Arduous Destiny : Canada’s alternative to the Great Barbecue, 1873-1896

Mar 8th, 2017 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage Now

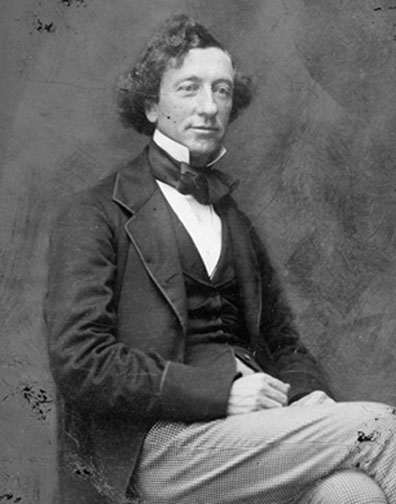

The Dominion of Canada might have evolved in a somewhat less British imperial direction over the last three decades of the 19th century, if French Canada had discovered some worthy successor to George-Étienne Cartier.

The closest approximation was probably Hector-Louis Langevin, after whom the Ottawa building (“Block”) that houses the 21st century Prime Minister’s Office in Canada is named (or at least was once).

Yet Cartier had been four months older than John A. Macdonald. Langevin was 11-and-a-half years younger. He became Macdonald’s “Quebec lieutenant.” But he lacked Cartier’s genial connections to influential French Canadians — and ordinary francophone voters.

Langevin’s early role in the Pacific Scandal also returned to haunt his later life as minister of public works. According to Andrée Désilets and Julia Skikavich, he was “driven out of Cabinet in 1891 amid accusations of corruption in his department.”

Though “later exonerated,” he languished on the back benches “until he retired from politics in 1896.” His fate was “seen as a disgraceful end to his long political career. It left Langevin devastated, and he hid from the public arena until his death in June 1906.”

(Then finally, in 2017 the Assembly of First Nations urged that Hector-Louis Langevin was a “key architect” of the “Indian residential school system” — a justly despised touchstone for the failings of Canadian First Nations policy in the 19th and 20th centuries. And AFN National Chief Perry Bellegarde argued that the name of the Langevin Block in the 21st century should be changed — which was done when the building was renamed the “Office of the Prime Minister and Privy Council” on June 21.)

* * * *

Back in the more immediate wake of the Pacific Scandal, both Hector-Louis Langevin and John A. Macdonald returned to power in 1878.

The Mackenzie Liberal government which began late in 1873 had shown that the politicians who led the early democratic struggle for responsible government in the provinces were not quite ready for the wider Canadian federal experiment. Alexander Mackenzie’s almost five years in office nonetheless set down both solid and some dubious groundwork for the federal Liberal Party and the broader government of Canada.

Not long after they formed a government in November 1873 Mackenzie and his colleagues held a fresh general election. They tried to ensure informally that all local riding contests would be held on a single day, Thursday, January 22, 1874. The scheme did not quite work. But “the government saw to it that most Canadians went to the polls within a few days of each other in later January or early February” (J. Murray Beck). The “Mackenzie Liberals” trounced the “Macdonald Conservatives,” on the back of the Pacific Scandal. They won any of 129, 133, or 138 of 206 seats in the Canadian House of Commons of the day (depending on just how their supporters were counted, in a less mindlessly partisan age).

The Mackenzie government has two important acts to its credit in the political history of Canada today. The first is electoral reform legislation that began a long post-confederation process of expanding Canadian democracy. The Elections Act of 1874, drafted after the 1874 election by Mackenzie’s first justice minister, the Quebec Rouge A.A. Dorion, prescribed formally that “general elections were to be held on the same day in all constituencies except Manitoba, British Columbia, and the more distant parts of Ontario and Quebec” (P.B. Waite). It also established a secret ballot (and decreed that “bars were to be closed on polling day”).

The second important act was the creation of a Supreme Court of Canada. This was a subject on which the Liberal Toronto lawyer Edward Blake had long pressed John A. Macdonald, who finally tabled a Supreme Court bill in 1869. Cartier, Langevin, and others opposed the bill, because “only two of the proposed seven judges would be French Canadian,” and able to deal with the French civil law in Quebec (as opposed to English common law everywhere else — since the Quebec Act of 1774).

Mackenzie’s second justice minister, Télesphore Fournier, managed to get a Supreme Court with two out of six judges from Quebec accepted by parliament in 1875. (In the early 21st century three of nine positions on the Supreme Court of Canada must still be held by members of the bar or superior judiciary of Quebec.)

Though the Supreme Court was established less than a decade after confederation in 1867, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom (JCPC) would remain the highest court of appeal in Canada until 1949. Urged on by Edward Blake and other early “Canada First” enthusiasts, Aemilius Irving and Rodolphe Laflamme had moved an amendment to Fournier’s 1875 legislation that would have sharply limited Canadian appeals to the JCPC from the start. But this was opposed by Lord Cairns, an important colleague of the UK “Red Tory” prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. As explained by Mackenzie biographer Ben Forster : “Disappointingly, the amendment became inoperative.”

Alexander Mackenzie’s first Liberal government of Canada also has one great dark blot on its record. In 1876 the Liberal-dominated Canadian House of Commons passed “An Act to amend and consolidate the laws respecting Indians.” This was the original “Indian Act” which even with many subsequent amendments remains a profound if also hard-to-altogether-escape source of trouble today.

The 1876 Act was “a consolidation of previous colonial ordinances that aimed to eradicate First Nations culture in favour of assimilation,” into a new settler society with still quite European habits. (And Hector-Louis Langevin played a role in trying to further this objective when he served as John A. Macdonald’s Secretary of State for the Provinces in the 1880s.) It would be another 54 years before Harold Innis wrote : “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions,” in the conclusion to The Fur Trade in Canada. It would be another 52 years again before section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 prescribed that the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.”

The most forward-looking side of Alexander Mackenzie’s government was the election of a thirty-something Henri Charles Wilfrid Laurier as Liberal MP for Quebec East in the 1874 election — and then the young Laurier’s ultimate elevation to Mackenzie’s cabinet as Minister of Inland Revenue in 1877. It would be another two long decades before Wilfrid Laurier officially began the 20th century story of the Liberals as “Canada’s natural governing party.” But a start had been made, between the first and second editions of John A. Macdonald’s governing Conservatives.

* * * *

The greatest failure of the 1873–1878 Liberal government, on some accounts, was its glacial progress on the commitment to British Columbia for a transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway. Part of the blame could be laid at the door of the Financial Panic of 1873, and the “first global depression brought about by industrial capitalism” that followed. But the penny-pinching agrarian democratic principles of Alexander Mackenzie and his Canadian Grit colleagues played a role as well.

As the Mackenzie biographer Ben Forster points out, more than 2,500 miles of track were actually added to Canadian railways between 1874 and 1879. This expansion, however, “was largely the result of the completion of the government-financed Intercolonial Railway, under engineer Sandford Fleming, and the construction of track under government contract in Manitoba and between that province and Lake Superior.” (The Intercolonial had been mandated by the original 1867 confederation deal, to connect the old Canada East with the Maritime Provinces.)

By the time John A. Macdonald returned to office, in a secret-ballot election (mostly) held on the single day of Tuesday, September 17, 1878, what US historians have called “the Long Depression, 1873–1878” had largely run its course. In more optimistic times Macdonald and his colleagues were able to inspire an initially government-befriended private enterprise. And it would take the track all the way from Montreal to the Pacific at 9:22 AM on Saturday, November 7, 1885, in Craigellachie, BC.

In the early 1970s, a century after it all began, the media impresario and popular historian Pierre Berton published his two-volume work on the origins of the Canadian Pacific Railway — The National Dream, 1871–1881 (1970) and The Last Spike, 1881–1885 (1971).

A one-volume version of the project called The National Dream / The Last Spike appeared in 1974. An Anchor Canada edition of The National Dream : The Great Railway, 1871—1881 was published in 2001, just a few years before Pierre Berton, born in the Yukon and seasoned in BC on the Pacific Coast, “passed away in Toronto on November 30, 2004.”

It may be that Canada in the 21st century has grown too remote from the haunting rhythms of the age of steam (and other things) to altogether embrace the early history of the CPR as a crucial nation-building adventure. (What about Air Canada, eg, or the Trans Canada Highway? Or as a US critic of Mr. Berton’s first volume rather darkly wondered : “What kind of country has a railway for its national dream?”)

At the same time, Pierre Berton was finally alluding to something larger than the railway age in the last half of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. Harold Innis’s first book, based on his University of Chicago PhD thesis and published in 1923 (when Pierre Berton was three years old), was A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The CPR had opened Innis’s eyes to the northern geographic unity mobilized by the first Canadian resource economy of the transcontinental fur trade.

On some similar trajectory (albeit at the very back of the imagination of the time), it was the CPR’s late 19th century revival of the late 18th and early 19th century golden age of the North West Company — “the forerunner of confederation … built on the work of the French voyageur, the contributions of the Indian … and the organizing ability of Anglo-American merchants” — that gave the first railway to the Pacific in Canada a mildly more exotic mantle than the earlier transcontinental railways to the south, in the much more populous United States.

The second volume of Pierre Berton’s CPR history, The Last Spike, covering “the construction phase between 1881 and 1885,” also underlines how, at this point in Canadian time, it was John A. Macdonald’s British imperialist Tories who had the deepest attachments to the old wilderness romance of the first resource economy, A Mari Usque ad Mare. (And this was partly because, as Harold Innis wrote on another page of the conclusion to The Fur Trade in Canada : “the importance of manufactured goods to the fur trade made inevitable the continuation of control by Great Britain in the northern half of North America.”)

* * * *

In theoretical retrospect both the CPR and Intercolonial railways have been seen as parts of a John A. Macdonald nation-building strategy, elaborated in depth after the election of 1878. And the strategy included a new “National Policy” of aggressive tariff protection for a rising Canadian manufacturing sector, concentrated in Ontario and Quebec.

In practice, and here as elsewhere, the new political (and economic) enterprise Macdonald wanted to build was just the first self-governing dominion of the British Crown overseas — a continuing foothold for the greatest empire since Rome in North America. And necessity was the most important mother of most of “Old Tomorrow”’s policy inventions.

Macdonald began promoting tariff protection for Canadian manufacturers at innovative “political picnics” in the most populous province of Ontario during the summer of 1876. It was part of a strategy to revive his political career after his 62nd birthday in January 1877. And it arose in the wake of the Mackenzie government’s failure to revive the Reciprocity or free trade treaty of 1854–1866 with the United States.

In December 1873 Mackenzie had appointed George Brown of the Globe to the Senate. By early February 1874 Senator Brown was in Washington, testing the waters for a new Canada-US Reciprocity Treaty. Negotiations began in March. A draft treaty — which would have expanded the earlier free trade in primary resource products to include secondary manufactured goods — was soon available.

It was not popular among fledgling Canadian manufacturers, in Ontario, Quebec, and even Nova Scotia. And (as explained by P.B. Waite), the “draft Treaty went to the American Senate on June 18, 1874. It disappeared into the maw of the Foreign Relations Committee ; Congress adjourned [for summer] on June 22, and the Treaty was never seen again.”

As would become still clearer by the late 19th century, even with the Southern states restored to their places in Washington, many in the increasingly expansive new United States that arose from the ashes of the Civil War thought that if Canada wanted free trade with the more perfect union, it should follow all the other states enjoying this privilege and join the union itself. (In 1881 as well the population of the entire Dominion of Canada, at 4,324,810, was still notably smaller than the population of the then largest American state of New York, at 5,082,871.)

Meanwhile, a protective tariff to promote US manufacturing industry had been part of the “American System” urged by Henry Clay and others in the first half of the 19th century. And US tariffs averaged more than 30% from the end of the Civil War to the end of the 19th century. When the Macdonald government in Ottawa introduced protective tariffs on an array of goods between 17.5% to 20%, after it was elected in 1878, it was not reinventing any wheels. In some ways the later 19th century National Policy in Canada was just a belated far northern variation on the earlier American System in the United States.

* * * *

Federal subsidies for transportation improvements had been another plank in Henry Clay’s American System. On an exceptional far northern note, however, the Canadian Pacific Railway also came just in time for handling the Second Riel or Northwest Rebellion of 1885 much more expeditiously than the First Riel or Red River Rebellion, some 15 years before.

In the 21st century John A. Macdonald’s defeat of the 19th century Riel rebellions marks the defeat of potential directions cast aside by the old British Dominion of Canada, in which today’s independent Canadian member state of the United Nations has begun to take some fresh interest.

The North American miniature replica of medieval France that arose on the banks of the St. Lawrence River in the 17th and 18th centuries never advanced west of the Ottawa River. But the old French and Indian Métis culture of the first Canadian fur trade out of Montreal had made it all the way to the Rocky Mountains by the end of the French regime in 1763.

More than a century later Louis Riel was an authentic descendant of this early Canadian mixed-race (and bilingual) history. And in some minds the postage-stamp province of Manitoba created by the Red River Rebellion of 1869–70 was supposed to be a refuge for the French language, the Catholic religion, and the Métis community bred by the fur trade in the new Dominion of Canada’s great Northwest. In the 21st century the ghost of Louis Riel has also become a more mysterious inspiration for anglophone regionalism in Western Canada, and increasing numbers of mixed-race Canadians from all over the global village.

Back in the early 1880s it had become clear enough that Manitoba was not a refuge for the Canadian Métis. Many had moved further west to the Saskatchewan valley, along with smaller numbers of early anglophone settlers. To make a long story very short, Louis Riel, having returned to Canada from the United States, tried the Manitoba province-building strategy all over again, with the proclamation of something called the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan on March 19, 1885.

At first the strategy seemed to be working. On March 26 Riel’s military commander Gabriel Dumont and his Métis militia routed a force of more than 100 North West Mounted Police and Prince Albert settler volunteers near Duck Lake. On March 27 Fort Carlton on the North Saskatchewan River was evacuated, as Riel had earlier demanded.

This inspired support from sympathetic First Nations. And as Peter B. Waite much later explained “within four weeks the whole of the North Saskatchewan from Prince Albert west to the Alberta border and even beyond, was in Indian or Métis control.”

Yet in the late winter and early spring of 1885 Macdonald’s federal government in Ottawa had resources not available 15 years before. One was the North West Mounted Police. The other was the Canadian Pacific Railway. By early April the CPR had brought militia and two permanent artillery batteries from back east to Qu’Appelle, in what was then the District of Assiniboia in the Northwest Territories and is now the southern province of Saskatchewan.

Soon enough a large federal government force from Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and the Northwest Territories was in the region. And on May 9–12, Major-General Frederick Middleton’s troops decisively defeated a much less numerous force of Métis and First Nations led by Gabriel Dumont at Batoche, headquarters for Louis Riel’s Provisional Government of Saskatchewan.

Dumont fled to Montana. Riel gave himself up to Mounted Police scouts on May 15. The Plains Cree chief Poundmaker surrendered to Middleton on May 26. His fellow Cree chief Big Bear kept fighting until July 2, just after the 18th anniversary of the 1867 confederation.

As P.B. Waite has also explained : “No one really knows what was in Sir John Macdonald’s mind” on Louis Riel. But it is clear enough that the Macdonald federal government was determined to deal with him once and forever this time.

Riel had given himself up because he thought “politics” would save him. But George-Étienne Cartier was long dead. Langevin had visited the troubled North West in August 1884, but had not met a disappointed Riel. Francophone opinion in Quebec was still on Riel’s side, but it lacked a strong voice in Ottawa. Macdonald’s government charged Louis Riel with treason, under an ancient English statute also employed after the 1837–38 rebellions in the old two Canadas.

Riel’s lawyers argued he was insane (for which there was some compelling evidence in some respects, even though Riel denied the claim himself). A six-man Northwest Territories jury finally decided he was both sane and guilty of treason but recommended mercy. Macdonald’s government was determined to see him pay the traditional price for treason.

On November 16 Riel was finally hanged at 8:30 on a bright cold morning in Regina. The Macdonald Conservatives would remain in office for another decade (though Old Tomorrow himself would pass away in 1891). As Wilfrid Laurier and his colleagues seem to have realized at the start, however, the old party of Macdonald and Cartier began to lose its hold on French Canada when Louis Riel was hanged. It is only a mild exaggeration to say that the Liberals unofficially began their modern history as the natural governing party of Canada on November 16, 1885.

* * * *

John A. Macdonald’s centralizing, Ottawa-focused grip on the Canadian future began to atrophy in other ways after the hanging of Louis Riel.

To start with, whatever Macdonald and the exact text of what is now legally known as the Constitution Act, 1867 might suggest, those commanding the provincial government of Quebec had a deep and abiding interest in this other “sovereign” level of the Canadian federal experiment.

Then as now, Quebec had a francophone majority. Even in the (for the most part) limited adult male property-owning proto-democracy of the later 19th century, “la belle province” was the one great political arm that could be mobilized on behalf of the French Canadian nation, emerging alongside the larger transcontinental predominantly anglophone Canadian “political nation” (and in some telling ways older and wiser as well).

Moreover, in the later 19th century what finally linked the francophone majority in Quebec to the other anglophone-majority provinces was some amorphous new brand of British North American “Liberalism,” rising from the ashes of the Mackenzie regime in Ottawa.

Liberal premiers prevailed in Nova Scotia from 1882 to 1925, in New Brunswick (so-called “unofficially”) from1883 to 1906, and in PEI from 1891 to 1911. Quebec itself had Liberal premiers from 1887 to 1891 and then again from 1897 to 1936, Ontario from 1871 to 1905, and Manitoba from 1888 to 1890 and then again from 1915 to 1922. Only BC was somewhat different : its premiers claimed no party affiliation until 1903, and its first long Liberal regime took root between 1918 and 1928.

The first meeting of provincial premiers in the life of the confederation (a now annual mid-summer tradition in the 21st century) took place at the Interprovincial Conference of 1887. It was held in Quebec City at the invitation of Quebec’s Liberal premier Honoré Mercier, and chaired by Ontario’s Liberal premier Oliver Mowat. (Some anti-Liberal commentators of the day derided the “Mowat-Mercier Concordat.”) Other attendees included Nova Scotia’s Liberal premier William Fielding, New Brunswick’s (“unofficial”) Liberal premier Andrew Blair, and Manitoba’s second-last “non-partisan” premier John Norquay.

The 1880s also marked the start of a long line of “major judgments” by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom (JCPC), on the federal-provincial division of powers in what is now known as the Constitution Act 1867. And (as explained by the University of Alberta Centre for Constitutional Studies today) for half a century these decisions “disappointed the champions of a centralized federation and delighted those who wanted the provinces to be Ottawa’s equals.”

Key early cases included : Citizen’s Insurance Co. v. Parsons (1880), in which the JCPC restricted the federal government’s powers over trade and commerce ; Hodge v. the Queen (1883), where the JCPC ruled that “the Dominion Parliament has no authority to encroach upon any class of subjects which is exclusively assigned to provincial legislatures” ; and the Ontario Boundary Case (1884), in which the JCPC ruled against John A. Macdonald’s Ottawa and for the struggles of Oliver Mowat’s Ontario to keep pace with Quebec’s (and BC’s) territorial aggrandizement. (Or, it might be said, once British Columbia was admitted to the confederation with its present boundaries in 1871, Ontario and Quebec were bound to covet the lands beyond their smaller, more southerly limits of 1867!)

* * * *

One undisputed responsibility of the federal or dominion government under the Constitution Act, 1867 was “The Census and Statistics.” The Act also provided that a “general Census of the Population of Canada …be taken in the Year One thousand eight hundred and seventy-one, and in every Tenth Year thereafter.”

Something of the now freshly relevant potential directions cast aside by the old British Dominion of Canada when the Macdonald government hanged Louis Riel in 1885 can still be dimly apprehended in the dominion’s second census of 1881. At this point censuses were conducted by the federal Department of Agriculture. And the mastermind of the 1871 and 1881 exercises was Joseph Charles Taché, first deputy minister of agriculture (ie the senior civil servant in the department).

Joseph Charles Taché was in fact a nephew of Étienne-Paschal Taché — a Canada East partner of John A. Macdonald’s in more than one double-barrelled government of the old United Province of Canada. Lest anyone think Joseph Charles’s appointment was just a sad example of nepotism in the public service of the early Canadian confederation, he also had other “impressive credentials, which included a medical qualification as well as legislative, journalistic, and academic experience.” He served as first deputy minister of agriculture in the new dominion from 1867 to 1888.

A little of the flavour of the 1881 census can be gleaned from the classification of “Origins of the People” — which divided the 4,324,810 reported Canadian residents of the day, coast to coast to coast, into 19 different alphabetically ordered groups : African (0.5%), Chinese (0.1%), Dutch (0.7%), English (20.4%), French (30.1%), German (5.9%), Icelander (0.02%), Indian (or First Nations — 2.5%), Irish (22.1%), Italian (0.04%), Jewish (0.02%), Russian and Polish (0.03%), Scandinavian (0.1%), Scotch (16.2%), Spanish and Portuguese (0.03%), Swiss (0.1%), Welsh (0.2%), Various Other Origins (0.06%), and Not given (0.9%).

(It is all too true as well that 99% of Canada’s Chinese-origin residents in 1881, eg, were in British Columbia. Most worked on the challenging construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway through the dangerous Fraser Canyon in the Coast Mountains, closest to the Pacific Ocean. And as one sign of narrower times ahead, in 1885 the federal government began levying a head tax on new Chinese immigrants. Chinese immigration would be banned altogether in 1923 — and the ban was not repealed until 1947.)

Joseph Charles Taché retired as deputy minister of agriculture in 1888. His role in organizing the decennial census was taken over by a new officially designated “Dominion statistician,” George Johnson. And as explained in the Statistical Year-Book of Canada for 1892 : “No particulars of ‘origins’ were taken in 1891, and very wisely so, as they were of no specially instructive value and only tended to perpetuate race distinctions.” (This may also have had something to do with what Liberal eminence Edward Blake, in an 1890 parliamentary debate on the 1891 Census, called “a growing desire on the part of Canadians to be returned as belonging to the Canadian nationality” — something that would not finally become officially possible for another 100 years.)

The Census did return to reporting particulars of “origins” in 1901, but the classification scheme was somewhat different than it had been in 1881. And the Canada-wide numbers for 1901 were reported in a particular hierarchical order of government-favoured cultures, as it were. First came British origins in four sub-groups : English (23.47%), Irish (18.41%), Scotch (14.90%), and Others (Welsh, Manx, and so forth — 0.25%). This was followed by what might be called a broad group of other Europeans, led of course by descendants of Canada’s first European mother country : French (30.71%), German (5.78%), Dutch (0.63%), Scandinavian (0.58%), Russian (0.53%), Austro-Hungarian (0.34%), Italian (0.20%), Jewish (0.30%), Swiss (0.07%), and Belgian (0.06%). Finally there was a non-European group, led by what the Constitution Act, 1982 would much later call the “aboriginal peoples of Canada” : Half-breeds (only rendered as Métis in the French copy — 0.64%), Indian (or as we might now say First Nations — 1.74%), Chinese and Japanese (0.41%), Negro (0.32%), Various origins (0.07%), and Unspecified (0.59%).

What the census and related statistical documents finally suggest is that the early Dominion of Canada of the 1870s and 1880s was still on some edge of the quite aggressive British imperial directions that marked its earlier 20th century incarnation. And, hinting at the more indigenously Canadian legacy of the Riel (and other) rebellions for the longer-term future, George Johnson’s Statistical Year-Book of Canada for 1892 also urged that : “The origin of the word Canada is obscure, but the derivation now generally accepted is that from an Indian word, ‘Kannatha,’ meaning a village or collection of huts, and it is supposed that Jacques Cartier, hearing this word used by the Indians with reference to their settlements, mistook its meaning, and applied it to the whole country.”

* * * *

David Worton, in his 1998 history of what finally became the Dominion Bureau of Statistics in 1918, alludes to “the extended dispute concerning US statistics on the alleged exodus of population during the early 1880s from Canada to the United States.” And this also raises the somewhat harsh subtitle of P.B. Waite’s still unequaled Canadian history classic of 1971, Canada 1874—1896 : Arduous Destiny.

Throughout the 19th century the United Kingdom remained the leading source of migrants to all parts of British North America by far. And it does seem true enough that some who migrated from the United Kingdom to Canada in the late 19th century soon found opportunities in a very aggressively expanding United States next door more alluring.

For at least large as well as small numbers of old and new Americans after the Civil War (and especially after “the Long Depression, 1873–1878”), the American economy and wider society was in the midst of dramatic growth.

At the time the era’s great critic and literary exemplar Mark Twain called it the Gilded Age. Matthew Josephson in the 1930s would write about The Robber Barons : The Great American Capitalists, 1861–1901. In the early 21st century Kevin Phillips provocatively chronicled “The Rise of the Great American Fortunes, 1865–1900.”

Most compellingly of all, perhaps, from the standpoint of the great mass of the people, the early 20th century American literary historian Vernon Parrington re-conceived Mark Twain’s Gilded Age as “The Great Barbecue” — which worked for some but not for others.

There seems little doubt that quite this kind of feast was not happening during the first generation of the 1867 confederation in Canada, in any part of the country. As in its deeper past Canada was (rather haphazardly) pursuing a more arduous destiny, with less strictly materialist objectives. International migrants who coveted the raw economic benefits of the Great Barbecue most (and were in a position to at least gain a few of them) probably were best advised to move to the United States.

At the same time again, Canada did not at all lose population during the later 19th century. The new dominion of the north grew by 17.2% between 1871 and 1881, by 11.9% between 1881 and 1891, and by 11.1% between 1891 and 1901.

This was in fact no match for the hyper-dynamic United States in the age of The Great Barbecue. It grew by 30.2% between 1870 and 1880, 25.5% between 1880 and 1890, and 21.0% between 1890 and 1900. Yet even in America nothing lasts forever. A mild reversal of fortune was in the wings. In the first two decades of the 20th century, the first self-governing dominion of the global British empire (on which the sun never dared to set) would actually grow faster than the rising (and mostly friendly) US giant next door.

* * * *

Before rushing too quickly into Wilfrid Laurier’s new age of sunny ways, in the 20th century that belonged to Canada (well … the first decade or so anyway), there are some last details to be noted in the life of the post-1878 John A. Macdonald Liberal-Conservative party, long after the too-early death of George-Étienne Cartier.

If it is more than a little foolish to pretend that Macdonald is any kind of Canadian George Washington, on several fronts, there can be no doubt that he played a big and in some ways constructive role in launching the Canadian confederation of 1867. And after further crucial additions, this piece of 19th century political architecture remains in business for the people of Canada today — albeit with many much-needed improvements always still looming in the free and democratic air.

John A. Macdonald’s retail political talents in his time and place are beyond question. The Pacific Scandal doomed him in 1874. But he went on to win four successive majority governments in 1878, 1882, 1887, and 1891. On Murray Beck’s calculations of the late 1960s, he won at least a bare 50% of the popular vote each time as well. And all four elections were held by secret ballot and more or less on the same day (September 17, 1878, June 20, 1882, February 22, 1887, and March 5, 1891).

Macdonald’s main contribution to the long democratic expansion in the electoral franchise begun by the Mackenzie Liberals, however, was to slow the process down. At confederation qualifications for voters in federal elections were those determined by provincial governments for provincial elections. In 1885 — year of the Northwest Rebellion and the CPR — Macdonald’s Electoral Franchise Act established more or less uniform federal qualifications “higher than they had been before in most provinces.” Broadly, they confined voting in federal elections to male British subjects (“by birth or naturalization”) 21 years and older, who owned real estate worth $300 in cities, $200 in towns, or $150 in rural areas, or who paid at least $2 per month or $20 a year in rent, or who had an annual income of $300 or more. (At a time, of course, when $1 had vastly more purchasing power than it has in the early 21st century.)

The Act continued to effectively prohibit most First Nations Canadians from voting. And, as explained by Elections Canada today : “Persons of ‘Mongolian and Chinese race’ were expressly deprived of the right to vote. According to John A. Macdonald, persons of Chinese origin ought not to have a vote because they had ‘no British instincts or British feelings or aspirations’.” This was the same Macdonald who declared “A British subject I was born — a British subject I will die,” during his last election campaign in the winter of 1891. His party won another majority government on March 5. But The Old Chieftain (to cite the subtitle of the 1955 second volume of Donald Creighton’s almost hagiographic biography) was now 76 years old, and not in good health. He fell seriously ill during the spring, and passed away in Ottawa on June 6.

It is a testament of some sort that even without the man himself Macdonald’s government carried on for another five years. But it never found a serious successor. The role of prime minister passed from John J.C. Abbott (June 16, 1891–November 24, 1892) to John S.D. Thompson (December 5, 1892–December 12, 1894), to Mackenzie Bowell (December 21, 1894–April 27, 1896) to Charles Tupper (May 1, 1896–July 8, 1896). Then Tupper and his old Canadian Tory government were defeated by Wilfrid Laurier’s at long last effectively reconfigured Liberal Party of Canada in an election held on June 23, 1896. And the new age of sunny ways officially began in the still quite youthful confederation of 1867.

FROM

Children of the Global Village

Democracy in Canada Since 1497

Randall White

eastendbooks 2024

(For background on the larger series of which this is a part, see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic.)

PART III

DOMINION OF CANADA, 1867—1963

2

The sadness of Hector-Louis Langevin … Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal Government 1873—1878 … The Canadian Pacific Railway … Macdonald’s “National Policy” of tariff protection … Northwest Rebellion and death of Louis Riel 1885 … The Revolt of the Provinces and the JCPC …Censuses of Canada, 1871—1901… Population growth in Canada and the Great Barbecue in the USA .. The end of the age of John A. Macdonald and his Liberal-Conservative party