current 105 Senate seats were allocated among six “political groups” : Independent Senators Group (39) Conservative Party (15) Progressive Senate Group (14) Canadian Senators Group (13) Non-affiliated (12) and Vacant (12). This somewhat revised Senate is taking its job more seriously. The new worry may be that the more power it tries to exert, the clearer it becomes that it remains an appointed body which cannot risk being too “effective.”

Still more fundamentally, if the revised Senate in action in the 2020s is in fact at least less of a blindly partisan retirement club for aging veterans of the democratic political wars, it is, if anything, even less of a representative of regional interests in federal decision making than it used to be. And the allocation of seats still flows from the original design of 1867 (based in turn on the old Legislative Council in the United Province of 1841–1867) : Quebec 24 seats, Ontario 24 seats, Maritime Provinces 24 seats (NS and NB 10 each, PEI 4), Western Canada 24 seats (each of four provinces 6 seats), Newfoundland and Labrador (which joined in 1949) 6 seats, and finally 1 seat for each of three current territories.

******

Ultimately electing effective Senators from a revised and sensible allocation of seats among provinces and regions is the logical path ahead for the kind of enduring future reform that would require a constitutional amendment. And it is not difficult to invent logical regional reallocation schemes that would in theory improve regional representation, while avoiding the kind of pronounced “rural bias of the American republic” induced by equal state or provincial representation.

To start with, for example, give each province 3 senators. Then double this allocation for provinces with 10% or more of the Canada-wide population. (Alberta, BC, Quebec, and Ontario, that is, have 6 seats each.) Then double Quebec’s representation as the only province with a francophone majority. (It ends with 12 seats, while Ontario, BC, and Alberta still have 6 each. All other provinces have 3 seats each.) Now add 3 more seats — one each for the current three northern territories. Finally, add another 3 seats for some institutional Indigenous representation.

Again in theory this arrangement would give a 54-member Senate of Canada that brought regional interests directly to bear on federal government decision making — without fundamentally compromising the one-citizen-one-vote democracy of the Canadian House of Commons. And this could also increase the popularly perceived legitimacy of federal government institutions in more skeptical regional geographies. (Some explicit mechanism for resolving conflicts between the upper-house Senate and the lower-house Commons would no doubt be prudent as well.)

It may be at the same time quite difficult to imagine practical circumstances in which real-world Canadian federal and provincial governments could and would agree on some suitable regional reallocation of seats in a new elected and effective Senate of Canada. The requirement for a constitutional amendment here is only approval by the federal parliament and seven provincial legislatures, representing 50% of the Canada-wide population. But even with such advantages in the Canadian real world a successful reformed Senate could prove more elusive than unanimous provincial agreement on the details of a new independent ceremonial head of state, to succeed the British monarch.

Another Referendum?

In Canada’s “written constitution” a constitutional amendment today typically requires the approval of federal and provincial legislatures.

(The general formula, which applies to Senate reform, is approval by the federal parliament and two-thirds of provincial legislatures representing at least 50% of the Canada-wide population. The more restricted formula — which applies to the monarchy, governor general, provincial lieutenant governors, and any actual abolition of the Senate — is the federal parliament and all 10 provincial legislatures.)

The precedent set by the (ultimately two) popular referendums that finally defeated the Charlottetown Accord in the fall of 1992, however, may mean that approval in a popular referendum for any major future constitutional amendments — on the monarchy, Indigenous rights, Quebec and French Canada, Canadian regionalism and Senate reform, and/or anything else — has now become part of Canada’s “unwritten constitution” in some grand new Westminster tradition.

In the end it will be the political leaders who negotiate any future constitutional amendments who decide whether the 1992 referendums have set an unwritten precedent that applies to whatever particular cases may be at issue. Whatever else, there is at least some precedent for a referendum related to some constitutional amendments in Canada. And there is clearly a broad philosophical argument that this would be appropriate in what the Constitution Act, 1982 calls “a free and democratic society.”

******

There is another somewhat different argument for a referendum in advance of a constitutional amendment, as it were — in an effort to let the people urge the politicians in federal and provincial legislatures to take action.

This prospect is often raised in discussions about the future of the British monarchy in Canada today. And Canada’s fellow “Commonwealth Realm” of Australia did hold a referendum on the future of the monarchy down under in 1999.

In contemplating a Canadian referendum following the spirit of the Australian model, it is worth bearing in mind that “constitutional alterations” proposed by the federal government in Australia must be legally and constitutionally “submitted to the electors” of the federation in a referendum, in order to become law. (And, as of the early 2020s : “Of the 44 referendums submitted to the electors since Federation [in 1901], eight have been approved.”)

Put another way, in the Australian amending formula Canadian approval by provincial governments representing a majority of the Canada-wide population turns into a more direct approval by a majority of the Australia-wide electorate (where voting as in other contexts is compulsory by law!). In a Canadian referendum in advance of a constitutional amendment even a Yes vote (on abolishing the monarchy, eg) would not in written law mean that federal and provincial legislatures (or sovereign parliaments) had to do anything. Politics or even the unwritten constitution would of course be a different matter : a very strong Yes (or Non) vote in all provinces would at least be hard for elected politicians to ignore.

******

As noted here earlier, the federal referendum on the 1992 Charlottetown Accord (held in all provinces except Quebec, which held its own referendum on the same question and same day) is only one of three federal referendums (or as the Canadian Encyclopedia wisely points out “more strictly, plebiscites”) held by the confederation of 1867 so far.

The wisdom of the Canadian Encyclopedia is also worth quoting in full on the two earlier cases in point : “The first was in 1898 on the issue of Prohibition; only 44 per cent of the electorate voted, with 51 per cent voting Yes for a prohibition on alcohol and 49 per cent voting No”.

The Encyclopedia goes on : “Ultimately, the government of Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier decided that the majority of more than 13,000 Yes votes was not large enough to warrant passing a law, especially since Québec had voted overwhelmingly against Prohibition.”

And then : “The second federal referendum was on conscription in 1942. The Liberal government of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King asked Canadians if they were in favour of releasing the government from its promise not to use conscripts for overseas military service in the Second World War. More than 60 per cent of the voters replied Yes; the others, No. In Québec, however, about 72 per cent voted No.”

******

It could be said that there is one side of Canadian political culture, especially at the federal level, which looks askance at all popular referendums as inherently divisive, in a country that already has almost too much dividing it.

Put another way, the old empires live on, in continuing feelings that business or economic, cultural (including religious), and government and political leaders know best. And this is reflected in the complex enough amending formulas of the written Constitution Act, 1982, which (unlike the written Australian constitution) nowhere calls for any popular referendum as part of the formal process of constitutional amendment.

And then, at the same time, there is another “unwritten constitution” side of Canadian political culture — descended in part from the old multicultural and multiracial wilderness freedom of the transcontinental northern fur trade, say, and especially strong at the provincial level. (And as the Canadian Encyclopedia notes as well : “Although federal referendums are rare in Canada, there have been numerous provincial referendums and plebiscites since Confederation.”)

This side of the room sees a stamp of approval from the Canadian people (or peoples), in a popular referendum, as an important feature of any major new directions mandated by constitutional amendments. This led to the failed referendums on the 1992 Charlottetown Accord. And it may finally lead to referendums on any similar occasions in the future as well.

The new Commonwealth and La Francophonie?

In some ways what is now just known as “The Commonwealth” seems to be a less and less important heritage memorial to the old British Empire. (And then British Empire and Commonwealth and then British Commonwealth of Nations and then Commonwealth of Nations!)

In the very early 20th century the French geographer and political writer André Siegfried could imagine that the British Empire of that day would long remain a common-sense condominium for the old French Canada. But this made virtually no sense in the Canada and Quebec of the 1960s and 1970s ultimately inspired by René Lévesque and Pierre Trudeau.

In pursuit of some more up-to-date world view Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s Canada was an enthusiastic “founding member” of “La Francophonie … established on March 20, 1970, at the Niamey Conference in Niger, with the creation of the Agency for Cultural and Technical Cooperation (ACCT), which became the International Organisation of La Francophonie (IOF) in 2005. The IOF is now at the centre of a network of organizations that make up the institutional Francophonie.” (Government of Canada, “Canada and La Francophonie”).

At first La Francophonie was seen in Ottawa as an international organization that could play for French Canadians the role the Commonwealth had traditionally played for English Canadians. More recently all varieties of Canadians, the Commonwealth, and La Francophonie have been transformed by further waves of T.S. Eliot’s many cunning passages of world history. And in some serious degree what remains of the old European empires is (quite rightfully and encouragingly) being taken over by old imperial subjects in Asia and Africa.

Recent commentary in Canada, for example, has suggested that the Government of the United Kingdom (beyond its royal family) has largely lost interest in the Commonwealth. Yet there are at least some signs in the 2020s that the world’s largest democratic Government of India (as troubling as it has sometimes seemed under the Hindu nationalism of Prime Minister Narendra Modi?) may be taking on a new leadership role in the organization. And this is logical enough in the democratic sense that the population of India (1.4 billion) now accounts for more than half the 2.5 billion people in the “56 independent and equal countries” of the mid 2020s Commonwealth.

As a matter of casual empiricism at least, it often seems that both the Commonwealth and La Francophonie are also increasingly staffed by Asians and Africans. A Commonwealth still led by the old colonial power of the United Kingdom may well have increasingly less and less interest for Canadians in the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s. But a Commonwealth increasingly led by the world’s largest democracy in India, and staffed largely by Asians and Africans, may have a more intriguing future for a Canada that aspires to look first (if not always last) to the 21st century global village.

Canada, the United States, Mexico and the Caribbean

in the Global Village

In various ways the late 20th century transformed Canada’s sense of itself in the wider world community — about which both Indigenous and “Settler” (and Indigenous settler) Canadians had received early intelligence through their involvement with the unforgivably imperialist but nonetheless quite global empire, on which the sun never dared to set. (And through the other European global empire which left Canada militarily in the 18th century, but still had its own denouement after the Second World War.)

Some changes in the world economy that began to surface in the 1980s pointed to new virtues of regional alliances, in navigating the increasingly rocky waters of international trade. And, to start with, regionally Canada had lived next door to the United States of America ever since the birth of the United States in the late 18th century.

Even francophone Quebec was and still is part of the anglophone and increasingly global North American culture that owed so much to the increasingly diverse society of the USA. And for the seven decades from the end of the Second World War in 1945 to (say) 2015, the United States was at the top of various global institutions — from Wall Street and the United Nations in New York, to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC, and Hollywood and the high technology industry (and the Internet) in the Pacific state of California.

In the Canada-US “free trade” election of 1988 a majority of the electorate, Canada-wide, nonetheless voted for either the Liberals (32%) or New Democrats (20%). And both parties opposed what finally became the Canada-US “FTA” (Free Trade Agreement), that Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government in Canada had negotiated with Ronald Reagan’s Republican government in the United States.

In the 1988 Canadian election that was effectively a referendum on the proposed FTA, the Conservatives won a majority of the popular vote in only two provinces — Quebec (53%) and Alberta (52%). Elsewhere provincially the pro-FTA Conservative vote ranged from a high of 42% in Newfoundland to a low of 35% in BC.

Thanks to the sometimes bizarre workings of Canada’s traditional Westminster electoral system (with three but no more parties actually winning seats in 1988), 43% of the vote Canada-wide was still enough to give the Mulroney Conservatives 169 seats, in a 295-member House where 148 seats was a bare majority. The Canada-US FTA became the law of both lands in 1989. And (not for the last time) the minority of the voters in Quebec and Alberta led the majority in the rest of Canada!

******

Fortunately for national unity the main objection to the Mulroney Conservative FTA was political not economic. How long could Canada, with not much more than one tenth the population of the United States, survive in a relationship with the friendly giant next door all by itself?

The question was rendered null and void soon enough. Once the Canada-US FTA was working US enthusiasts in particular urged that Mexico be brought into a rising new North American Free Trade region.

Sheer geography means that Canada can never be as close to Mexico as the United States. In their own ways, however, Canadians could better understand at least the more abstract depths of the often cited words of Porfirio Díaz, President of Mexico, 1876, 1877–1880, 1884–1911 : “Poor Mexico, So Far From God, So Close to the United States.”

Some would say these same words described the Canada pursued by Liberals and New Democrats in the late 20th century and beyond, starting with “So Far From God.” In any case, as explained by the Government of Canada website in 2023 : “The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), signed by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, Mexican President Carlos Salinas, and U.S. President George H.W. Bush, came into effect on January 1, 1994. NAFTA has generated economic growth and rising standards of living for the people of all three member countries.”

By 1994 Jean Chretien’s Liberal government was in office, with finance minister Paul Martin. And this Liberal regime (if not many New Democrats in opposition?) was more friendly to a regional free trade agreement that also included Mexico. This was not such an obvious threat to Canada’s long-term political sovereignty. At least the burden of “So Close to the United States” could be shared.

Much much later, during the presidency of Donald Trump in the United States (2017–2021), NAFTA was renegotiated — in a way that was said to be more fair to the United States. From Canada’s point of view, very little changed. Canada remains committed to global free trade under multilateral agreements. But this commitment still begins with a primary regional trade agreement in North America.

******

There is one respect in which the current definition of “North America” in the old and the new NAFTA (with the latter sometimes known in Canada as CUSMA, for Canada United States Mexico Agreement) arguably leaves an important part of the modern region out.

That is the island sub-region of the Carribean Sea — already linked as the Caribbean Community or CARICOM : “twenty countries: fifteen Member States and five Associate Members … home to approximately sixteen million citizens … Indigenous Peoples, Africans, Indians, Europeans, Chinese, Portuguese and Javanese … multi-lingual … with English as the major language complemented by French and Dutch … as well as African and Asian expressions.”

The Canadian banks that expanded into the Caribbean in the early 20th century had become less enthusiastic about the region by the early 21st century. But starting especially in the 1960s many individuals especially from such newly independent anglophone Commonwealth Caribbean countries as Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago migrated to Canada. And Michaëlle Jean, a 10-year-old refugee from francophone Haiti in Quebec in 1968, ultimately served as Governor General of Canada, 2005–2010.

Including the Caribbean region in some future North American trade agreement involving the United States, Mexico, and Canada may not be an arrangement that altogether works for the Caribbean region. (And then the geographic region includes Cuba, with which Canada and Canadians have had more to do than the United States since the ultimate incarnation of Fidel Castro.) At the most fantastic end of regional speculation, a Canada whose formal constitution and informal day-to-day real life whole-heartedly and somewhat warmly included a francophone-majority Québec, in which the Québécois were securely and unambiguously “a nation within a united Canada,” might also have room for such parallel Caribbean nations as the Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica, or Saint Lucia.

******

It is not entirely an accident that the Canadian Marshall McLuhan coined the term “global village” in the 1960s. Some 60 years later, as noted above, the 2021 Census showed that “one in four Canadians … had a mother tongue other than English or French … Aside from English and French, Mandarin and Punjabi were the country’s most widely spoken languages.”

The two languages that now figure as “ the country’s most widely spoken” beyond English and French also draw attention to the two ancient civilizations of Asia alluded to by George Orwell, in a 1947 essay called “Toward European Unity.” (And 1947 coincidentally was also the year the first Canadian Citizenship Act took effect — and the year of the Letters Patent that effectively transferred George VI’s powers over Canada to the Governor General of Canada : a document signed by the Prime Minister of Canada, who by this point also appointed the Governor General.)

As Orwell wrote back then : “It may be that Europe is finished and that in the long run some better form of society will arise in India or China. But I believe that it is only in Europe, if anywhere, that democratic Socialism could be made a reality in short enough time to prevent the dropping of the atom bombs.”

Three-quarters of a century later humanity has managed to avoid the dropping of atom bombs, so far, beyond those that wrought such hideous tragedy in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the middle of the summer of 1945. And at least more democratic Socialism than many ardent capitalists would prefer has subsequently made its way in Europe and some parts of Asia (India, Australia, and New Zealand, for starters) and Africa (where the next great burst of human population growth is already in progress) and even North and South America.

To end on an upbeat note, “social democracy” may even grow somewhat more popular in the global village of the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s (along with some approximation of a more stable free-market capitalism?). Meanwhile, Canada today starts with its Indigenous peoples (who have among many other things given the country its name). It finally goes on to include people from virtually every corner of the world today.

Canada is not unique in this respect. Australia, a multicultural country in another intriguing vast and varied geography, is a related case. Europe itself is becoming more diverse — in such places as Italy, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Then there is the United States (blue and even red). And India is an ancient example of multiculturalism at work. Even so, and whatever else, in the midst of it all Canadians of the 2020s, 2030s, and 2040s are all of us children of the global village — on which the sun now never sets in a new, much deeper and more interesting way.

SOURCES

This is an initial dry-run at what will finally appear in a published hard-copy text, subject to further checking, correction, and editing. The order of the items here broadly matches the order of the text above. The online linkages reported are as of early Spring 2023.

Donald J. Savoie, Democracy in Canada: The Disintegration of Our Institutions. Montreal and Kingston : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019.

https://www.amazon.ca/Democracy-Canada-Disintegration-Our-Institutions/dp/0773559027

Phillip Buckner, Review of Democracy in Canada by Donald J. Savoie. British Journal of Canadian Studies, Volume 33, Number 2, 2021, pp. 270-271.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/806458

Martin Armstrong, “The State of Democracy : Global Democracy Index rates, by country/territory (2022),” statista, Feb 17, 2023.

https://www.statista.com/chart/18737/democracy-index-world-map/

Mickey Djuric, “Review of democratic processes needed as ministerial responsibility changes: experts,” The Canadian Press, April 9, 2023.

https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/review-of-democratic-processes-needed-as-ministerial-responsibility-changes-experts-1.6348178

Renewing the democratic constitutional odyssey …

very gradually

Canada, Justice Laws Website, Constitution Act, 1867. 30 & 31 Victoria, c. 3 (U.K.). “Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom:”

https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-1.html

Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution (With an Introduction by R.H.S. Crossman). London : Collins — Fontana Library, 1867, 1915, 1963, 1964.

https://www.amazon.ca/English-Constitution-Introduction-R-Crossman/dp/B001COLLTM

Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution. Second Edition 1873. McMaster University pdf file. Date unknown.

https://historyofeconomicthought.mcmaster.ca/bagehot/constitution.pdf

The English Constitution by Walter Bagehot. Project Gutenberg.

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/4351

The English Constitution. Walter Bagehot. Edited with an introduction and notes by Miles Taylor. Oxford World’s Classics : 1867, 2009.

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-english-constitution-9780199539017?cc=ca&lang=en&

Neal Ascherson, “Scribbles in a Storm” (Review of The Gun, the Ship and the Pen: Warfare, Constitutions and the Making of the Modern World by Linda Colley), London Review of Books, 1 April 2021, Vol. 43 No. 7.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n07/neal-ascherson/scribbles-in-a-storm

United States Senate, Constitution of the United States. “Written in 1787, ratified in 1788, and in operation since 1789, the United States Constitution is the world’s longest surviving written charter of government. Its first three words — ‘We The People; — affirm that the government of the United States exists to serve its citizens. The supremacy of the people through their elected representatives is recognized in Article I …”

https://www.senate.gov/civics/constitution_item/constitution.htm