Canadian flag to Parti Québécois government, 1963–1976

Dec 23rd, 2018 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage Now

Some would characterize the Nobel Peace Prize winner Lester “Mike” Pearson’s comparatively short prime ministerial career (1963–68) as the time when Canada’s long-incubating federal welfare state achieved its ultimate modern fruition. Others would allude to one of “the most influential commissions in Canadian history, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1963–69),” which “brought about sweeping changes to federal and provincial language policy.”

Yet for Mackenzie King’s nation-building legacy and the growth of modern Canadian democracy, Prime Minister Pearson’s ultimate contribution was almost certainly the maple leaf flag that would officially (and “legally”) become the symbol of Canada as an independent member state of the modern United Nations, on February 15, 1965.

Mackenzie King himself had tried two earlier gentle explorations of an independent Canadian flag — in the middle of the 1920s and then again in the middle of the 1940s. Neither had succeeded to anyone’s satisfaction. But King did bequeath some interim official status for the “red ensign,” with a British Union Jack in the top left hand corner (or canton) and a Canadian coat of arms in the fly. Various versions of this British red ensign had served as an unofficial Canadian flag of sorts since the late 19th century — much as British blue ensigns came to (and still) serve similar purposes in Canada’s fellow dominions of Australia and New Zealand.

Lester Pearson had already speculated about Canada’s future as a republic in the dark days after the fall of France in June 1940 (within earshot of his then fellow diplomat Charles Ritchie at any rate). But he did not exactly propose the red and white Canadian maple leaf flag that became a legal fact of life in February 1965 as a republican symbol. According to the historian J.L. Granatstein, it was his Suez Crisis days that finally convinced Pearson Canada must have a flag of its own.

As explained by a peacekeeping website today, “Egyptian President Nasser objected to Canadian troops for the UNEF peacekeeping force” Lester Pearson had invented, partly because “Canada’s flag, the Red Ensign” had “a British Union Jack in the corner.” And Britain was one of the contending parties that the force was meant to keep peaceful. On the purest Granatstein thesis, then and there Mike Pearson resolved that he would give Canada its own flag as an independent country, if and when he became prime minister. When this did happen in the election of April 8, 1963, that is what he proceeded to do.

(Albeit also on a wave of popular enthusiasm — as suggested by a 1958 opinion poll reporting that more than 80% of Canadians “wanted a national flag entirely different than that of any other nation.” The cause was supported as well by the Tommy Douglas New Democrats, who gave Pearson’s first Liberal minority government 1963–65 its majority in parliament. And, whatever else, the flag started to tell the world that the Canadian people ultimately ruled, in what the Constitution Act, 1982 would finally allude to as the “free and democratic society” in Canada today.)

La Révolution tranquille in Quebec (and the rest of Canada)

In one sense Canada in the 1960s and 1970s just followed larger trends in the increasingly discernible “global village” that Marshall McLuhan wrote about in The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964).

In other ways Canadian developments had crucial local roots. And much that was interesting and finally forward-looking — as well as sometimes annoying and worse — began in “La belle province” (the motto on Quebec automobile licence plates until 1978, when it was replaced by “Je me souviens”).

“La Révolution tranquille” (the Quiet Revolution) is customarily dated from the victory of Jean Lesage’s Quebec Liberal party in the June 22, 1960 provincial election — following the death of the right-wing Union Nationale leader Maurice Duplessis in 1959. But what the revolution finally led to in the middle of the 1970s could also be said to have begun with Duplessis’s invention of a distinctive Quebec flag in 1948. (And that arguably even served as an additional inspiration for Lester Pearson’s distinctive Canadian flag in 1965.)

The Quiet Revolution soon included a growing Quebec “sovereigntist” movement, culminating with the birth of the provincial Parti Québécois in 1968, led by the former Liberal quiet revolutionary René Lévesque. The movement was also inspired by the transformation of the global British empire that created the Republic of India in 1950, the west African independent state of Ghana in 1957, the independent Caribbean state of Trinidad and Tobago in 1962, and the independent east African state of Kenya in 1963. (To cite just a few examples.)

Meanwhile, the extremist revolutionary Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) established in 1963 was inspired in some degree by the Front de libération nationale (FLN), established in 1954 in the freedom-seeking French colony of Algeria. (See, eg, The Battle of Algiers — “a 1966 Italian-Algerian historical war film … based on events during the Algerian War [1954–62] against the French government in North Africa.”)

When André Siegfried — “the preeminent French geographer of his generation” (Canadian Encyclopedia) — published Le Canada. Les deux races. Problemes politiques contemporains in Paris in 1906, he believed that the global British empire would remain some form of essential political framework for both English-and-French-speaking Canada for a very long time ahead. But that was before the initial creative destruction of the First World War, and then the gradual dismantling of European empires everywhere that followed the end of the Second World War in 1945.

On the ultimate post-colonial trajectory, the October Crisis of 1970 in Canada began “with the kidnapping of James Cross, the British trade commissioner in Montréal,” by members of the FLQ. In its extremist revolutionary depths, it was the already deconstructing British empire that the Quebec sovereigntist movement most ardently yearned to escape from, not exactly the Canadian confederation of 1867.

Even René Lévesque’s parliamentary democratic Parti Québécois arm of the movement did not quite want “independence” for the Canadian province of Quebec. On the new PQ scenario what had finally become Canada’s largest province geographically, with a French-speaking majority, and longstanding French civil rather than English common law, wanted “sovereignty — and at the same time to maintain with Canada an economic association.” (And in the 1980s and 1990s it would become clear that for many sovereigntists the “association” had more than strictly economic sides, as an already long and deep “histoire canadienne” might suggest!)

* * * *

In the 1960s and 1970s the barest beginnings of parallel aspirations for liberation from the old British empire and what René Lévesque called the “colonized mind” also put down roots in the (predominantly) English-speaking rest of Canada outside Quebec. The new maple leaf flag of February 15, 1965 was just a leading edge.

(And in a related sidebar, Eamon de Valera, 81-year-old ceremonial president of a still rather new Irish Republic, visited Canada during the flag debate of 1964, in a “coda to an official visit to the United States.” He sympathized with Lester Pearson and advised : “To get a flag accepted, you have to have blood on it. You have to have waved it fighting somebody … You really ought to take your flag down to the American border –it’s not very far away — and get some of your friends on the other side to take some shots at it, and if you get somebody to be mildly wounded, that will make all the difference.” According to a much later report in the Montreal Gazette, “Pearson thought the old man was joking. Perhaps he was.”)

The rather elaborately celebrated centennial of the 1867 confederation on July 1, 1967 was a kind of booster for the embryonic Canadian patriotism of the new maple leaf flag. At the same time, the flag debate in the Canadian House of Commons in 1964 pitted the Pearson Liberals and the Douglas New Democrats, who supported the new flag, against the Diefenbaker Progressive Conservatives (outside Quebec), who felt the old Canadian red ensign with the British Union Jack in the canton was as good a flag as Canada needed.

Much of the English-speaking Canadian identity beyond francophone Quebec (and, some would similarly stress, the multicultural Canadian Métis, coast to coast to coast), was still focused on some hybrid “British American” heritage, rooted in what was still legally and constitutionally a creation of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, still known as the British North America Act, 1867.

Mitchell Sharp, who served in the Liberal cabinets of both Lester Pearson and his successor Pierre Trudeau, was a Canadian republican. As he later explained in a memoir, he strongly believed “that Canada should have its own head of state who is not shared by others” — while continuing “to model our system of government on that of Britain.” (As, eg, in the 1960s parliamentary democratic republics of India and Ireland.)

Sharp also noted in his memoir, published in 1994 : “My views on the monarchy were well-known to my colleagues in both the Pearson and Trudeau cabinets. They were also known to some others. So far, however, I have obviously failed to rally a significant following. One would think that my views would have appealed to French Canadians like Trudeau. Perhaps they did. But, he did not act on them.”

* * * *

One key ingredient in what the political scientist Frederick Vaughan would much later call Canada’s “reluctant republic,” born at last ever so quietly (and unofficially of course) in the 1960s, was the cold-war politics of the USA next door.

The first wave of Harold Innis’s friendly new American imperialism (“made plausible and attractive in part by the insistence that it is not imperialistic”) arose in the immediate wake of the Second World War. It had already drawn even Mackenzie King somewhat closer to the British monarchy in his last years, as a kind of cultural hedge against manifestly destined annexation at last by the rising new global empire that insisted it was not an empire, headquartered in Washington, DC.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 and then the US Congress’s August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (which led to major US involvement in Vietnam) stiffened the pressures from down south that both Diefenbaker and Pearson lived with. Even the Lester Pearson who insisted on an independent Canadian flag still sometimes found himself alluding positively to Canada’s traditional attachments to a Queen Elizabeth II still in her late 30s and early 40s, who lived in palaces across the seas.

Canada did not join the US military mission in Vietnam. (It provided a home away from home for draft-dodging refugees from the USA instead.) In April 1965 Prime Minister Pearson gave a speech at Temple University in Philadelphia, “suggesting a pause in the bombing of North Vietnam.” As explained by the historian Brendan Kelly, this “enraged United States President Lyndon B. Johnson, who in private the next day at Camp David strongly rebuked the Canadian prime minister.” (According to a more flamboyant legend, Johnson grabbed Pearson by his suit-coat lapels and shouted in his face : “You pissed on my carpet.”)

Meanwhile, as Alexander Brady had underlined in Democracy in the Dominions, even beyond the unique North American society of francophone Quebec, the emerging new and altogether independent Canada was a geographically vast country of several major regions. Moving east to west, there was Atlantic Canada (complicated in its own right with the addition of Newfoundland in 1949). Then there was the unique society in the second most populous province of Quebec, and then the most populous province of Ontario (a place of regions in its own right).

Then there were the three vast Prairie provinces of Western Canada, and then Canada’s Pacific Coast in British Columbia, increasingly just known as BC. (And then there were the still more predominantly Indigenous far northern territories, stretching all the way to the North Pole.)

Each region had its own ideas about independent Canadian identities. By the 1960s early post-colonial stirrings among First Nations, and increasingly diverse migrations from all over the emerging wider global village, were already starting to add further complications.

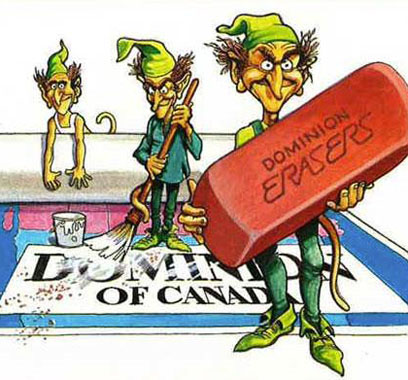

Yet in the midst of all this the new flag was not the only sign of a fading old first self-governing British dominion. For various inquiring minds, coast to coast to coast, something significant was quietly afoot, eg, in 1971, when the Dominion Bureau of Statistics in Ottawa was renamed Statistics Canada. (Here as elsewhere there is from the start a somewhat different journey in French — from Bureau fédéral de la statistique to Statistique Canada. And in all 10 provinces, as in the case of the flag again, at first some were for the change, and some were not.)

Economic development and the federal-provincial welfare state

There were economic nationalist sides to the new patriotism of the maple leaf flag (and the quiet resistence to the new imperialism next door).

Walter Gordon, who had chaired the Royal Commission on Canada’s Economic Prospects, with all its worries about growing foreign (and especially US) ownership in the Canadian economy, was Pearson’s Minister of Finance from 1963 to 1965. His “1963 budget proposal for a tax on takeovers of Canadian firms,” however, “was withdrawn under pressure, and his influence in Cabinet waned until his resignation after [the] general election of November 1965” (Canadian Encyclopedia).

The Pearson Liberals had clearly enough defeated the Diefenbaker Conservatives on April 8, 1963 — in both popular vote percentage and number of seats in the Canadian House of Commons. But (especially with four active parties) they had not quite managed a governing majority of seats. One exotic rumour claimed six Social Credit MPs had signed an agreement to vote with the new Pearson government. But this was denied by both sides. The 17 New Democrat MPs would support the government’s progressive legislation in any case.

Yet life would still have been easier if the Liberals had a majority in the House. And soon enough the new flag and pioneering pension legislation renewed the old natural governing party’s faith (or, others would say, arrogance). By the late summer of 1965 finance minister Walter Gordon (not yet bereft of all influence), progressive policy guru Tom Kent, and political rainmaker Keith Davey were urging Prime Minister Pearson to call a fresh election. They were confident the Liberals could now win a majority. After a cabinet meeting with only one dissenting voice, the election was called for November 8, 1965.

During the campaign Lester Pearson enthused : “We Canadians … have built out of this northern part of the continent one country — from ocean to ocean — from the southern border to the Arctic sea … And we are going to keep it Canadian … a strong, a separate state that shares a continent and counts in the world.”

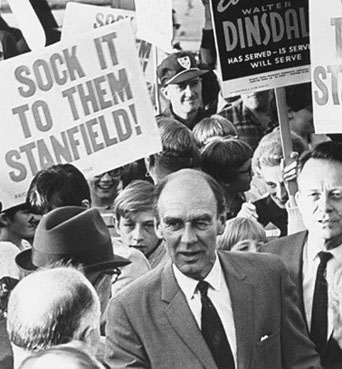

The words moved some Canadians. Yet, as gifted as he was in other ways, Mike Pearson was no retail politician. Meanwhile, the new leader of the Social Credit party in Quebec, Réal Caouette, wildly “charged that the government had made a commitment to conscript 100,000 Canadians for Vietnam.” Some in John Diefenbaker’s own party were unhappy that he was still Progressive Conservative leader. But he was also still a born campaigner. In 1965 he was the prairie populist star of the last big whistle-stop railway tour in Canadian political history. In the end the Liberals managed to win only two more seats — another two seats short of even a bare majority in the House. The New Democrats had nonetheless won four new seats. And the government’s reform agenda remained intact.

* * * *

Walter Gordon’s aggressive economic nationalism faded from the Ottawa mainstream after the 1965 election, under particular pressure from the Canada-US Auto Pact in Ontario, and the growth of the Alberta oil and gas industry (which “more than tripled between 1960 and 1973”).

The 1965 Auto Pact was another response to the transformation of the global British empire after the Second World War. Despite its role in regionalist legends, the domestic market in Canada was never large enough to sustain the “Canadian-American” manufacturing sector that developed in central Canada after the First World War. In the 1920s Toronto newspaper ads for General Motors of Canada had explained that exports to the global British empire “swell … production to a point far beyond the possible demands of our home market alone.”

As the heyday of all European empires waned in the 1960s, the Auto Pact’s effective integration of automobile production in the United States and Canada compensated for falling British empire markets with the vast and rising, world-leading American domestic market right next door.

Strictly Canadian financial interests similarly fell short in the growth of the rapidly expanding oil and gas industry in Alberta — a logical enough “Canadian-American” extension of the booming 1960s US oil industry focused on Texas. And here, as in manufacturing back east, US “foreign investment” was shaped by Canadian public policy.

The Diefenbaker government had established a “National Oil Policy” in 1961. Consumers east of the Ottawa River between Ontario and Quebec “would be supplied with oil products made from imported crude.” Consumers west of the river “would rely solely on Canadian-produced oil.” As later explained by André Plourde at the University of Alberta : “By curbing imports into Ontario,” the policy “acted to boost the average price of Canadian-produced oil,” and strengthened “access to markets in Ontario and the United States. As a result, oil production grew sharply.”

Then in September 1973 — “a few weeks before the onset of the Yom Kippur War that would arguably lead to the first world oil price shock” — Pierre Trudeau’s federal government “announced its intention to exercise its constitutional powers, first to curb oil and gas exports, and second to regulate the prices of these commodities sold on markets outside of the provinces of production.” The Trudeau government had “also announced its intention to create a national petroleum company.” It was up and running by 1975, under the brand name Petro Canada.

* * * *

Meanwhile, earlier economic nationalist currents took on their own new forms. In 1970 Walter Gordon and three associates founded the Committee for an Independent Canada. In the same year the McGill University economist Kari Levitt — daughter of the Viennese journalist Karl Polanyi, whose 1944 book The Great Transformation argued that “the market society is not a naturally occurring phenomenon” — published Silent Surrender : The Multinational Corporation in Canada.

Silent Surrender predicted “that the ultimate consequence of relinquishing control of the Canadian economy to United States business interests would be political disintegration through the balkanization of the country and its eventual piecemeal absorption into the American imperial system.” In response to all such criticism Pierre Trudeau’s Liberal federal government established a Canada Development Corporation (CDC) in 1971 (“to buy back the country” some said), and then a Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA) in 1973.

And then again, even in the 1970s there was Canadian “foreign investment” in the United States, as well as US foreign investment in Canada. Four decades later the CN Rail successor to Canadian National Railways had become “the only transcontinental rail network in North America,” stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific up north, and all the way down the Mississippi valley to the Gulf of Mexico in the south. (An echo of the old French-American empire at its mid-18th century height!)

Still later again when the US Republican Senator from Arizona Jeff Flake urged the benefits of close Canada-US economic ties on his fellow citizens in 2018, he noted that “Canadian companies operating in the United States directly employ more than 500,000 Americans.”

* * * *

In 1968 the Peter C. Newman who had reported on the Diefenbaker regime with Renegade in Power in 1963 published a parallel study of the subsequent five years, aptly called The Distemper of Our Times.

Without thinking too much about it, Canada like many other parts of an emerging new global village was starting to change in some profound ways. And neither the old-school populist orator John Diefenbaker nor the postwar UN intellectual and bow-tie bureaucrat, Lester “Mike” Pearson, seemed even inexactly suited to the 1960s.

Yet several decades later, in the early 21st century, when a Canadian policy journal “asked historians, political scientists, public service mandarins and journalists to choose the best prime minister of the last half of the twentieth century, Pearson easily took first place.”

Beyond the strictly symbolic maple leaf flag, a big part of this eminence flows from Lester Pearson’s role in the consummation of a modern federal-provincial welfare state in Canada, over his almost exactly five short years as prime minister (22 April 1963–20 April 1968).

One key ingredient was a Canada Pension Plan (and a largely identical but separate Quebec Pension Plan), which took effect in 1966. This built on almost four decades of public policy development, starting with the Mackenzie King regime’s Old Age Pension of 1927, which had “provided the elderly poor with some relief.”

Along the way the process included a 1951 amendment to the 1867 BNA Act (still passed by the UK parliament, at the request of the Canadian parliament). It allowed “the federal government to pass the Old Age Security Act.” This took effect in January 1952, and “established a federally funded pension for all men and women 70 years of age and over.”

Even in the 1950s, however, “retirement still meant a drastically reduced standard of living for many people.” By the 1960s there was “growing public and political support for a universal, employment-based pension plan that would be portable from job to job.”

As explained by the Canadian Museum of History, the “provinces agreed to another Constitutional amendment to extend federal government powers beyond legislation that applied only to old age.”

And then “the contributory Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Quebec Pension Plan (QPP) were established in 1966.” Recipients “received benefits based on the amount they contributed” — and on when they chose to start receiving benefits, from 60 to70 years old today.

(A notable wrinkle in the scheme was much later explained by policy analysts R. Kent Weaver and Daniel Béland : “Successive Quebec [provincial] governments used pension surpluses” from the QPP “to feed the newly created Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, an institutional asset manager that served as a key tool for provincial economic development in pursuit of the statist project of the Quiet Revolution.”)

* * * *

The Pearson government also carried on with the broadening of Canadian immigration policy begun by John Diefenbaker’s first Canadian woman cabinet minister, Ellen Fairclough. By 1967 all forms of cultural, ethnic, geographic, or racial requirements for new immigrants were dropped, as Canada adopted the culturally neutral points-based system for assessing immigration applicants still in use today.

Back inside the home and native land, the Canada Student Loan Plan that began in 1964 provided federal help for post-secondary education across the country. And the Canada Assistance Plan that began in 1966 boosted federal financial support for growing provincial social welfare programs.

The ultimate ingredient of the Canadian federal-provincial welfare state that crystallized in the last half of the 1960s was a public health care system, operated by the provinces (constitutionally responsible under the 1867 BNA Act) but funded in part by Ottawa.

The federal government initially paid “about half of Medicare costs in any province with insurance plans that met the criteria of being universal, publicly administered, portable and comprehensive.” The starting date for the federal program was July 1, 1968. By “1971 all provinces had established plans which met the criteria.”

Over the next several decades the federal share of provincial health care expenditures would not stay at “about half.” (It ranged around only 20% in the early 21st century.) Canadian public health care had similarly been pioneered in the early 1960s by the “first socialist government in North America,” in the province of Saskatchewan shaped for 17 long years by Premier Tommy Douglas (1944–1961).

At the other end of the ideological spectrum, it was the Diefenbaker Progressive Conservative government that appointed the Hall Commission, to study medical insurance in Canada in 1961. As in the more general case, the federal-provincial welfare or service state that crystallized under the Pearson Liberals in the later 1960s had deeper nonpartisan roots.

First incarnation of Pierre Elliott Trudeau and Quebec provincial election of 1976

One of Lester Pearson’s further contributions to the growth of an independent Canadian democracy did include his intellectual grasp of the changing real world in francophone Quebec — and the fresh political relevance of the stubborn “French fact” in Canada at large.

Pearson’s high-minded virtues here had practical political sides as well. And they helped persuade “Three Wise Men” from Quebec to run (and win seats) for the Liberals in the 1965 federal election : Jean Marchand, Gérard Pelletier, and Pierre Elliott Trudeau (also known as “les trois colombes” or three doves in French).

The alphabetical third of the wise men would have by far the greatest impact. His unique background played a part. In the new automobile age after the First World War Pierre Trudeau’s unusual French Canadian businessman father had built a chain of gas and repair stations in Quebec. Selling to larger corporate interests in the depression depths of 1932 led to a subsequent career as an investor in Canadian mines, a major amusement park, and the Montreal Royals “Triple A” baseball team.

Even when he died unusually early, at 48, the entrepreneurial Charles-Émile Trudeau had left his wife and three children financially independent. His elder son Pierre Elliott Trudeau (whose mother Grace Elliott had an “English” or more exactly Scottish father and a “French” mother) was only 15. Yet he thought: “all of a sudden, I was more or less the head of a family … it seemed to me that I had to take over.”

More than 30 years later, at “”the most chaotic, confusing, and emotionally draining convention in Canadian political history”(Globe and Mail) — held on April 6, 1968 at a still quite new Ottawa Civic Centre — Pierre Elliott Trudeau became leader of the Liberal Party of Canada, “with the support of 51% [of the] delegates on the fourth ballot.”

From the start Pierre Trudeau was a controversial Liberal leader and head of government. Despite his father’s impressive career, the strongly pro-business right wing of his own party never liked the first Prime Minister Trudeau. The feeling was widely enough shared, especially among conservatives on the prairies and sovereigntists in his own province. Yet in his late 40s he was the unusual left-wing intellectual son of a right-wing francophone businessman. He was also an athletic lawyer and urbane, well-travelled native of Montreal who seemed to fit the 1960s like a glove. In strategic parts of the body politic “Trudeaumania” seized the electorate.

Lester Pearson resigned as prime minister. The new Liberal leader formed a new government, and called an election for June 25, 1968. It was the Canadian democratic moment when airplanes and TV finally replaced the old railways and newspapers in communicating with voters.

On election night the Progressive Conservatives, now led by the dour Robert Stanfield from a wealthy Nova Scotia family of clothing manufacturers, took at least the plurality of the popular vote in all four Atlantic provinces, and in Saskatchewan and Alberta. The Trudeau Liberals did the same or better in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and BC (which all together had more than three-quarters of the Canada-wide population).

The Liberals’ new charismatic leader (now treated by crowds “like a Beatle,” his sister was astonished to see) did at that moment seem especially suited to his time and place. At last Canada’s self-appointed old natural governing party won another majority government — with 45%+ of the cross-country popular vote and more than 20 seats to spare.

* * * *

The Pierre Trudeau Liberals’ first four years in office, 1968–1972, add up to a puzzling mix of achievement and confusion — perhaps not unlike the story of Marshall McLuhan’s wider global village during the same period.

To start with, as his biographer John English has explained, one of the new Liberal leader’s early boasts was that he “brought French power to Canada — and he remained immensely proud of this achievement, even though it later became a political burden.” Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s decision to move into George-Étienne Cartier’s old confederation-era office rather than John A. Macdonald’s signaled his initial passion on this issue.

Yet here as elsewhere, much of what Trudeau brought to fruition had been started by Lester Pearson. The Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism began its work in 1963 under Pearson’s government. The Official Languages Act that made the Canadian federal government “officially bilingual” took effect under Trudeau in September 1969.

(Section 133 of the British North America Act, 1867 had long provided for the use of both English and French in the federal parliament at Ottawa and the provincial legislature of Quebec. The 1969 Act further provided that all Canadians had a right to federal services in both languages, and that both English and French were equal as languages of work within the federal public service, in designated regions of the country where both languages were in significant popular use. New Brunswick, with its large Acadian population, also passed legislation making it the only officially bilingual province in 1969.)

Bilingualism, however, was one thing. Pierre Trudeau (flawlessly bilingual himself in both languages) was less enthused about the concept of English-French “biculturalism” in the 1963 Commission’s mandate. He was more interested in making all of Canada more hospitable to the French language, than he was in making Quebec a place where French was as dominant as English was in the rest of the country.

The growing numbers of old and new Canadian citizens whose increasingly diverse old-world backgrounds were neither French nor English were also frequent Liberal supporters in elections. In October 1971 Prime Minister Trudeau announced that the federal government was adopting “multiculturalism” as official policy. Ottawa would be officially bilingual and multicultural, not bilingual and bicultural.

This “official multicultural” policy — along with the altogether race-and-culture-blind immigration policy the federal government finally adopted in 1967 (under another wise man from Quebec, citizenship and immigration minister Jean Marchand) — would have profound implications over the next several decades. At the same time, and here as elsewhere again, Pierre Trudeau at his best was more of a catalyst for constructive but only gradually evolving new policy directions, than a successful inventor of well-conceived new federal programs promulgated from the top down.

* * * *

A 1969 White Paper on Indigenous issues (“formally known as the ‘Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy, 1969’”) was another case in point. It proposed at last abandoning the 1876 Indian Act with its “special status” for First Nations individuals still living on reserves (including the appalling residential schools), and assimilating Indigenous peoples into the same mainstream society as all other Canadian citizens.

This White Paper was formally retracted in 1971, when it became clear that a rising new generation of First Nations leaders passionately opposed it. Trudeau and his Liberal party ultimately made a beginning on a different kind of Indigenous policy, in the Constitution Act, 1982 and far beyond.

An earlier incarnation of Trudeau himself — as Lester Pearson’s attorney general — had more resolutely begun to liberalize Canada’s abortion, divorce, and same-sex relations law. (“The state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation.”) This finally found its way into the Criminal Code in 1969. Pierre Trudeau’s Canada also began negotiations with the People’s Republic of China” in 1968. And this led to the establishment of diplomatic relations with Chairman Mao Zedong on October 13, 1970.

By the time relations with Mao’s China had been established, the October Crisis that began with the extreme Quebec sovereigntist FLQ’s kidnapping of the British trade commissioner in Montreal, on October 5, was well underway. It would reach its nadir with the FLQ’s murder of Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte on October 17. Prime Minister Trudeau had already invoked the (unusually harsh) emergency War Measures Act on October 16, in response to what some Quebec and Ottawa politicians saw as a state of apprehended insurrection in la belle province.

Canadian troops briefly appeared on the streets of Ottawa and Montreal, and some 465 reputed sovereigntist activists were arrested and held without charge. Civil libertarians across the country attacked the prime minister for “using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut” (Tommy Douglas). But Trudeau’s steely action (“just watch me,” he told a critical TV reporter) did soon enough restore law and order. And it proved popular in all regions of the country in a December 1970 Gallup Poll.

Then, having tamed the apprehended insurrection in Quebec, on March 4, 1971 the 52-year-old Pierre Trudeau, to this point a bachelor previously (and/or subsequently) involved with the celebrated likes of Liona Boyd, Kim Cattrall, Gale Garnett, Margot Kidder, and Barbra Streisand (and various other beautiful francophones and anglophones), married the 23-year-old Margaret Sinclair at St. Stephen’s Roman Catholic church in North Vancouver. Ms. Sinclair was the attractive daughter of James Sinclair, a veteran BC Liberal and former Minister of Fisheries in Louis St. Laurent’s last government. On December 25, 1971 the spring-and-autumn couple welcomed the first of three sons, Justin Pierre James Trudeau (who would himself become prime minister of Canada some 44 years later!).

* * * *

A federal-provincial Constitutional Conference Pierre Trudeau convened in Victoria, BC, June 14–16, 1971 was less immediately successful — and points more clearly to new troubles in the 1972 election.

The conference’s great failure was that Quebec Liberal Premier Robert Bourassa, after first seeming to agree to an otherwise unanimously supported federal-provincial deal for at last “patriating” the 1867 British North America Act from the United Kingdom, finally disagreed after he returned home to find scant support among his advisors in Quebec City. Trudeau remained angry for some time. The meeting in Victoria nonetheless proved a rehearsal for what, just over a decade later, would become his most compelling legacy to his home and native land in the Constitution Act, 1982 (with its Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms).

The 1971 Victoria Conference — along with such allied new directions as official bilingualism and multiculturalism and the transformation of the Dominion Bureau of Statistics into Statistics Canada — did help convince some conservative (and other) admirers of the 1867 confederation that Pierre Elliott Trudeau intended to abolish its traditional attachment to the British monarchy, and turn Canada into a republic.

What some (realistically enough?) saw as an “anti-British” mood in the early Trudeau governing ethos had already raised fears of this sort. In response a former administrative assistant to former Progressive Conservative leader John Diefenbaker had started a non-governmental organization called The Monarchist League of Canada in 1970. (And over the next several decades it would develop some skill in persuading various receptive audiences that Canada’s “constitutional monarchy,” clearly written down in the 1867 BNA Act, continued to have certain advantages.)

In fact (and as is typically the case), the already almost entirely symbolic role of the monarchy in the modern Canadian parliamentary democracy that adopted its own independent flag in 1965 was not an issue in the federal election Pierre Trudeau called for October 30, 1972.

Yet other innovations of his first Liberal government were not immediately popular in many parts of the country — from official bilingualism on. The long postwar quarter-century of buoyant economic growth in places like Canada was also approaching less promising directions, as signaled by Richard Nixon’s cancellation of the US commitment to stabilize the price of gold at $35 an once in August 1971.

The Trudeau Liberals campaigned in 1972 on the somewhat puzzling slogan “The Land Is Strong.” But this time the number-of-seats result between the Liberals and Robert Stanfield’s Conservatives was so close that it wasn’t clear just who had “won” on election night. The next morning (with Halloween scheduled for that evening) it was clear the Liberals had 109 seats with more than 38% of the cross-country popular vote. The Conservatives had 107 seats with 35% of the vote.

Meanwhile the federal Social Credit party under Réal Caouette took 15 seats in Quebec. The New Democrats under the new leadership of David Lewis — running against what he memorably characterized as “corporate welfare bums” — won a record 31 seats with almost 18% of the cross-Canada vote. And the Trudeau Liberals remained in office for the next 20 months, under what might be characterized as a de facto or informal “coalition” or at least co-operation agreement with David Lewis’s NDP.

* * * *

Dependence on New Democrat support to pass legislation in the Canadian House of Commons did push Pierre Trudeau’s government somewhat to the left. And both the Foreign Investment Review Agency (FIRA) of 1973, and what finally became (the at first publicly owned) Petro Canada in 1975, owed something to the brief but potent burst of left-wing economic nationalism that de facto partnership with the Lewis New Democrats brought to the Trudeau Liberal government after the 1972 election.

Neither FIRA nor Petro Canada, however, would prove strong and enduring monuments to their causes over the mid to longer term. (The US financial weekly Barron’s, after initially attacking FIRA, ultimately explained how the only business enterprise “that wouldn’t be welcome in Canada is Murder Inc.”) New more troubling economic circumstances signaled by the 1971 end to a US-guaranteed price of gold, and then by the oil price shock of 1973, similarly pushed Canada’s federal Department of Finance in more conservative directions.

Pierre Trudeau’s polling numbers had been increasing in any case. If an economic recession was coming, it could be wise to call an election before it arrived. Fortuitously, to test finance minister John Turner’s continuing progressive resolve, David Lewis prepared what he called a “shopping list” of items for the May 1974 budget. Turner’s budget was judged not sufficiently forthcoming. And on May 8 the Lewis New Democrats voted with the Stanfield Conservatives and the Caouette Social Credit Party to bring the Liberal minority government down.

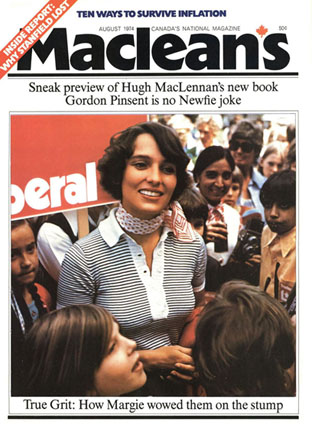

A fresh election was called for July 8, 1974. John English’s biography quietly suggests that Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s young wife Margaret, already pregnant with her second son, had something to do with the resulting Liberal majority government — 141 seats (eight more than a bare majority), earned with just over 43% of the cross-country popular vote. Margaret Trudeau insisted on joining the 1974 campaign, and she helped humanize the sometimes remote and arrogant first-term prime minister of 1972 in the eyes of many voters. (Meanwhile the Lewis New Democrats lost 15 of the 31 seats they had won in 1972 — helping to create a party tradition of scepticism about co-operating with Liberals.)

* * * *

In 1969 Pierre Trudeau had told the Washington Press Club that for Canada living next door to the United States was “in some ways like sleeping with an elephant. No matter how friendly … one is affected by every twitch and grunt.” On August 9, 1974 — just a month after the 1974 Canadian election — Richard Nixon resigned as American president, to avoid impeachment over the Watergate scandal. And this at least metaphorically signalled a new sea of troubles ahead for Canada too.

To start with, voter turnout in 1974 was only 71.0%, down by 5.7 % from 1972. In fact, the highest rates of turnout in the history of the 1867 confederation had already been reached in 1958, 1962, and 1963, at just under 80%. Turnout rose again to 75% in the elections of 1979, 1984, and 1988. But with these exceptions it would remain below 70% down to the present (with an all-time low of less than 59% in 2008). As in other places, mass attachments to Canada’s growing democracy were weakening.

The 1974 election also confirmed that democratic support for the Trudeau Liberals had somewhat ominous regional concentrations. They were strong in Ontario and Quebec, the francophone-dominated northern New Brunswick, and (sometimes) urban BC, but weak elsewhere. The 1973 oil price shock induced by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries also helped fuel what would become a long quarrel between Ottawa and the provincial government of Alberta over oil and gas policy. And a new more diffuse sense of (arguably quite deeply rooted) “western alienation,” beyond the Lake of the Woods on the Ontario-Manitoba border, was a counterpoint to the rising sovereigntist movement in Quebec.

More broadly, a new age of “stagflation” — inflation or rising prices and stagnant economic growth or employment — “was universal among the major economies during the period 1973 to 1982.” In Canada it would soon enough raise the thorny issue of wage and price controls. The Trudeau Liberals had opposed them in the 1974 election, and then (in new conditions) imposed them for a three-year period in the Anti-Inflation Act of 1975 (with wage guidelines binding on firms of 500 or more employees).

To at least try to promote economic growth, the Trudeau Liberals’ notion of a “Third Option” to Canada’s traditional trading ties with the British empire and the United States led to a “contractual link” with the 19-year-old European Economic Community. Pierre Trudeau had spent considerable time travelling in Europe to raise support for this agreement, which took effect on October 1, 1976. Yet while his father may have been a Canadian businessman who would have taken bold advantage of such a Canada-Europe linkage in the 1920s, there were not enough immediate successors in the 1970s to seriously boost the Canadian economy. Trudeau himself seems to have become somewhat intellectually bemused by the (no doubt often conflicting) opinions he was hearing from a variety of economic (and business) advisors in the middle of the 1970s. To add to his public policy burdens, in his private life the (almost inevitable?) strains of his marriage to a much younger woman were beginning to show as well. (As biographer John English would later explain : “In Margaret’s own words, ‘my rebellion started in 1974′.”)

Finally, on November 15, 1976 René Lévesque’s sovereigntist Parti Québécois took many in the rest of the country for a big surprise, and won 71 of 110 seats in the Quebec provincial legislature. (Which had already been renamed the National Assembly or Assemblée nationale du Québec, after the Assemblée nationale in France, in 1968.)

The chain-smoking M. Lévesque formed his first provincial government of Quebec on November 25, 1976. He had promised to hold a referendum on his party’s concept of “sovereignty-association” before the end of his first term. And this set the stage for what was at least widely imagined to be the possible break-up of the 1867 confederation, whose 100th anniversary had been celebrated with such enthusiasm (in some places at least) only nine years before. (Although those who focused on the 41.4% of the province-wide popular vote, that had given the PQ its 71 seats in the 1976 election, would in fact have a vaguely reassuring benchmark for just how well the referendum would finally do in 1980!)

From

Children of the Global Village :

Democracy in Canada Since 1497

Randall White

eastendbooks 2024

(For background on the larger work-in-progress of which this is a part, see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic.)