William & Catherine’s tone-deaf trip to the Commonwealth Caribbean (and the myth of “Canada is just America with monarchy US abandoned long ago”)

Mar 30th, 2022 | By Randall White | Category: In BriefONTARIO TONITE. RANDALL WHITE, FERNWOOD PARK, TORONTO, 30 MARCH 2022. Strictly by accident, I was in Richmond, Virginia at the time of the wedding of the mother and father of the William who just recently completed “an eight-day tour of Belize, Jamaica and the Bahamas during which he and wife Kate were celebrated but also criticized as being ‘tone deaf’ for perpetuating images of Britain’s colonial rule” (Associated Press).

As a still younger Canadian back then I was surprised by all the attention paid to the “Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer” on July 29, 1981 in the Richmond media.

I thought this is the USA. Americans are not interested in the British monarchy. More fuss was being made about this royal wedding in Richmond, Virginia, it almost seemed, than in my Toronto hometown (known in the 1930s as “the citadel of British sentiment in America”).

I subsequently stumbled across some tourism literature promoting Virginia as a homeland of “The English Heritage in America.” I doubt anyone is still using this slogan in 2022. But back then it helped me understand why Richmond, the capital of Virginia, was so interested in the Charles and Diana wedding. Even so, my time down south in the summer of 1981 did adjust my impressions about the broader popularity of the anglophone monarchy in the USA.

William and Catherine in the Caribbean 2022

Back at the royal Caribbean tour in late March 2022 in Jamaica (the Associated Press goes on) : “Prime Minister Andrew Holness told the royals his country intended to become a republic, removing the British monarch as its head of state.”

At the end of the tour Prince William told an audience in Nassau, capital of the Bahamas : “We support with pride and respect your decisions about your future … Relationships evolve. Friendship endures.”

The Associated Press report concludes with : “Whatever the former colonies decide about their continuing relationship with the crown, William said he wanted to continue serving them through the Commonwealth, a voluntary association of 54 countries with historical links to Britain. The Queen has been head of the Commonwealth throughout her reign and Prince Charles, William’s father, is her designated successor … William recognized that he may not follow in their footsteps … ‘Who the Commonwealth chooses to lead its family in the future isn’t what is on my mind’.”

As it happens in the 21st century, although the remarkably long-lived Queen Elizabeth II is head of the Commonwealth, she is not also the theoretical head of state of each of the 54 Commonwealth members. (As Queen Victoria was at the height of the old British empire.)

India led the way here when on January 26, 1950 it became a republic altogether separate from the United Kingdom (like the new Republic of Ireland), with an Indian president instead of the British monarch as head of state. But the new republican India also remained in the Commonwealth of Nations (the heir of the old British empire).

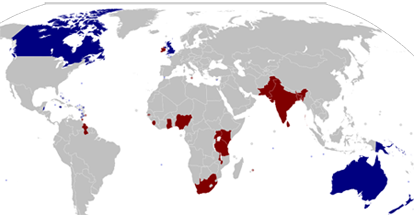

Today only the United Kingdom and 14 other so-called “Commonwealth realms” (Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu) are still members of the Commonwealth who also recognize the British monarch as head of state.

Even here, as already noted, the Prime Minister of Jamaica has just told William and Catherine that his country intends “to become a republic, removing the British monarch as its head of state” in the near enough future. And in some bubbling corners of the true north, strong and free, this prompts a second look at an Angus Reid Institute polling report from late this past November.

Angus Reid on the monarchy in Canada November 2021

The Angus Reid report was inspired in part by the recent “island nation of Barbados … making a big change by becoming a republic.” And it is entitled : “For many Canadians, interest in remaining a constitutional monarchy will die with Queen Elizabeth … Most say they’ll be saddened by death of Queen, but don’t wish to continue with monarchy under Charles.”

The main question asked by the poll here was : “Regardless of what you think about individual members of the royal family, do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come?”

In the “online survey from Nov. 26-29, 2021 among a representative randomized sample of 1,898 Canadian adults who are members of Angus Reid Forum” the broadest result was that only 25% answered YES to this question, Canada wide. And 52% were prepared to say a definitive democratic majority NO. (While a very Canadian 23% opted for “Not sure.”)

There are intriguing regional variations in this broad Canada-wide answer to “do you think Canada should continue as a constitutional monarchy for generations to come?” Here as elsewhere the strongest difference is between Quebec and the rest of Canada. The NO vote is not surprisingly much stronger in Canada’s francophone-majority province.

Without Quebec (72%) the NO vote fades to only close to but not quite a majority (Alberta 49%, Saskatchewan 47%, BC and Ontario 46% each, and so forth.) And the YES vote goes as high as 31% in Alberta, 35% in Atlantic Canada, and 38% in Manitoba!

There are other intriguing variations in the Angus Reid report. But the answer the Canada-wide majority gives on the future of the monarchy after the present much-admired Queen is decisive. The poll also asked the question “Would you support or oppose Canada recognizing her heir, Prince Charles, as King, by swearing oaths to him, putting him on currency, and recognizing

him as Canada’s official head of state?”

Only 9% Canada-wide would strongly support Prince Charles as King of Canada, with a somewhat more robust 25% saying they would moderately support such a fate. Meanwhile 26% would moderately oppose and 40% strongly oppose any future King Charles. A virtual two-thirds majority of 66% generally oppose carrying on with the monarchy after the sad passing of the present much-admired Queen (especially admired by female Canadians).

“What could a Canadian republic look like?”

It’s at this point that I personally find the late November 2021 Angus Reid report somewhat alarming. Midway through its text it asks “What could a Canadian republic look like?”. And the various options it offers its representative randomized sample of 1,898 Canadian adults strike me as disturbingly unrealistic.

I at least detect some vague sense among more than a few Canadians in 2022 that there is something useful which works about our present system of government (granting much else needs change), and this is worth hanging onto for the next human adventures that lie ahead.

But as the Angus Reid polling does make clear enough, it is not the British monarchy that Canada will be retaining politically for generations to come (and that will continue to help distinguish it from the friendly giant next door). It is British-style — or as today’s at once more broad and narrow lexicon has it “Westminster” — parliamentary democracy.

This kind of democracy is, no doubt, an invention of the same 19th century British empire which boasted it was a global political creation “on which the sun never dared to set,” but nonetheless did appalling things. (African slavery in the so-called New World is probably the most appalling but far from only example.) Yet the greatest surviving legacy of all this today is also the world’s largest democracy in the modern Republic of India — the second (and soon-to-be first?) most populous country in the world.

Learning from Indian (German) and Irish (Icelandic) history in Canada today

The process by which India became a parliamentary democratic republic that remained in the Commonwealth, like the parallel one by which Ireland became a similar kind of republic that did not, is part of the Commonwealth political history Canada shares with the other 54 members.

And as both cases show, turning the governor general of the old monarchy into the president of the new republic is the easiest and least unsettling way of politely waving goodbye to Prince Charles as Canadian head of state — as 66% of Angus Reid’s Canadians already want to do.

The only question that remains is how to democratically reform the selection method for the new parliamentary democratic head of state. Having the Canadian prime minister appoint the Canadian governor general, as at present, is a little too “authoritarian” for the 21st century.

Here again India (like today’s German parliamentary democratic republic outside the Commonwealth) provides one alternative — indirect election by federal and state (or provincial) legislatures. Ireland (and Iceland outside the magic Westminster circle) provides another — direct election by the adult voting population.

Somehow we need to start talking about this kind of Indian and Irish and related parliamentary democratic political history in Canada. Those of us who harbour republican sentiments need to start debating this remaining key issue of the best practical republican alternative for Canada.

And somehow in this kind of debate all 10 provincial legislatures will eventually be convinced about the need to amend the Constitution of Canada (as required by the Constitution Act, 1982), to conform with the will of the democratic majority of all Canadians (now at 66%), who already oppose carrying on with the monarchy after the passing of the much-admired Queen.