If American democracy is in trouble, so is democracy in Canada ..

Mar 30th, 2013 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

Harold Innis on the Peace River, 1924 – field work for his first local classic on The Fur Trade in Canada : An Introduction to Canadian Economic History.

“Great Britain, the United States and Canada” is the title of a now 65-year-old essay by Harold Innis, Canada’s pioneering great economic historian (and the godfather of Marshall McLuhan). As winter at last gives way to spring north of the North American Great Lakes, a few vaguely parallel thoughts about our time today have been brought to mind by four diverse items in the news of the past few weeks.

The first item – from a thematic if not strictly chronological standpoint – is an article by the British political scientist David Runciman, in the March 21, 2013 issue of the London Review of Books. As the print edition of this eminent publication notes, the article documents the recent occasion on which “David Runciman spoke about the crisis in American democracy at the second of this year’s LRB Winter Lectures” – in the still more or less magnificent old imperial metropolis across the sea.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper chats with British Prime Minister David Cameron during a family photo at the G20 Summit in Cannes, France. November 3, 2011. (Photo by Jason Ransom.)

At a time when even some Americans are coming to the conclusion that their democracy is in some sort of crisis, it is not surprising that a British political scientist would elaborate on the theme. Runciman begins by noting that : “During the early years of the American republic, in the first half of the 19th century, what fascinated outsiders was its sheer implausibility.” As an outsider in (say) the first quarter of the 21st century, Runciman goes on to discuss the various ways in which : “It is starting to look implausible again. Can you really do politics like this and expect it to last?”

Up here in the Canadian true north, strong and free, where we still follow the rather different British model of what has come to be known as parliamentary democracy, we might be inclined to read “How can it work? David Runciman on American democracy” with something of the smug self-satisfaction we so often (and inappropriately) bring to such discussions.

Harold Innis in fact nicely captured all this 65 years ago in “Great Britain, the United States and Canada.” And it is sobering to think that, in this respect at least, so little has changed since then: “A further evidence of political lethargy,” Innis wrote in 1948, “has appeared in an infinite capacity for self-congratulation. Invariably we remark on the superiority of Canadian institutions, Canadian character, and Canadians generally, over Americans. This, of course, is our common North American heritage but in Canada it appears to lead to little more than a congenital tendency toward long arms, with which we can slap our own backs. It is a commonplace …Â that we are encouraged in this by our polite friends from the United States and Great Britain.”

Lauren O’Nizzle, a young “super fan” of Harold Innis’s “Minerva’s Owl essay,” and many other remarkable things in Canada today.

At the same time, it also seems arguable that Canadian institutions (and Canadians generally) have made a little progress since the late 1940s. To look on American politics with any smug self-satisfaction in the spring of 2013 a Canadian has to be deeply attracted to the leadership of Stephen Harper and his new Conservative Party of Canada. Recent opinion polls suggest that barely a third (or less) of the Canada-wide electorate can qualify under this heading at the moment. Over the past week some further dissenting voices have apparently arisen within the tightly monitored corridors of power that structure PM Harper’s Conservative Party itself. And in my own small office, with a window that looks out on an only slightly larger urban North American backyard, I contemplate three other articles of the recent past, that also prompt me to wonder “How can it work?” as I think about Canadian democracy today : “55% of Canadians want change to Canadian head of state instead of continuing with any member of the British royal family” ; “Harper names Tannas to fill Alberta Senate vacancy” ; and “Liberal leadership: Martin Cauchon says Justin Trudeau outdated on approach to Quebec.”

1. “55% of Canadians want change to Canadian head of state instead of continuing with any member of the British royal family”

The new opnion poll which finds that “55% of Canadians want change to Canadian head of state instead of continuing with any member of the British royal family” was released this past March 18, by Duff Conacher’s admirable new group, “Your Canada, Your Constitution – Involving Canadians in their democracy.”

The exact question the poll asked was “Canada’s federal government, and the governments of the 15 other countries that have the British monarchy as their head of state, have agreed to change the rules about who in the royal family can inherit the throne in the future. Experts believe that in order to change these rules in Canada, the Constitution of Canada may have to be changed … If a change to the constitution will need to be made anyway, would you rather continue to have a member of the British Royal family as Canada’s head of state, or see a Canadian born person chosen by Canadians as Canada’s head of state?” There were three possible answers: “(a) Canadian born …Â (b) British Royal family …Â (c) Don’t know/refused.”

My own most immediate and visceral reaction to the poll’s finding that 55% of the 2,024 representative respondents Canada-wide chose “(a) Canadian born”, while only 34% chose “(b) British Royal family”, and 11% chose “(c) Don’t know/refused” is: How can it really be that as many as 34% still want to have the British Royal family as Canada’s head of state?

This statistic is even more distressing when you look at the regional breakdown. To start with here, Quebec (understandably, many will wisely enough observe) has 79% who want a Canadian head of state for Canada, and only13% for the British Royal family. Atlantic Canada and Ontario each have 49% Canadian and 39% British Royal family. Manitoba and Saskatchewan have 46% Canadian and 39% British Royal family. Alberta has 49% Canadian and 37% British Royal family. And British Columbia actually has (in this poll at any rate : students of such polls over the past decade will know this is not always the case) only 39% Canadian and 53% British Royal family. (And in all these cases the residual percentage after the Canadian and British Royal family numbers have been added is of course “Don’t know/refused.”)

On the one hand, consider these polling results alongside the almost pathologically strategic Stephen Harper’s apt enough short to mid term calculation that his Conservative Party can win a majority of seats in the Canadian House of Commons with less than 40% of the cross-Canada popular vote, overwhelmingly concentrated outside Quebec (and especially in Western Canada and Ontario outside Toronto). In this light you can start to appreciate the subtle cunning of his decision to revive such things as the name “Royal Canadian Navy,” and all that.

On the other hand, polls like this do after all continue to show that a cross-Canada majority, sensibly enough, already no longer supports the British Royal family as the (symbolic) Canadian head of state (whatever that may mean, when the Governor General nowadays appointed by Canadian not British prime ministers has exercised all the practical powers involved, more or less since the end of the Second World War). Ie, from a longer term point of view, it is reasonable to ask “How Can Canadian democracy [continue to] work?”, with the British monarch as its symbolic head of state? (And this point is underlined, when you look at the age-group breakdown for the YCYC’s latest poll: 18—24: 66% Canadian head of state ; 25—34: 60% Canadian ; 35—44: 56% Canadian ;Â 45—54 : 54% Canadian ; 55—64: 53% ; 65 + : 47%.)

2. “Harper names Tannas to fill Alberta Senate vacancy”

At the moment it is rather difficult to imagine just how the Canadian history of the future will judge the prime ministerial career of Stephen Harper – which will have lasted for (as some see it) as many as nine all too long years by the time of the next federal election in 2015.

His one undeniable achievement, it seems clear enough, will be to have brought Western Canada into the real corridors of federal power in Ottawa at last. Yet his shorter term efforts to revive the now increasingly archaic and obsolete traditions of the British monarchy in Canada – in an effort to stiffen the support of the strategic minority of the Canadian electorate, on which his clever electoral calculations rest – already highlight his limitations in the kind of post-colonial nation building that the Canadian future still (almost desperately?) needs.

At the same time again, PM Harper has at least kept a kind of half-faith with the one nation-building objective that has, so to speak, distinguished and even elevated the Western Canadian regional quest for real power at last, at the centre of the continually evolving Canadian confederation of 1867, from sea to sea to sea.

New Alberta Senator Doug Black. Nothing ever comes up roses all the time. As Sun News reported this past September: “In 18 months as chair of the University of Calgary's board of governors, Doug Black – elected as a Tory senator in waiting in April – filed $28,030.88 worth of expense claims ... That's a whopping 64 times what his predecessor claimed – in less than half the time.” He’ll probably feel at home in the still unreformed Senate of Canada. DAN ILIKA/QMI AGENCY.

Back when he first came to office in 2006, Mr. Harper was still talking about the unreformed Senate of Canada (still modelled too much on the historic British House of Lords) as “a relic of the 19th century.” He has gone on to indulge in a veritable orgy of the kind of unreformed prime ministerial Senate appointments he once swore he would never stoop to. Yet he also still has a bill that at least begins a process of “step by step” Senate reform in Canada waiting in the wings of parliament as it were. (Or, more exactly perhaps, now waiting for a judgment on its constitutionality from the Supreme Court of Canada, at Mr. Harper’s request.)

Moreover, in keeping with the principles of his Senate reform bill, PM Harper has managed to arrange that at least Alberta (where the modern Western Canadian quest for Senate reform has its symbolic heartland) now has two de facto democratically elected senators.

As explained by no less than cbcnews.ca, this past March 25: “Prime Minister Stephen Harper has named Scott Tannas to fill the Senate seat vacated by Bert Brown, who retired last Friday. Tannas, who is president and CEO of Western Financial Group, finished second in Alberta’s senate elections conducted during last April’s provincial election … A statement from the Prime Minister’s Office Monday announcing the appointment said Tannas supports the Conservative government’s reform plans for the Senate, including legislation to limit term lengths for senators and encouraging provinces to hold elections to nominate future appointees … Doug Black, a Calgary lawyer and the chairman of the University of Calgary’s board of governors, received the most votes for nominees to be senators in waiting and was appointed to the Senate in January to replace Liberal Joyce Fairbairn, who retired early for health reasons.”

3. “Liberal leadership: Martin Cauchon says Justin Trudeau outdated on approach to Quebec”

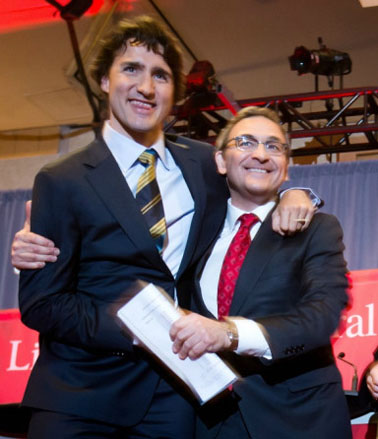

Justin Trudeaum (l) and Martin Cauchon (r) embrace after the Liberal party's first leadership debate in Vancouver, Sunday, January 20, 2013.

Another of Stephen Harper’s all too ambiguous contributions to the kind of nation building that the Canadian future still needs was his strategic engineering of the late November 2006 declaration by the Canadian House of Commons that the Quebecois constitute a nation within a united Canada.

This uniquely Canadian concept, it seems clear enough, has proved not all that popular (to say the least) among the strategic Western Canadian and “rural Ontario” minority political base, on which the fortunes of the current Harper Conservatives depend. And the fact that PM Harper has drawn back more than a little from its implications is arguably another blot on his record as a potential Canadian nation builder – in an era where the real need for some kind of final stage in what the constitutional law professor Brian Slattery has called “the long process of decolonization that Canada has undergone since 1867” has become almost palpable.

At the same time, as Joan Bryden at the Canadian Press has explained in an article yesterday, March 29, 2013: “Justin Trudeau may be the youngest, hippest Liberal leadership contender but, when it comes to Quebec, rival Martin Cauchon says the front-runner is a relic of the past … Trudeau has scoffed at suggestions that attempts must be made to finally secure Quebec’s signature on the Constitution – patriated by his father, Pierre Trudeau, in 1982 over the objections of the province’s separatist government … While that was the right answer during the 1980s and 1990s, when Canadians were fed up with interminable constitutional wrangling, Cauchon says it’s no longer good enough … Trudeau’s response to the national unity question amounts to ‘the good old answers that people used to give’ in the wake of failed constitutional negotiations, Cauchon told The Canadian Press during an interview … ‘Now it’s not the time to go back with those, I would say, empty answers that a lot of people have been using in the past … I say it’s time, actually, to have a closer look at the situation.’”

You don’t have to understand what this actually means to appreciate that bad news of this sort for Justin Trudeau arguably enough amounts to good news for Stephen Harper. What I think it means myself is that – along with the contemporary domestic nation-building themes of Senate reform and the quest for a Canadian head of state (and, no doubt, something about the role of the aboriginal peoples of Canada too) – we need to be more seriously contemplating just what the Quebecois nation in a united Canada means practically. Thomas Mulcair and the federal NDP have arguably come a little closer to fulfilling this need for the Canadian future, than either the Harper Conservatives or the (still, strictly speaking, potential) Trudeau Jr. Liberals. But among all parties and leaders in 2013 the failure to deal constructively with all of the head of state issue, Senate reform, aboriginal rights, and Quebec’s role in the confederation of tomorrow still constitutes what Harold Innis would call “further evidence of political lethargy” in Canada today – following the ancient lamentable traditions he wrote about 65 years ago!

4. Why isn’t David Runciman more impressed by the re-election of President Obama?

The one most critical thing I feel myself about “How can it work? David Runciman on American democracy” turns around its failure to acknowledge the vastly positive slant on the American future symbolized by the re-election of Barack Obama last fall. And this may be something that is simply much more striking when you live right next door to democracy in America, as opposed to across the sea. (Even if you do live across the sea in an old “mother country” that ostensibly speaks the same language as the great majority in the American Republic.)

Runciman comes at least somewhat close to all this, when he writes such things as : “Take Obama’s re-election. It isn’t hard to weave it into a recovery narrative …” But he finally ends on a less optimistic note – “American democracy may be trapped by its record of success.” My own feeling is that it is much closer to some deepest truth to emphasize the extent to which it really “isn’t hard to weave” Barack Obama’s re-election “into a recovery narrative.”

It wasn’t that long ago that the great vain progressive hope in American politics was “Run Jesse Run,” set beside the incontestable truth that no kind of black man (even one who’s mother was white) could ever become president of the USA. Much more recently, the greatest objective of Obama’s most retrograde Republican opponents was to confine him to a one-term presidency. And, whatever else, they have undeniably failed in this! To me Runciman underrates the extent to which the re-election of Barack Obama presages the beginning of a new era in the history of American democracy, with a more diverse demographic base, and a more realistic agenda for American success (which is not the same as the always unrealistic national goal of “supremacy”) in a rapidly changing (and in most ways for the better) global village.

In this same kind of universe I believe that what Harold Innis called the tradition of Canadian “political lethargy” will at least abate long enough to deal in some workable way with all of the head of state issue, Senate reform, aboriginal rights, and Quebec’s role in the confederation of tomorrow – now that Stephen Harper has at least and at last brought Western Canada into the corridors of power in Ottawa.

David Runciman hints at the real-world alternative, it seems to me at any rate, when he speculates that, in the year 2072 : “Perhaps, instead of Texas leaving, Mexico will have joined.” If something of this sort does prove true about the longest term future, it seems more than likely that Canada will have joined a few decades or, at the very least, a few years earlier. (And it is interesting, in some ways, that “How can it work? David Runciman on American democracy” makes no reference to Canada at all.)

Harold Innis (l), Hans Seyle (c), and Alf Earling Porsild (r) on a visit to the Soviet Union, just after the end of the Second World War in 1945.

In Canada, it seems to me right now at any rate, we have perhaps another generation (say to 2045) to put ourselves on more solid “national” foundations (in a political and certainly bilingual and multiracial but of course not in any ethnic or narrowly cultural sense). Strangely enough (perhaps again), the 2012 victory of Barack Obama in the United States seems to have strengthened my belief that, when all is said and done, the Canadian people will finally decide to carry on with the distinctive “free and democratic” future they have been oh-so-gradually and quietly building over the past 146 years. And the parallel future of the American giant next door will similarly prove more resilient and attractive than David Runciman currently seems to fear.