First self-governing dominion of the British empire : Further founding moments, 1867—1873

Sep 15th, 2016 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage NowIn the early 21st century it is not easy to think constructively about the now largely vanished first self-governing British dominion of Canada.

The northern North American universe from the late 1860s to the early 1960s is both too remote yet still too close at hand.

Then there is the late historian Ramsay Cook’s quip that the 19th century did not end in Canada until 1950. And the historian Frank Underhill’s allusion of the 1920s to the received wisdom of his youth : “Our Canadian history is dull as ditchwater and our politics is full of it.”

Yet if we can even just half-liberate our own primeval memories of the mid 19th to mid 20th centuries (from many different parts of the global village), there are still intriguing Canadian variations on the larger themes of democratic development better known elsewhere.

Blowing in the Wind

Democracy was a practical if not quite yet a philosophical priority of the Canadian federalist experiment launched on July 1, 1867. Its first serious order of business was a leisurely first election, beginning on August 6 and carrying on until September 20.

The new Canada was also still just the first self-governing dominion of the British empire, ultimately accountable (in theory) to Queen Victoria. And John A. Macdonald had been appointed first prime minister before the election took place. A 2009 Canadian House of Commons procedural manual explains : “On May 24, 1867 … John A. Macdonald was formally commissioned by Lord Monck to form the first government under Confederation. On July 1, 1867, the First Ministry assumed office with Macdonald serving as Prime Minister.”

“Lord Monck” here was Charles Stanley Monck, appointed Governor General of British North America by UK Prime Minister Lord Palmerston (as advised by his colonial secretary, the Duke of Newcastle) late in 1861. Monck was the immediate presence of the imperial government throughout the confederation process. And he was sworn in as the new Governor General of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867.

By this point Monck was in fact eager to return to managing his own landed estates (in Ireland). But he agreed to remain as Governor General of the new Dominion of Canada while it found its first feet. Not long before he finally left, late in 1868, Macdonald wrote to a friend : “I like him amazingly and shall be very sorry when he leaves, as he has been a very prudent and efficient administrator of public affairs.”

* * * *

The 1867 election itself says a lot about the limitations of early Canadian democracy — and the fragility of the new Dominion of Canada.

The Tokugawa Shogunate (1603–1867) had not quite ended in Japan. Modern transportation and communications were still in their infancy. It is not entirely surprising that the first general election in the new Canada should take up the entire last six weeks of the summer of 1867.

The arrangement was in any case open to even more manipulation by the executive branch of government than usual, in the last days of manly oral voting in public polling places. And the voters were confined to adult males with as much property as well over half their number did apparently have (in the golden age of the English North American family farm — and the French habitant idyll of the lower St. Lawrence valley.)

Meanwhile, John A. Macdonald did not dominate his peers through any practical authority granted by Lord Monck (to say nothing of Queen Victoria across the seas). It literally drove him to drink. But he finally at least started to blend the various rival regional and other voices into a new tradition of compromise, first apprehended in the old United Province.

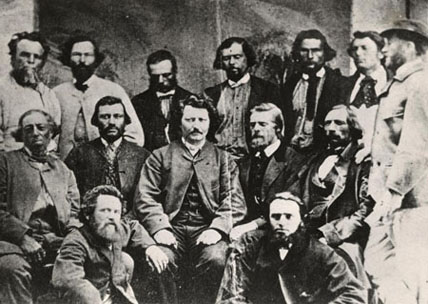

In this spirit, the 12-man cabinet Macdonald chose to take office on July 1, 1867 is customarily called a coalition government : a non-partisan founding “First Ministry.” It included the Quebec Bleu George-Étienne Cartier (officially Minister of Militia and Defence — a helpful symbol for French Canada?), the New Brunswick Liberal Samuel Leonard Tilley, the Ontario Tory Alexander Campbell (serving as Postmaster General from the Senate!), and the old Ontario Clear Grit Reformer William McDougall.

With such preparations Macdonald’s first coalition ministry did well among the voters of Ontario and Quebec, and was not unappreciated in New Brunswick. What is surprising (especially in the 21st century?) is that it did so badly in Nova Scotia.

The 1867 election summary on the Parliament of Canada website today addresses the issue directly. Almost all MPs who won Nova Scotia seats in the new federal parliament followed the province’s “Anti-Confederate” faction, led by the Liberal reformer Joseph Howe. The “only Confederation supporter elected was Charles Tupper.”

A year and a half later, the ultimate bottom line was that the imperial government in London would not hear of repealing confederation, as the Anti-Confederates wanted. Halifax was still a Royal Navy base. Nova Scotia was loyal to the widowed Queen who would soon be proclaimed Empress of India, if not yet to the new British dominion dominated by the old Canada. Joseph Howe finally settled on “a campaign for so-called ‘better terms’,” waged from within Macdonald’s cabinet.

Howe was President of the Privy Council, January 30–November 15, 1869. Then he officially became Secretary of State for the Provinces, November 16, 1869–May 6, 1873. (And on December 8, 1869 the job of Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs was added to the responsibilities of Secretary of State for the Provinces.)

* * * *

Another regional revolt had begun on May 15, 1867, when the new Canadian Bank of Commerce (later CIBC) opened for business in Toronto.

The bank’s corporate history in the 21st century makes no secret of its origins : “The Honourable William McMaster, a prominent Toronto businessman … was the principal founder of the bank and its first president.” He was concerned about “Montreal’s influence over the economy” west of the Ottawa River. And he started the Bank of Commerce “mainly as competition for the Bank of Montreal.”

For its part the Bank of Montreal — “Canada’s first bank” (and later BMO) — had been founded in 1817 on profits from the fur trade. It was in some ways a descendant of the North West Company that Harold Innis would later call “the forerunner of confederation.”

At the same time, a Bank of Upper Canada had been established in 1821. It was ultimately headquartered in the old Town of York that became the City of Toronto in 1834. It had become official banker to the United Province of Canada in 1850. But the Bank of Montreal took over (or arguably recovered) this position in 1864. And the Bank of Upper Canada went out of business in November 1866.

All this reflected confederation-era muscle-flexing by the larger Montreal financial community. A generation later the Merchants Bank of Halifax (founded in 1864) would become the Royal Bank of Canada (later RBC), headquartered in Montreal. Toronto as a financial centre would be a junior partner to Montreal until the middle of the 20th century.

Meanwhile, the United Province’s pioneering adoption of a Canadian dollar in the 1850s had laid foundations for the elaboration of an independent financial system during the early days of the wider Dominion of Canada, in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

This project began with the draft of a federal Bank Act introduced in 1868 by John A. Macdonald’s first minister of finance, the Montrealer John Rose, after extensive consultation with the Bank of Montreal.

Beyond Montreal, Rose’s draft legislation met increasing opposition. Late in 1869 he was replaced by Francis Hincks from Ontario — former United Province co-premier (Hincks-Morin, 1851–1854), and cashier of an ill-fated Bank of the People in the old Upper Canada (1835–1840).

For better or worse, Hincks’s Bank Act of 1871 established a Canada-wide branch banking system, unlike the more common independent regional banks of the United States. The 1871 Bank Act in Canada was also set to expire in 1881. And this bequeathed a more unambiguously far-sighted mandatory revision of Canadian financial services legislation every 10 years (eventually changed to every five years in 1992).

The Northwest Territories and Louis Riel’s Manitoba

On the long view, the first few years of the new confederation were most urgently preoccupied with securing the full transcontinental geography pioneered by the fur-trading North West and Hudson’s Bay companies, for some emerging Canadian people. (Those who had already voted, eg, in the six-week election of 1867.)

The initial Ottawa manager of this file was not John A. Macdonald, but his old French Canadian partner, George-Étienne Cartier. Monck had thought Macdonald himself should go to London to negotiate the transfer of the Hudson’s Bay Company lands to the new dominion, in the early autumn of 1868. But Macdonald, still most worried about Joseph Howe’s Nova Scotia, convinced Monck to settle on Cartier and William McDougall — with Cartier as the “trusted man, the man in charge” (W.L. Morton).

Macdonald may have more clearly understood as well that French Canada’s assent to just how the North West would be brought into the new British dominion could not be altogether taken for granted. Or as Cartier himself put it, some said “that he and his friends in Lower Canada were opposed to the acquisition of the North West.” But he “was never opposed to the acquisition of the Territory per se, but only to its being acquired by Ontario, adding to the undue influence of Ontario.”

So Cartier from Quebec and McDougall from Ontario traveled across the Atlantic to the capital of the global empire in London, to arrange the fine print on the old Hudson’s Bay Company lands. They returned with a deal that some said was good for Canada — and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The fledgling Canadian federal government paid the Company £300,000 in cash. The Company would also receive 20% of newly subdivided former Company land, and various lands surrounding established trading posts.

* * * *

The resulting new Northwest Territory of Canada (or North-West Territories — foreshadowed in David Thompson’s awesome fur-trade map of the earlier 19th century) was geographically vast. It included the present-day northern parts of Quebec and Ontario, the three future Prairie Provinces, and much of the present-day three northern territories.

Practical political problems soon arose with a June 1869 federal bill for the provisional government of this sprawling new northern and western region. And these problems were more narrowly focused on the Red River settlement that had grown haphazardly over the past half century, around the present-day City of Winnipeg. (Where the Red and Assiniboine rivers meet — also home to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s trading post Fort Garry after 1821, and before that the North West Company’s Fort Gibraltar.)

At Red River Cartier’s abstract concern that the North West must not add “to the undue influence of Ontario” found a real-world analogue in the mixed-race Métis community (Indian/Indigenous-European and especially “French and Indian”), handed down by Harold Innis’s Fur Trade in Canada.

There were already early anglophone settlers around Fort Garry — from Ontario and elsewhere (going back to Lord Selkirk’s struggles in the early 19th century). But at this point the Red River Métis community (francophone and anglophone) still had more than three-quarters of some 12,000 people in the region. More than half shared a language and a religion with George-Étienne Cartier. All were concerned that Ottawa’s surveyors might disturb traditional lands . And they worried about the very open-ended (and quite undemocratic) June 1869 bill for the new Dominion of Canada’s provisional government of the former Hudson’s Bay Company lands — in which the lieutenant governor “will be for the time Paternal despot.”

Their worries increased exponentially late in September 1869, when John A. Macdonald appointed William McDougall first lieutenant governor of the new Northwest (or North-West)Territories of Canada. The French Catholic Cartier from Quebec had led the negotiations in London. But now it at least looked like Macdonald believed the Anglo Protestant McDougall from Ontario was better suited to the new territory’s most likely destiny, as a home to certain continuing “British” variations on the English-speaking agrarian democracy of the North American family farm.

* * * *

Inspired by the military discipline of their annual prairie buffalo hunt, the Red River Métis established a “National Committee.” It included Louis Riel, the 25-year old son of a noted local family, educated by the Sulpician fathers at the Collège de Montréal (like Cartier, LaFontaine, and Papineau). At the end of October 1869 the Métis National Committee prevented the newly arrived Lieutenant Governor William McDougall’s “entry into Red River.” On November 2 it seized Fort Garry from the Hudson’s Bay Company.

From here until almost the last imperial force of British regulars in North America arrived at Red River late in August 1870, the first Riel or Red River “rebellion” (or “resistance”) had constructive sides, that effectively created the first Canadian prairie province of Manitoba.

In the Canadian Encyclopedia today Louis Riel is characterized as “Métis leader, founder of Manitoba.” A Louis Riel opera was written for the centennial of the 1867 confederation. Statues of Louis Riel appeared on the grounds of the Manitoba legislature in 1971 and 1996. The historian J.M. Bumstead published Louis Riel v. Canada: The Making of a Rebel in 2001. The cartoonist Chester Brown’s Louis Riel : a comic-strip biography was “published as a book in 2003 after serialization in 1999–2003.”

While the old Dominion of Canada was still alive and well, from the late 1860s to the early 1960s, Riel and his rebellions (in 1869–70 and then again further west in 1885) were more controversial.

On one bottom line, in 1870 the Red River was a long way for any substantial British regular or Canadian militia force back east to reach quickly. And Riel and his National Committee followers (Métis and other, francophone and anglophone) did want to be part of the new Canada (Montreal was their historic fur-trade metropolis) — but on their own terms.

The Protestant reformer from Ontario’s British Canadian variation on the Anglo-American frontier, Lieutenant Governor McDougall, had no effective armed force of his own. And he was too foolishly confrontational with the warriors of the Métis National Committee in buffalo-hunt formation. Macdonald’s old partner George-Étienne Cartier already had serious sympathy for Louis Riel, a francophone Catholic educated in Montreal (at the same alma mater as Cartier!). A brooding, disheartened William McDougall, feeling betrayed by his colleagues in Ottawa, was back in Ontario by the end of 1869.

Macdonald (and Cartier) sent more helpful interlocutors — including Abbé Jean-Baptiste Thibault and Donald Smith of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Riel finally established a provisional government with broad support in the Red River region, and an equal-French-and-English structure. In the early spring of 1870 this government sent delegates to Ottawa. They were first arrested as rebels, and then sent to talk with Macdonald and Cartier. (Joseph Howe, Secretary of State for the Provinces, also played a role. He had traveled to Red River himself in the fall of 1869.)

It is only a little too much to say that Riel’s provisional government effectively negotiated the initially quite small “postage-stamp” Province of Manitoba with the new Canadian federal government, as an aspiring vehicle of Red River Métis aspirations. At the same time, back on the ground at Fort Garry Louis Riel made what would prove an insurmountable political blunder. On March 4, 1870 he went ahead with the execution by firing squad of the rambunctious and fiery Protestant “Orangeman” Thomas Scott (also known as “an unpopular hooligan”), on a charge of “treason against the provisional government.”

Staunch Partisans of the Tories (and Others)

Ontario has always been more culturally diverse than some regional folklore suggests. But in 1870 it did enjoy substantial numbers of Anglo Protestant Orangemen from Northern Ireland and elsewhere. And many among them had become staunch and sometimes even aggressive partisans of the colonial Tories in Canada.

It could also be said that Tory Orangemen opposed the French and Indians on the first Canadian northwestern frontier through conservative cultural chauvinism. McDougall and the Ontario Clear Grits only somewhat differently saw them as obstacles to liberal progress.

In Ontario and elsewhere Orangemen were an important part of John A. Macdonald’s electoral base as well. Led on by various English-language newspapers, they were incensed at Louis Riel’s execution of Thomas Scott — “the foulest crime that stains the page of Canadian history.”

Finally, the government in Ottawa did not feel it could extend the same amnesty to Riel that it ultimately offered others in the rebellion. Many in Red River believed George-Étienne Cartier continued to support amnesty for all. But even Cartier’s key objective was the apparent broader provisions of the Manitoba Act, 1870, to preserve the French and Indian culture of the Canadian fur trade (and/or the majority French Catholic culture of the new Province of Quebec) in the still newer Province of Manitoba.

* * * *

Orangemen and others back east were also urging that a military expedition be sent to Red River, to put a decisive end to Riel’s “rebellion” and give the new Canadian Province of Manitoba a proper constitutional beginning.

Macdonald (and Cartier, as Minister of Militia and Defence) could see other good reasons for an expedition. It would show adjacent American annexationists that the “greatest empire since Rome” was not about to let the excitement at Red River serve as an excuse to make the vast new Northwest Territories of Canada part of the United States.

Plans were finally laid for an expeditionary force to depart from Toronto in May 1870. It was led by Colonel Garnet Wolseley (a soldier of the global empire who would later rescue at least the mission of “Chinese Gordon” at Khartoum in Egypt, with some help from Canadian voyageurs!).

As a matter of great consequence for Wolseley’s Red River Expedition, beyond the Great Lakes the Canadian route out west followed by William McDougall, Joseph Howe, and everyone else at this point typically went through the already more developed United States.

The all-Canadian or British North American northern wilderness route beyond Lake Superior was reserved for the remaining paddling-and-portaging voyageurs of the transcontinental fur trade — and related adventurers who still cultivated the arts and crafts of the Great Lakes Indigenous peoples.

Yet a few politicians were one thing. In 1870 President Ulysses S. Grant’s post-Civil-War United States government did not want a British and Canadian force of more than 1,000 armed soldiers traveling through its territory. West of Lake Superior the Wolseley Expedition had to emulate (and be assisted by) the fur-trade voyageurs.

As summarized in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography today, Garnet Wolseley “moved a force consisting of nearly 400 British troops, over 700 Canadian militia, and a large party of civilian voyageurs and workmen from their port of embarkation [on Georgian Bay north of Toronto] … to the Red River between 3 May and 24 August [1870], without losing a man. Altogether the expedition made 47 portages and ran 51 miles of rapids.”

(There is an 1877 painting by Frances Hopkins, canoeing artist-wife of the Hudson’s Bay Company official, Edward Hopkins, called “The Red River Expedition at Kakabeka Falls, Ontario.” It captures something of the almost four-month northern wilderness journey in the spring and summer of 1870 — just as Georgia became the last state of the short-lived southern confederacy to rejoin the Union next door.)

* * * *

According to legend Garnet Wolseley’s Red River Expedition arrived at Fort Garry in the rain, on August 24, 1870.

This had been the headquarters of Louis Riel’s provisional government. Yet it had now become clear that there would be no immediate amnesty for the Red River Catholic rebel who had put the Protestant Orangeman Thomas Scott in front of a firing squad.

Louis Riel also feared that Orangemen in the Ontario and Quebec militia regiments accompanying Wolseley’s British regulars had plans to assassinate him. Just before Wolseley arrived at Fort Garry Riel and his close followers had fled, ultimately to exile in the United States. (Like the old Canadian rebel leaders Mackenzie and Papineau, a generation before.)

In fact, aggressive military action against the Red River “rebellion” was not the declared policy of Macdonald and Cartier’s new federal government. Wolseley’s expedition had other purposes. One was was to show Grant’s United States government that the empire supported the rapid expansion of the new Dominion of Canada into the old fur-trading North West. Another was to ensure that the first lieutenant governor of the new Province of Manitoba, the Nova Scotia Father of Confederation Adams George Archibald, could take up office without incident.

Appointed by Macdonald (and/or Cartier?), Lieutenant Governor Archibald had been sworn in by the new Governor General of Canada, John Young, 1st Baron Lisgar, at Niagara Falls in August 1870. Archibald arrived safely at Fort Garry on September 2 and settled in to his new job.

Colonel Wolseley saw this as evidence that his main mission was complete. He and his British regulars set out on a very long journey back east to the United Kingdom, leaving the Ontario and Quebec militia to keep order. (And also, unhappily, to intimidate – and in a few cases actually harm — any Red River Métis still too attached to memories of Louis Riel, even if this was not declared dominion government policy.)

Pacific Northwest … Salish, Tlingit, and Tsimshian

Lieutenant Governor Archibald officially proclaimed the new Province of Manitoba on September 6, 1870. At this point it may have seemed that while amnesty for Louis Riel was not immediately possible, many of his objectives had been achieved. According to the federal Manitoba Act, in the new province “English- and French-language rights were safeguarded, as were Protestant and Roman Catholic educational rights.”

Yet just to start with, in this earliest incarnation Manitoba really was a “postage-stamp province” — a modest rectangle of land around present-day Winnipeg. The vast majority of the new Northwest remained intact, and in the hands of the federal government. (Though the federally appointed lieutenant governor of Manitoba would also serve as lieutenant governor of the surrounding Northwest Territories until 1876.)

Moreover, unlike the four original provinces of the 1867 confederation (or the two on either coast added in 1871 and 1873), control over Manitoba’s natural resources remained with the federal government in Ottawa until 1930 — a practice eventually extended to all three prairie provinces finally created from the new Northwest Territories, “to provide funds for colonization and railway building.”

Yet even the old Hudson’s Bay Company lands in their entirety could not bring the full reach of the northern North American transcontinental fur trade into the new Dominion of Canada. For that the Crown Colony of British Columbia between the Rocky Mountains and the Pacific Ocean would also be required.

Here again George-Étienne Cartier not John A. Macdonald would lead. In this case the problem was Macdonald’s health, under all the stress and strain of getting the new confederation started (and no doubt his own over-consumption of alcoholic beverages to help the project along).

On the early afternoon of May 6, 1870 Wolseley’s expedition had left Toronto a few days before. The new Manitoba Act was wending its way through parliament in Ottawa. And John A. Macdonald was suddenly seized by acute pain while waiting for lunch in his corner office, in the East Block of the still quite new parliament buildings. As his most ardent biographer Donald Creighton would much later explain : “He felt his senses whirling, spinning, dropping into a dark void of agony. He clutched the table, swayed, tried to recover his balance, and fell blindly across the carpet.”

* * * *

Some feared John A. Macdonald had reached the end of his life. But he spent the next few months and then the entire summer of 1870 recuperating, ultimately in a comfortable house on the red sands of Prince Edward Island. In this strategic but relaxing location he made close to a complete recovery.

Meanwhile, there were arrangements for a delegation from British Columbia to visit Ottawa, to discuss joining the new confederation. It arrived early in June, and meetings began on the 6th. Cartier “acted as prime minister, and the change gave to Canadian policy the dash and audacity … of the genial and headstrong Frenchman” (W.L. Morton, 1964).

As already noted, British Columbia at the start of the 1870s had just been created in 1866 — as an amalgamation of the earlier Vancouver Island and British Columbia mainland colonies. It still had a First Nations majority (including prosperous communities with arresting totem poles along the Pacific coast — Ditidaht, Haida, Haisla, Kwakwaka’wakw, Nisga’a, Nuu-chah-nulth, Nuxalk, Salish, Tlingit, and Tsimshian).

These Indigenous peoples were not directly recognized in the government of the crown colony. Neither were most other people in the non-aboriginal minority. British Columbia before it entered confederation did not yet have the early democracy of responsible government.

By 1870 the non-responsible governor, Anthony Musgrave, was happily enthusiastic about BC’s joining the northern North American confederation. (Perhaps because the imperial government in the United Kingdom which appointed him felt that way too?)

The three-man delegation Governor Musgrave sent to Ottawa in the spring of 1870 (via the US Central and Union Pacific railways) did not include the two British Columbians most enthusiastic about the new Canada — John Robson (as in Robson Street in Vancouver today) and the unusually named unusual individual, Amor de Cosmos. But it had a clear set of conditions, almost all of which at least Cartier and his accompanying cabinet colleagues Hincks and Tilley were happy to fulfill.

The dominion government would assume the former colony of British Columbia’s debt, and provide the new province with a subsidy based on “a generous estimate of population.” Exact arrangements for responsible government were left to the old colonial administration — which finally settled for “a constitution modeled on that of Ontario”!

Most crucially for the near-term future, the dominion government agreed that an all-Canadian transcontinental railway, linking the eastern provinces with the Pacific coast (and the Intercolonial Railway to the Atlantic coast), would be “started within two years and completed within ten years” of the agreement bringing British Columbia into the dominion.

More than a few opposition members of the new Canadian House of Commons were skeptical about the immediate common sense of what finally became the Canadian Pacific Railway. (It would nonetheless be completed only four years late in 1885.)

Cartier, however, had been a solicitor for the Grand Trunk Railway, headquartered in Montreal (with a financial higher management in London, England). He was full of enthusiasm for a similar link to the Pacific Ocean, that would enhance Montreal’s metropolitan role in the new Dominion of Canada, on the model of the old North West Company’s transcontinental fur trade — “built on the work of the French voyageur, the contributions of the Indian, especially the canoe, Indian corn, and pemmican, and the organizing ability of Anglo-American merchants” (Innis).

Cartier made clear that his friends in parliament from Quebec would vote for the Pacific Railway, regardless of faint-hearted objections elsewhere. And he used his genial charm to mobilize required further legislative support from Ontario and the two Maritime provinces.

British Columbia officially joined the first self-governing dominion of the British empire on July 20, 1871. A few months before the engineer J.W. Trutch, one of the delegates to Ottawa in June 1870, had declared : “We must all remember in BC that to Sir George Cartier and his followers in Lower Canada we owe the position we are now in and especially the Canadian Pacific Railway.”

* * * *

John A. Macdonald had fully recovered from his 1870 breakdown by the second general election of the new Dominion of Canada in 1872. In some ways this election had a lot in common with the first election of 1867. It unfolded over an even longer time period, from July 20 to October 12. And (except in New Brunswick, where the secret ballot had been adopted in 1855) it was still based on manly oral voting in public polling places.

Similarly, the subsequent two dominant parties in federal politics Conservatives and Liberals, on the model of the United Kingdom — had still not quite congealed in the new Canada.

Macdonald’s (and Cartier’s) party was still known as “Liberal Conservative.” The later Liberals were still divided among assorted Liberals and Reformers in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, les Rouges and a short-lived Parti national in Quebec, the old Clear Grit and other Reformers in Ontario, and still rather vague forces in Manitoba and British Columbia. They also lacked a formally chosen leader (although Edward Blake from Ontario had some recognition).

At the same time, Macdonald’s non-partisan “First Ministry” that met the electorate in 1867 had begun to unravel into something more like an serious Conservative or at least “Liberal Conservative” party. In 1872 it fared better in Nova Scotia, finally not quite so well in New Brunswick, ahead by more than 10 seats in Quebec, down by about the same number in Ontario, and ahead by quite large numbers in the new provinces of Manitoba and BC. On balance Macdonald’s government at first commanded a modest but working majority across the new dominion.

At the same time again, two crucial cabinet ministers initially lost their seats in 1872 — Cartier in his Montreal East riding, and finance minister Francis Hincks in his Ontario riding of Brant South.

At the same time yet again, over the long election period the results back east were generally known even weeks before anyone voted in the two new western provinces. (And this began a practice that would have milder analogues down the road, even with elections taking place on a single day.) Louis Riel, not yet quite reconciled to his US exile, was actually running for a seat in Manitoba, but then stood down in favour of Cartier, on news of the defeat in Montreal East. As the sun set much furthest west, Hincks found a seat in Vancouver to compensate for his loss in Brant South.

Pacific Scandal, Red Coats, Red Sand

As a sign of the more partisan pressures faced by Macdonald’s government in 1872, he and a few colleagues were also more aggressive than they ought to have been about requesting financial assistance to help win the second general election, from railway interests competing for government contracts to build the Canadian Pacific line promised to British Columbia.

The campaigns of George-Étienne Cartier and Hector-Louis Langevin in Quebec were prominently involved. Most notoriously, a subsequently revealed telegram from Macdonald himself to a legal adviser of the railway developer Hugh Allan read : “I must have another ten thousand; will be the last time of calling; do not fail me; answer today.”

Assistance of this sort may have helped Macdonald’s government win at least a working majority in parliament, in the two-and-a-half-month election of 1872. But by the spring of 1873 it had burst upon the general public as “the Pacific Scandal” — the “first major political scandal in Canada after Confederation,” which “involved the taking of election funds by Prime Minister John A. Macdonald in exchange for the contract to build the Canadian Pacific Railway.”

(And this marked the start of a long and dishonourable but enduring Canadian political tradition of defeating federal governments by mobilizing scandals against them — as revived in the “Adscam” squabble that helped the Harper Conservatives win their first minority government in 2006.)

In the spring, summer, and early fall of 1873 growing public understandings of the depths of the Pacific Scandal — and popular demands for some kind of sanction — helped galvanize a Liberal opposition from all parts of the new confederation.

It also raised concerns about constitutional propriety from the third Governor General of Canada, appointed in 1872 by Gladstone’s government in the United Kingdom — Frederick Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (or Lord Dufferin or just Dufferin for short).

On October 27, 1873 Alexander Mackenzie, a dour Scots Baptist stonemason from Ontario, who had inherited the mantle of Liberal leadership from Edward Blake, moved a vote of “severe censure” against the Macdonald government in the Canadian House of Commons. When it became clear that Macdonald would not actually win the vote as he at first expected (in an age when neither political parties nor party discipline were as tightly organized and enforced as they later became), he announced the resignation of his government on November 5, 1873.

Following the conventions of Canada’s “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom,” Lord Dufferin asked Alexander Mackenzie to form a new government. And the first age of John A. Macdonald as prime minister of the Dominion of Canada came to an end.

* * * *

The growth of public knowledge about the Pacific Scandal over the spring, summer, and early fall of 1873 did not altogether becalm John A. Macdonald’s first government of the new confederation.

On May 3, 1873 Macdonald himself, acting as his own minister of justice, introduced a bill in the Canadian House of Commons for the creation of a North-West Mounted Police. The purpose was “to maintain law and order, and to be a visible symbol of Canadian sovereignty, in the newly acquired North-West Territories.” Officers would wear red coats, in the British imperial style, and, as later legend explained, “always get their man.”

The original official name of the later popularly christened “Mounties” was just North-West Mounted Police (or North West Mounted Police, as in the 1940 Hollywood movie starring Gary Cooper, which premiered in Regina, Saskatchewan). On an early 20th century surge of British imperial sentiment, the official name became Royal Northwest Mounted Police in 1904. It was changed again to Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1920, when a Dominion Police force organized in 1868 to protect politicians on Parliament Hill in Ottawa was merged with the RNWMP.

An even bigger achievement of 1873 may or may not have had something to do with the leisurely recuperation of John A. Macdonald on the red-sand beaches of the former Île Saint-Jean, over the summer of 1870.

Despite the 1864 conference in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island (with an 1871 population just over 94,000) had shied away from the confederation of 1867, understandably concerned about the fate of the least populous province in a federal experiment where the 1871 population of Ontario was 1.6 million and Quebec 1.2 million, and even New Brunswick had more than 285,000 people (while Nova Scotia had 387,800).

As very succinctly explained by “the first digital, multimedia history of Canada” in the age of the internet (A Country By Consent) : “Macdonald … tried to lure PEI into the union with various incentives, but it wasn’t until they were faced with a major financial crisis that the political leaders began to consider Macdonald’s offer … An ambitious railway-building plan had put the government into debt and created a banking crisis.”

It is not entirely true that in an April 1873 election “island voters had the option of accepting Confederation or having increased taxes. Not surprisingly, they chose Confederation.” In fact, a Liberal government that negotiated with Ottawa in February 1873 put a confederation proposal before voters in April. Conservatives led by James Pope also supported joining confederation, but claimed a somewhat better deal was still possible. Pope’s party won and did get a $25,500 increase in Ottawa’s annual subsidy. Prince Edward Island “officially joined Canada on July 1, 1873.” And, in a somewhat slippery sense, it does seem arguable that — until 1949 at any rate – it was the only province to join confederation by popular vote.

“O Canada, mon pays, mes amours”

The final autumn 1873 fall of John A. Macdonald’s first government of the new Dominion of Canada had been sadly foreshadowed by an unhappy spring 1873 private moment, in the old imperial metropolis.

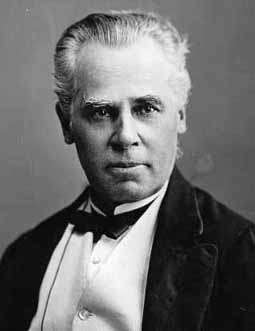

In 1871 the 19th century francophone Canadian lawyer from Montreal who had become Sir George-Étienne Cartier, 1st Baronet, PC, was diagnosed with a kidney ailment historically known as Bright’s Disease (now “described in modern medicine as acute or chronic nephritis”). After the 1872 election Cartier went to London, England, looking for a cure.

As explained by the present-day Wikipedia article on the subject : “His health did not improve and he died in London on May 20, 1873 at the age of 58. He was unable to pay a visit to his Manitoba riding where he was acclaimed a Member of Parliament [compliments in part of Louis Riel]. His body was brought back to Canada, and interred in the Cimetière Notre-Dame des neiges in Montreal.”

Cartier’s death — culminating with an “an elaborately solemn funeral in Montreal on June 13” — was especially hard on John A. Macdonald. Overcome by emotion, he could barely read a telegram announcing what had happened to the Canadian House of Commons in May.

Later in June Lord Dufferin reported on Prime Minister Macdonald to the colonial secretary in London : “Cartier’s funeral” was “too much for him,” Dufferin wrote. Macdonald had “been compelled to resort to more stimulants than suit his peculiar temperament … It is really tragical to see so superior a man subject to such a purely physical infirmity, against which he struggles with desperate courage, until fairly prostrated and broken down.”

* * * *

Especially in the 21st century, it is almost impossible not to wonder a little how Canadian history might have been different if George-Étienne Cartier (58 years) had lived as long as John A. Macdonald (76 years).

One side of Cartier did reflect Macdonald’s underlying conservatism and attachment to the 19th century British empire. He is said to have “been named in honour of King George III” — by an unusually upwardly mobile family of French Canadian grain merchants.

He is noted as well for his confederation-era declaration that :”The difference between our neighbours and ourselves is essential. The preservation of the monarchical principle will be the great feature of our confederation, whilst on the other side of the line the dominant power is the will of the masses, of the populace.”

(Though 1867 also saw the first publication of Walter Bagehot’s classic on The English Constitution — the same “Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom” prescribed in the British North America Act, 1867. Bagehot explained that even in the homeland of what would not too much later be called parliamentary democracy, on the Westminster model, the monarchy had already become part of the merely “dignified” as opposed to “efficient” part of the constitution. And : “There are indeed practical men who reject the dignified parts of Government.”)

* * * *

On other sides of his political personality, Cartier was different from Macdonald. And he stood for an at least somewhat if nonetheless quite seriously different Canadian future. As explained by the Canadian Encyclopedia, in his youth Cartier “composed the patriotic song ‘O Canada, mon pays, mes amours’ — perhaps the model for the later national anthem.” Macdonald’s ultimate patriotic boast would be : “A British subject I was born, a British subject I shall die.”

The full length and breadth of Cartier’s political career also illustrates a Canadian tendency to pragmatically blend ideological postures and principles. He began by fighting on the side of the rebels in the Lower Canadian rebellion of 1837–38, against the “Chateau Clique.” And in his early career in the United Province, he was Reform leader “Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine’s campaign manager and right-hand man.”

After 1848, he was first “elected as a Liberal Reformer in Verchères,” south and west of Montreal. (He did not move to Montreal East until 1861.) The Lower Canada Bleus he came to lead began as moderate Reform followers of LaFontaine. In many ways Cartier would remain closer to the Liberal side of the “Liberal Conservative” party.

As his symbiosis with the career of Louis Riel similarly suggests, George-Étienne Cartier was a resolute French-speaking Catholic from Quebec as well. And he wanted to see more room for his Canadien compatriots (including the mixed-race descendants of the old French and Indian fur trade) in the future growth of Canada, coast to coast to coast.

If George-Étienne Cartier had lived beyond 1873 and into the 1890s, like Macdonald, Louis Riel’s “postage-stamp” Province of Manitoba might have survived as a real-world vehicle of Red River Métis aspirations. Instead it finally became something much closer to what the Métis National Committee of 1869 feared, when Macdonald appointed William McDougall from the Anglo-American frontier in Ontario as first lieutenant governor of Canada’s new Northwest Territories.

Yet in the very end even Canadian history has many cunning passages. According to much more recent legends, when Pierre Elliott Trudeau first became prime minister of Canada in the middle of 1968 he moved not into John A. Macdonald’s old corner office in the East Block of the Ottawa Parliament Buildings, but into the adjacent office occupied by the first Minister of Militia and Defence, George-Étienne Cartier.

FROM

Children of the Global Village

Democracy in Canada Since 1497

Randall White

eastendbooks 2024

(For background on the larger series of which this is a part, see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic.)

PART III

DOMINION OF CANADA, 1867—1963

1

Blowing in the Wind … The Northwest Territories and Louis Riel’s Manitoba … Storm Troopers of the Tories (and Others) … Pacific Northwest : Salish, Tlingit, and Tsimshian … Pacific Scandal, Red Coats, Red Sand … “O Canada, mon pays, mes amours”