News from Nunavut : what does the Mayer report tell us about Canada’s Arctic experiment?

Jun 17th, 2007 | By L. Frank Bunting | Category: Canadian Provinces Whatever else, Canada does have a vast chunk of northern geography. And both climate change and new resource technologies seem to hold out fresh prospects for far northern economic development that more southerly business interests can applaud. The eastern Arctic is also now home to the innovative Nunavut Territory – whose creation in 1999 still stands as one of the most imaginative acts in the recent history of the Canadian federal government.

Whatever else, Canada does have a vast chunk of northern geography. And both climate change and new resource technologies seem to hold out fresh prospects for far northern economic development that more southerly business interests can applaud. The eastern Arctic is also now home to the innovative Nunavut Territory – whose creation in 1999 still stands as one of the most imaginative acts in the recent history of the Canadian federal government.

A report by Montreal lawyer Paul Mayer has raised some poignant questions about how this remarkable if sometimes troubled experiment is progressing. To add to the intrigue this year’s Western Premiers’ Conference will be held July 4-6 in Nunavut’s largest town of Iqaluit. It is time to forget the latest sophomoric antics in the deep south of Ottawa for a moment, and ponder how the future looks this summer in the land of the midnight sun.

Some quick historical background …

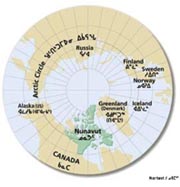

In the beginning – after Ottawa had purchased the old Hudson’s Bay Company lands in the immediate wake of the 1867 confederation – there was just the Northwest Territories. Then the more southerly parts of this vast region became the modern provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta (as well as the northern parts of present-day Ontario and Quebec).

In the beginning – after Ottawa had purchased the old Hudson’s Bay Company lands in the immediate wake of the 1867 confederation – there was just the Northwest Territories. Then the more southerly parts of this vast region became the modern provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta (as well as the northern parts of present-day Ontario and Quebec).

Then the federal government created a separate Yukon Territory in the remaining far northern Northwest Territories, to better control the Klondike Gold Rush of the late 19th century. For almost all the 20th century Canada had two northern territories – the Yukon and N.W.T.

Then the late 20th century constitutional project started by Quebec – then joined by such various other Canadians as the aboriginal peoples of Canada, Western Senate reformers, and on and on (and given its initial ground floor by Pierre Trudeau’s Constitution Act 1982) – raised the prospect of creating what amounts to a new Inuit territory in the eastern region of N.W.T.

Then the late 20th century constitutional project started by Quebec – then joined by such various other Canadians as the aboriginal peoples of Canada, Western Senate reformers, and on and on (and given its initial ground floor by Pierre Trudeau’s Constitution Act 1982) – raised the prospect of creating what amounts to a new Inuit territory in the eastern region of N.W.T.

With the official establishment of Nunavut in 1999, some would say, the federal government effectively gave the Inuit of the far north at least the bare beginnings of something somewhat like what many Quebecois were asking for in the south. (Or others might perhaps urge, something more or less like what the French-speaking majority in Quebec has virtually had since the middle of the 19th century in any case.)

As explained by the excellent 1987 first volume of the Historical Atlas of Canada, the exact traditions of today’s Inuit (once called Eskimos) only go back some 400 years. It is “not known when the ancestors of the Paleo-Eskimos crossed from Asia to Alaska.” But: “About 4000 years ago a Paleo-Eskimo people, the Pre-Dorset, expanded rapidly eastward across Arctic Canada from Alaska.” This led to a so-called “Dorset culture” that “depended on caribou, muskoxen, and fish … ringed seals and other sea mammals.”

As explained by the excellent 1987 first volume of the Historical Atlas of Canada, the exact traditions of today’s Inuit (once called Eskimos) only go back some 400 years. It is “not known when the ancestors of the Paleo-Eskimos crossed from Asia to Alaska.” But: “About 4000 years ago a Paleo-Eskimo people, the Pre-Dorset, expanded rapidly eastward across Arctic Canada from Alaska.” This led to a so-called “Dorset culture” that “depended on caribou, muskoxen, and fish … ringed seals and other sea mammals.”

Then: “By about AD 1000 the Thule people of northern Alaska,” who had developed new technologies for “the efficient hunting of bowhead whales,” using kayak and umiak boats and “harpoons attached to floats,” started to move east. Soon enough they had “occupied most of Arctic Canada,” and largely absorbed and supplanted “their Dorset predecessors.” Further changes, prompted by “climatic deterioration,” led to the culture of the historic Inuit, “after about AD 1600.” This included winters spent in coastal areas, living “in snow houses, often on the sea ice,” and hunting “ringed seals.”

The 20th century brought another wave of vast and unsettling change to life in far northern Canada. It is no longer possible for the Inuit to live in snow houses and feed themselves by hunting ringed seals. The highest motivation behind the creation of the Nunavut Territory in 1999 was to give the Inuit a new regional political structure inside Canada, that can help them mobilize today’s fresh northern resource development prospects to carve out a new life for themselves in the 21st century.

The 20th century brought another wave of vast and unsettling change to life in far northern Canada. It is no longer possible for the Inuit to live in snow houses and feed themselves by hunting ringed seals. The highest motivation behind the creation of the Nunavut Territory in 1999 was to give the Inuit a new regional political structure inside Canada, that can help them mobilize today’s fresh northern resource development prospects to carve out a new life for themselves in the 21st century.

In the 2001 Census there were 26,745 people in Nunavut – of whom 22,560 identified themselves as Inuit, 3,945 as non_aboriginal, 95 as First Nations or North American “Indian,” and 50 as Mtis or mixed race. The crucial issue explored in the just-released Mayer report is just how quickly the new territorial government elected by the overwhelming Inuit democratic majority in Nunavut should gain full control over resource development in its territory – just like an ordinary Canadian provincial government down south.

A very quick summary of Paul Mayer’s report …

A Canadian news- in-brief item in the Halifax Chronicle-Herald gives a very economical summary of the Mayer report:

A Canadian news- in-brief item in the Halifax Chronicle-Herald gives a very economical summary of the Mayer report:

“Despite Nunavut’s push for province-like powers over its resources, the Arctic territory is still not ready to take over from the federal government, says a report commissioned by Indian Affairs Minister Jim Prentice … The territory faces challenges ranging from social problems to economic development, but its biggest problem remains a shortage of trained people, says Paul Mayer, the Montreal lawyer who wrote the report.”

In Mayer’s own words: “The most significant challenge will be to ensure that the [government of Nunavut] has the human resources it needs to be fully ready and capable to honour its devolved responsibilities. If this issue cannot be satisfactorily dealt with, then the right conditions will not be in place to transfer federal responsibilities.”

In Mayer’s own words: “The most significant challenge will be to ensure that the [government of Nunavut] has the human resources it needs to be fully ready and capable to honour its devolved responsibilities. If this issue cannot be satisfactorily dealt with, then the right conditions will not be in place to transfer federal responsibilities.”

The Chronicle-Herald summary concludes with: “Nunavut Premier Paul Okalik welcomed the report as a necessary step in negotiations with Ottawa to gain control over the territory’s increasingly valuable – and accessible – natural resources. Those include metals from gold to uranium to iron, and diamonds, oil and natural gas … But Okalik said … he was disappointed Mayer didn’t give Nunavut credit for its achievements, which include educating its first Inuit lawyers, nurses and teachers.”

Additional troubling nuances and details …

A more elaborate piece on the Mayer report by Jim Bell, in the Nunatsiaq News out of Iqaluit, fleshes the story out at greater length:

A more elaborate piece on the Mayer report by Jim Bell, in the Nunatsiaq News out of Iqaluit, fleshes the story out at greater length:

“Canada should adopt a careful, step-by-step approach to the devolution of new responsibilities to the Government of Nunavut, says a report issued June 12 by Paul Mayer, the federal government’s ministerial representative for Nunavut devolution … Mayer began work on the report in November 2006, when Jim Prentice, the northern affairs minister, appointed him to study the idea of negotiating a devolution agreement with Nunavut.

“Such a deal would give big new powers to the GN: the power to manage public lands and natural resources, with a share of royalty money generated by oil, gas and mineral production … Mayer suggests this will not occur soon … But he said in an interview that an agreement-in-principle on devolution may still be possible by 2008 and that a final agreement by 2011 or 2012 is still doable’ if the two sides can agree on a negotiating process and what issues ought to be on the table.”

“Such a deal would give big new powers to the GN: the power to manage public lands and natural resources, with a share of royalty money generated by oil, gas and mineral production … Mayer suggests this will not occur soon … But he said in an interview that an agreement-in-principle on devolution may still be possible by 2008 and that a final agreement by 2011 or 2012 is still doable’ if the two sides can agree on a negotiating process and what issues ought to be on the table.”

Again, according to Mayer, “the biggest problem that Canada and Nunavut must tackle is Nunavut’s shortage of skilled professionals, which damages the quality of governance in the territory … Bluntly said, if this issue cannot be satisfactorily dealt with, then the right conditions will not be in place to transfer federal responsibilities,’ Mayer said.

“Mayer found that the GN already has trouble handling its current responsibilities, raising the question of whether Nunavut is ready to take on more … In light of the significant challenges identified in this report that the GN faces in assuming its current responsibilities, the easy answer would be no,’ Mayer says … But he also says that answer is unnacceptable, because devolution is a top priority for the Nunavut government and enjoys widespread political support.”

“Mayer found that the GN already has trouble handling its current responsibilities, raising the question of whether Nunavut is ready to take on more … In light of the significant challenges identified in this report that the GN faces in assuming its current responsibilities, the easy answer would be no,’ Mayer says … But he also says that answer is unnacceptable, because devolution is a top priority for the Nunavut government and enjoys widespread political support.”

Mayer “points out that the federal government, under Paul Martin’s Liberal government, committed itself to a devolution agreement with Nunavut in December of 2004, and that Stephen Harper’s Tory government continued that commitment in repeated statements … In fact, the devolution train left the station in December 2004,’ Mayer said …

“Mayer went on to say that many conditions are in place to begin devolution negotiations.’For example, unlike the Northwest Territories, Nunavut has only one land claim agreement, one aboriginal people, and one land claim settlement area, simplifying the process.”

“Mayer went on to say that many conditions are in place to begin devolution negotiations.’For example, unlike the Northwest Territories, Nunavut has only one land claim agreement, one aboriginal people, and one land claim settlement area, simplifying the process.”

At the same time: “In looking at Nunavut’s ability to handle more responsibility, Mayer pulls no punches … In discussing Nunavut society, he lists many of the well-known social ills … high crime rates, widespread substance abuse, family violence, poor health status and overcrowded housing … He says Nunavut’s education system must do a better job: An appropriate education system is essential to the success of Nunavut. The one now in place is currently failing’ … As for the quality of government, he said Nunavut faces a significant governance challenge,’ mostly created by high staff turnover and numerous unfilled jobs.”

The Nunatsiaq News also concludes with some reaction from Nunavut Premier Paul Okalik. He “does not like” some “sections of the report.” But “he said he remains optimistic’ and is willing to work with Jim Prentice to move the devolution process into actual negotiations … I don’t necessarily agree with all the contents of that report, but I must say it’s a start and I look forward to good discussions with Minister Prentice and his government,’ Okalik said.”

The Nunatsiaq News also concludes with some reaction from Nunavut Premier Paul Okalik. He “does not like” some “sections of the report.” But “he said he remains optimistic’ and is willing to work with Jim Prentice to move the devolution process into actual negotiations … I don’t necessarily agree with all the contents of that report, but I must say it’s a start and I look forward to good discussions with Minister Prentice and his government,’ Okalik said.”

Premier Okalik similarly “said Mayer’s characterization of Nunavut’s education system is unfair … We are seeing record numbers of Inuit graduating from our high schools. There’s no mention of that in the report. We’re developing the expertise and with time, it will be there.'” But Okalik “doesn’t necessarily disagree’ with the idea of a phased approach to devolution, pointing out that some government services were contracted back from the NWT until 2001, and that a similar approach could be used in devolving land and resource management.”

The premier has noted as well that: “Right now, the federal government is unwilling to include Nunavut’s lucrative seabed resources in devolution talks.” But “Okalik insisted that they must be included, and he said that giving those resources to Nunavut would strengthen Canadian sovereignty in the High Arctic … We want to do our part to ensure that we assert Canadian sovereignty in our waters.'”

The Nunatsiaq News item closes with: “It’s expected that Prentice will study the report, then decide when and how to move forward on Nunavut devolution.”

Where will the Harper government go from here?

A cynic might say that the Montreal lawyer Paul Mayer’s report just reflects the southern (and non-aboriginal) business community’s continuing lack of faith in the capacity of the new Inuit-dominated Nunavut Government to provide the kind of legal and institutional framework necessary for dynamic new resource development in its part of Canada’s far north.

A cynic might say that the Montreal lawyer Paul Mayer’s report just reflects the southern (and non-aboriginal) business community’s continuing lack of faith in the capacity of the new Inuit-dominated Nunavut Government to provide the kind of legal and institutional framework necessary for dynamic new resource development in its part of Canada’s far north.

(And without some significant development of this sort, the last number of years also seem to have made clear enough, there will not be the kind of economic base in Nunavut that can give the Inuit any serious hope of carving out a workable new life for themselves in the 21st century.)

What Mr. Mayer is clearly telling Minister Prentice is that the process of devolving full responsibility for its own resources on to the Nunavut government cannot move too quickly, if any satisfactory end result is to be achieved. If the Inuit are going to realize the future economic potential of their territory in the 21st century, they are going to have to learn more about working effectively with the southern non-aboriginal business interests, who will inevitably be playing a big role in developing the resources. At the same time the process cannot be drawn out indefinitely, in the interests of achieving some impossible nirvana. Because, as Mr. Mayer has put it: “In fact, the devolution train” has already “left the station in December 2004.”

It is no doubt all very complicated and difficult. Does the need for a better educated and trained work force, for instance, mean that the Inuit have to turn themselves into northern replicas of the economically disciplined southern suburbanites who haunt the environs of such places as Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver – and Ottawa itself?

It is no doubt all very complicated and difficult. Does the need for a better educated and trained work force, for instance, mean that the Inuit have to turn themselves into northern replicas of the economically disciplined southern suburbanites who haunt the environs of such places as Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver – and Ottawa itself?

Do the Inuit whose still quite recent (and more adventurous and interesting?) ancestors still spent the winter in snow houses and hunted ringed seals actually want to do this anyway? Is the current cultural struggle over such questions a big factor behind “the well-known social ills … high crime rates, widespread substance abuse, family violence,” and so forth?

Here as elsewhere, it can probably be reasonably claimed that former Liberal governments in Ottawa often enough talked a better game than they actually walked. But whether Mr. Harper’s new Conservative minority government will be able or even wants to do much better remains a very open question. The best advice right now may nonetheless be to take some heart from Premier Okalik’s view that: “I don’t necessarily agree with all the contents” of the Mayer report, “but I must say it’s a start and I look forward to good discussions with Minister Prentice.”

Meanwhile, it may be some kind of good sign too that the coming wider June 29 Aboriginal Day of Protest will probably not be as important in Nunavut as in some other parts of Canada. Premier Okalik, for one thing, will no doubt be saving most of his energy for his duties as host of the 2007 Western Premier’s Conference, July 46. As the summer heat starts to seriously set in over much of the sultry south, many Canadians will also periodically find it comforting to think that even in the middle of June CBC News has been reporting the temperature in Iqaluit at a mere 5 degrees Centigrade.

Meanwhile, it may be some kind of good sign too that the coming wider June 29 Aboriginal Day of Protest will probably not be as important in Nunavut as in some other parts of Canada. Premier Okalik, for one thing, will no doubt be saving most of his energy for his duties as host of the 2007 Western Premier’s Conference, July 46. As the summer heat starts to seriously set in over much of the sultry south, many Canadians will also periodically find it comforting to think that even in the middle of June CBC News has been reporting the temperature in Iqaluit at a mere 5 degrees Centigrade.

And whatever else again, it really is quite remarkable that Canada today includes such an experimental place as the new Nunavut Territory. Almost all Canadians in all parts of the country ought to be able to take at least some joy from that.