Indian Election I : Democracy in India could prove just as troubling as Democracy in America in 2024

Mar 26th, 2024 | By Counterweights Editors | Category: In BriefCOUNTERWEIGHTS EDITORS, GANATSEKWYAGON, ON, CANADA. TUESDAY, MARCH 26, 2024. We now know that : “General elections will be held in India from 19 April 2024 to 1 June 2024 to elect the 543 members of the 18th Lok Sabha. The elections will be held in seven phases and the results will be announced on 4 June 2024.”

The Wikipedia article goes on : “This will be the largest-ever election in the world … Prime Minister Narendra Modi will be contesting … for a third consecutive term … Approximately 960 million … individuals out of a population of 1.4 billion are eligible to participate.”

India and Canada today : one roadmap to a Canadian republic?

This 2024 election in India has some particular interest for Canada — which shares with India what Canada’s Constitution Act, 1867 calls “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.”

(The Lok Sabha or “House of the People,” eg, is the lower popularly elected house of India’s parliament, equivalent to the Canadian House of Commons. And Narendra Modi is the leader of the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] — the political party with the largest number of seats in the current 17th Lok Sabha.)

In particular again India today offers Canada one instructive model with regard to such key current headlines as “Support for King Charles wanes as Canadians’ republican sentiment grows … Growing numbers of Canadians want an elected head of state, survey reveals.”

India provides a model of “a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom” that does not have the British (or any other) monarch as head of state.

The republican head of state in India (somewhat misleadingly called a President, from Canada’s point of view?) is indirectly elected by the members of federal and state (provincial in Canada’s case) legislatures.

(Ireland offers another model, with a directly or popularly elected ceremonial head of state in a parliamentary democracy. The holder of this office is also called a President, but without the day-to-day governing power of the Prime Minister. The president in such cases has a role more like the monarch’s role in the UK — or in practice the Governor General of (once upon a time) Ireland, India and (still now in 2024) Canada, Jamaica, Australia, New Zealand, and so forth.)

Democracy in India in the global village today

From a broader and no doubt more important standpoint, the 2024 general election in India (which will start somewhat less than four weeks from now) arguably has implications for the great cause of democracy in the global village almost (or even just?) as weighty as those of the later US presidential (and congressional) election on November 5, 2024.

These implications flow from the designs of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party.

(Just to start with, “Bharat” is the ancient Sanskrit name for “India.” And see this intriguing piece from Al Jazeera : “India or Bharat: What’s behind the dispute over the country’s name? … A change to the Sanskrit name is backed by PM Narendra Modi’s BJP, which says the word ‘India’ is a symbol of colonial slavery.”)

Narendra Modi first became Prime Minister of India in the election of 2014 (again starting in April and this time ending in May).

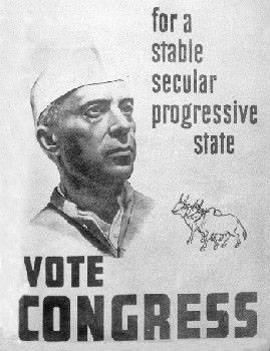

During the past 10 years two successive governments led by Mr. Modi’s right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party have done a lot to crystalize some long-simmering Hindu nationalist alternative to the “stable, secular, progressive state” envisioned by the Congress party (and accompanying Indian National Congress movement), that did so much to create the modern independent Republic of India — before and finally just after the Second World War.

(Or, to cite the still striking language in the Preamble to the 1950 Constitution, first moved in the late 1940s Constituent Assembly by Indian National Congress leader Jawaharlal Nehru : “WE, THE PEOPLE OF INDIA having solemnly resolved to constitute India into a SOVEREIGN SOCIALIST SECULAR DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC and to secure to all its citizens …”)

“The era of this kind of entitlement is now over under PM Narendra Modi”

As far as socialist goes in this formula, Mr. Modi’s two governments so far have been resolutely capitalist on economic development grounds.

Some might say as well that on at least some economic understandings of the term PM Modi has been more “progressive” than the Congress party today. (Which forms the main and still strongest party in opposition to Narendra Modi’s aggressively right-wing regime.)

As far as secular goes, Mr. Modi’s governments have also presided over what seem from a distance like strong efforts to increase public emphasis on the Hindu religion (and its broader cultural reach), that does still unite more than three-quarters of the Indian population.

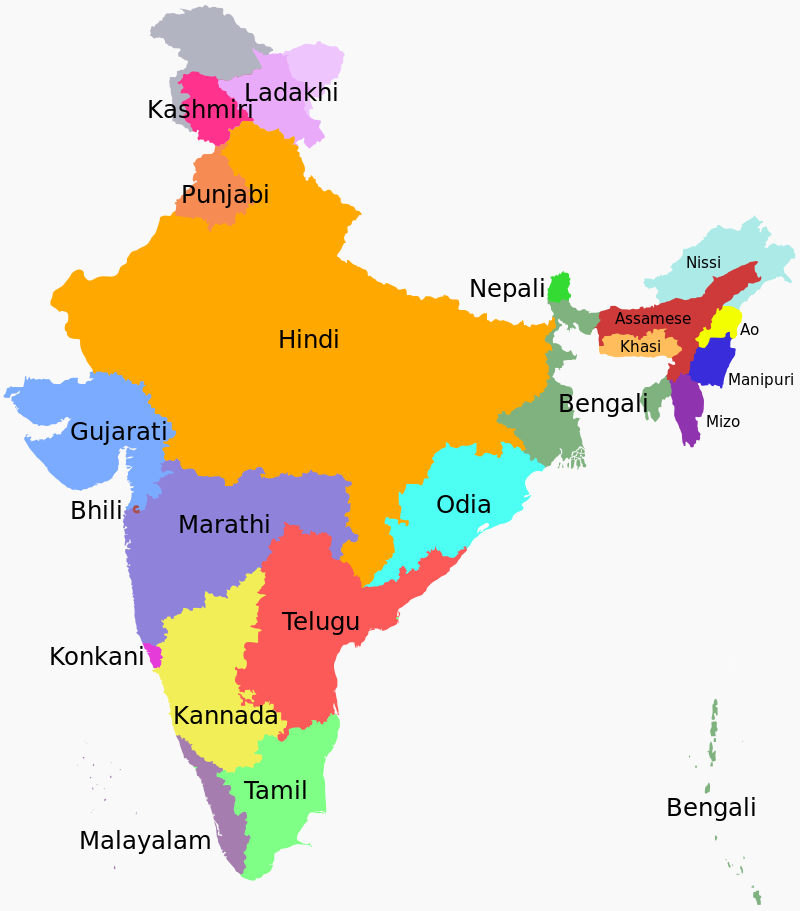

(At the same time, Hindi as a language is not the mother tongue or even first language of a majority of the wider Indian community. In this respect India remains “more like Europe” than any single country — though with a big Hindi-speaking region in the middle north.)

Finally (for now), we remain particularly concerned, as friendly offshore admirers of the world’s largest democracy (or worse), by two recent events in, as it were, the build-up to the Indian election that will start this coming April 19, 2024.

The first is last year’s sentence of Congress party leader Rahul Gandhi to two years’ imprisonment for some intemperate criticism of PM Modi. (Admirably enough, Mr. Ghandi’s conviction was subsequently suspended by the Supreme Court of India.)

Our second annoying offshore democratic fan’s concern is about last month’s government freezing of the opposition Congress party bank account.

And we’re not comforted by such explanations as : “BJP national spokesperson Sambit Patra said, ‘As far as bank account freezing is concerned if you are a defaulter, you will be treated like one. The sense of entitlement that the Gandhi family had that even if we were a defaulter, provisions of the law of this country would not apply to us. The era of this kind of entitlement is now over under PM Narendra Modi.’”

In any case if the recent polling is any guide PM Narendra Modi’s BJP and the wider “National Democratic Alliance” it leads will almost certainly win a comfortable enough third consecutive term in office, when the final results of the 2024 Indian election are announced this coming June 4.

Even so, because Indian politics right now still seems so intriguing and important to us, this will be only the first of several notes we’ll offer on the subject — the Indian election 2024, as intermittently viewed by a fascinated if at best half-informed group at the office in the faraway urban wilderness of Southern Ontario, north of the Great Lakes in Canada … through the latest new lens of the world-wide web …