Iroquois origins of modern Toronto

Aug 5th, 2006 | By C. M. W. Marcel | Category: Heritage Now It used to be said that modern Toronto began in the late 18th century, when John Graves Simcoe pitched Captain Cook’s “canvas house” more or less in the middle of the present city downtown, on behalf of the British empire on which the sun never dared to set.

It used to be said that modern Toronto began in the late 18th century, when John Graves Simcoe pitched Captain Cook’s “canvas house” more or less in the middle of the present city downtown, on behalf of the British empire on which the sun never dared to set.

Nowadays many who take an interest in such things have come to see that the deepest origins of the place stretch further back into the middle of the 17th century. And the earliest founders were the same Great Lakes Iroquois who are protesting unsettled land claims in Caledonia, Ontario, some distance to the south and west, in the summer of 2006.

1. A last quick look at the old story

The old story about Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s founding moment, some students of the subject will rightly protest themselves, is still apt enough, if what you mean by “modern Toronto” is the urban streetscape of the present-day city downtown.

The old story about Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s founding moment, some students of the subject will rightly protest themselves, is still apt enough, if what you mean by “modern Toronto” is the urban streetscape of the present-day city downtown.

But if what you mean is raw human settlement, meant to exploit the surrounding resource hinterland in the interests of a rising new world economy (the original of today’s “city with the heart of a loan shark”), the Toronto where Simcoe pitched Captain Cook’s unusually large tent in the summer of 1793 was already about a century and a quarter old.

As Mrs. Simcoe noted in her still interesting diary, when the British party’s sailing ship arrived at the entrance to Toronto harbour, at the end of July 1793, “St. John Rousseau, an Indian trader who lives near, came in a boat to pilot us.” The family of Jean Baptiste Rousseau had done business in what was then called Toronto for a few decades at that juncture. Ancestors of his immediate Mississauga neighbours had been in the area for perhaps as long as a century.

Still more to the point, in the summer of 1793 Rousseau’s house and fur-trade outpost was on the east bank of what is now known as the Humber River, not too far south of an old Iroquois village and fur-trade outpost called Teiaiagon. This was established sometime in the 1660s or 1670s – along with another Iroquois village and trading outpost called Ganatsekwyagon, more or less at the Lake Ontario mouth of what is now called the Rouge River.

On any comprehensive long view, it was the Iroquois trading villages of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon, perhaps as many as 130 years before Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, that planted the very first seeds of modern Toronto – Canada’s largest metropolis today (and the sixth or seventh largest in North America). The villages themselves lasted for no more than a generation. But they set in motion a chain of events whose initial “Indian-European” culmination (or, in an earlier lexicon, “French and Indian”) was the outpost at Fort Rouillé, or Fort Toronto, in the early 1750s.

On any comprehensive long view, it was the Iroquois trading villages of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon, perhaps as many as 130 years before Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe, that planted the very first seeds of modern Toronto – Canada’s largest metropolis today (and the sixth or seventh largest in North America). The villages themselves lasted for no more than a generation. But they set in motion a chain of events whose initial “Indian-European” culmination (or, in an earlier lexicon, “French and Indian”) was the outpost at Fort Rouillé, or Fort Toronto, in the early 1750s.

This old French fort was burned to the ground by its fleeing 15-man garrison, in the face of invading British forces in the summer of 1759. Yet the resilient Toronto trading outpost of Jean Baptiste Rousseau and his Mississuaga neighbours in the early 1790s shows how the continuing economic and geographic logic of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon had survived the final mere military defeat of the old French empire in America, a generation before.

The streetscape founder “Governor Simcoe” himself (just a local variation on, e.g., Governor James Oglethorpe in Georgia, some 60 years earlier) was lured to the location by his own perceptions of this same logic. So it was, as the pioneering and still engaging early Toronto historian Percy Robinson explained in the 1930s, “from the house of Jean Baptiste Rousseau, at the foot of the Toronto Carrying-Place on the east bank of the Humber, that Simcoe and his party set out on the morning of September 25, 1793, on an exploring trip to Matchedash Bay” – due north of Toronto on the alluring sidebar to Lake Huron known nowadays as Georgian Bay.

If you really want to know how and why the modern Toronto metropolis got started, that is to say, the story of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon in the 17th century is the serious place to begin. And in a number of ways it may have more to do with the story of Toronto today, in the early 21st century, than John Graves Simcoe and Captain Cook’s canvas house.

[CW EDITORS’ NOTE: this is a very long piece, especially intended for the few who may be deeply interested in the dark past. Other readers may just want to scroll down to the last and more present-minded section 15 below.]

2. Dark prelude: Iroquois conquest of Huronia

The indispensable immediate background to the establishment of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon in the 1660s and 1670s is the shattering conquest of the northern Iroquoian-speaking peoples that the French called the Huron (or the Huron-Petun) and the Neutral, in present-day Southern Ontario, by the southern Five Nations Iroquois from what is now northern New York State – during the late 1640s and early 1650s.

The indispensable immediate background to the establishment of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon in the 1660s and 1670s is the shattering conquest of the northern Iroquoian-speaking peoples that the French called the Huron (or the Huron-Petun) and the Neutral, in present-day Southern Ontario, by the southern Five Nations Iroquois from what is now northern New York State – during the late 1640s and early 1650s.

This Iroquois conquest of the region north of the Great Lakes is the culmination of the surprisingly dramatic first chapter in the written history of the modern Canadian Province of Ontario – when adventurers and missionaries from France first met and mingled with the remarkable Huron Confederacy and its neighbours, during the first half of the 17th century.

(And the quite substantial literature that French missionaries produced about this encounter must have informed the provocative concept of the “noble savage,” later advanced by the European political theorist Jean Jacques Rousseau [17121778], who helped prepare the way for the French Revolution of 1789.)

In its broadest context, rivalry and conflict between the Huron and the Five Nations Iroquois in the Great Lakes pre-dates the arrival of Europeans. (Traditional Iroquoian warriors, who fought with wooden clubs and bows and arrows without “iron arrowheads,” even wore “a kind of armor made of thin pieces of wood laced together with cords.”)

But Huron-Iroquois warfare quickly became entangled with the wilderness struggle for mastery among rival European nations, that accompanied the formative long westward expansion of the multicultural Indian-European fur trade in northern North America (and in various more southerly parts of the continent as well)

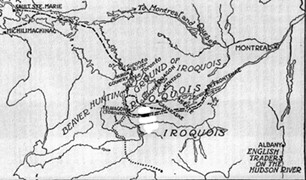

In very broad brush strokes, the Huron became allied with the French, headquartered in present-day Quebec City and Montreal, on the St. Lawrence River (which led to the Atlantic Ocean). The Five Nations Iroquois became allied with first the Dutch and then the English, headquartered in present-day Albany and New York City on the Hudson River (which also led to the sea – which led in turn to the markets of Western Europe, during the infancy of what we call “the world economy” today).

To make a long and very intriguing story very short, by the early 1650s the Five Nations Iroquois from what is now northern New York State had emerged awesomely triumphant in the first cataclysmic “Beaver War”of the early modern age in the Great Lakes. The Huron, between present-day Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay, and their so-called “Neutral” neighbours, at the western end of Lake Ontario, had been effectively driven from the region.

To make a long and very intriguing story very short, by the early 1650s the Five Nations Iroquois from what is now northern New York State had emerged awesomely triumphant in the first cataclysmic “Beaver War”of the early modern age in the Great Lakes. The Huron, between present-day Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay, and their so-called “Neutral” neighbours, at the western end of Lake Ontario, had been effectively driven from the region.

Yet during these early acts in a much longer drama aboriginal peoples were still only very vaguely attached to their new European allies. As we can appreciate nowadays, the Five Nations Iroquois had struck a first great blow for the political and economic interests of what would later become the anglophone Empire State of New York. But, for the time being, French power north of the lakes did not suffer the same dark fate as the Huron and Neutral confederacies.

Something of the economic and geographic culture of the Huron (or “Wendat,” as the people said themselves), which still lay at the bottom of this French power in the region, also still survives today.

As explained in the 1930s, by the eminent fur-trade historian Harold Innis – first Canadian-born Chairman of the Department of Political Economy at the University of Toronto (and an inspiration for the 1960s career of the communications guru Marshall McLuhan): “The struggle waged between the Iroquois and the Huron was a prelude to the struggle between New York and Montreal, which dominated the economic history of Ontario.”

3. Empty north shore and the Iroquois war with the Susquehannocks

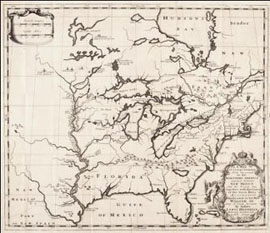

Even during the early 17th century, the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario, where modern Toronto now stands, was an unoccupied native hunting ground. Present-day archaeology, however, has shown that, perhaps as late as the 16th century, it had been a place of recurrent human habitation, stretching back for millennia.

Even during the early 17th century, the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario, where modern Toronto now stands, was an unoccupied native hunting ground. Present-day archaeology, however, has shown that, perhaps as late as the 16th century, it had been a place of recurrent human habitation, stretching back for millennia.

It would even seem that something of what became the more northerly Huron Confederacy, discovered by the French in the early 1600s between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay, had originally been located in today’s Toronto region. Perhaps during earlier phases of “struggle waged between the Iroquois and the Huron,” some among the later Huron had moved from the southern to the northern end of the long inland canoe portage or “Toronto Passage” between Lake Ontario and Georgian Bay (or the lower and upper Great Lakes).

In any case, once the Iroquois had emerged triumphant in the first cataclysmic Beaver War north of the lakes, in the early 1650s, the strategic economic and geographic logic of the north shore of Lake Ontario reasserted itself – with a helping hand from continuing (and often quite bloody) Iroquois military adventures, further south.

Even today this story remains shrouded in the romantic mists of what early Europeans saw as the “primeval lakes and forests” of northeastern North America. Yet it is clear enough that, from the Gulf of the St. Lawrence all the way south to the James River in Virginia, the arrival of the Dutch, English, French, and Swedish close to the Atlantic coast in the earlier 17th century helped stimulate and shape conflicts among native North Americans further inland.

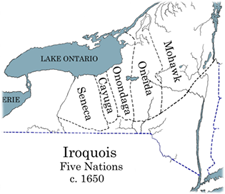

In the early 1660s, northern New York’s increasingly warring and ambitious Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy – of the (from east to west) Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – was also involved in a struggle with still other, more southerly Iroquoian-speaking peoples, focused around the Susquehanna River in the present-day Mid-Atlantic States, and known as the Susquehannocks (and also called the Andastes in some French sources still extant).

In the early 1660s, northern New York’s increasingly warring and ambitious Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy – of the (from east to west) Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca – was also involved in a struggle with still other, more southerly Iroquoian-speaking peoples, focused around the Susquehanna River in the present-day Mid-Atlantic States, and known as the Susquehannocks (and also called the Andastes in some French sources still extant).

It is clear enough as well that, for whatever exact deeper reasons, the Five Nations Iroquois had developed their own unusually strong and cunning awareness of the opportunities for vast new wealth and power that the early global economy had brought to the North American interior. By the middle of the 17th century, the descendants of Hiawatha (near legendary political founder of the Five Nations Confederacy, in, say, 1570, or the 1550s, or as early as 1390?) had formed a fierce resolve to make the most of the new opportunities – as such things were then understood in the romantic but also sometimes sinister and violent lakes and forests.

(The Iroquois had never read Machiavelli, founder of modern European political thought in the political jungle of Renaissance Italy, during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. But they somehow acquired their own understanding of his central message all the same.)

4. Iroquois villages on the north shore, 1660s1680s

Like others, the meticulous late 20th century archaeological and anthropological historian of the 17th century Great Lakes, Bruce Trigger, has also drawn attention to the (still quite crude and uncertain) European firearms of the era.

Like others, the meticulous late 20th century archaeological and anthropological historian of the 17th century Great Lakes, Bruce Trigger, has also drawn attention to the (still quite crude and uncertain) European firearms of the era.

The Five Nations Iroquois were apparently readily able to obtain this most advanced military technology of the day from the Dutch and then the English at New York. But this was only an advantage – insofar as it was – against the northern native allies of the less forthcoming French (and especially the Neutral who altogether “lacked guns”).

In the south things were different. As Professor Trigger similarly explained in the 1970s: “Aid sent from the English colony of Maryland [and New York was still Dutch at this point] permitted the Susquehannocks to withstand a major Iroquois attack in 1663. [Among other things, the Susquehannock villages were defended by European cannon.’] As the war continued, many Cayugas fled from their tribal territory and settled along the north shore of Lake Ontario.”

Some Oneidas and Senecas subsequently joined this northward movement – and for economic and geographic as well as strictly military and security reasons. Percy Robinson set out a still serviceable earlier 20th century account of the resulting new Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario, as long ago as the 1930s.

By the late 1660s, Robinson urged, various Five Nations Iroquois “had established themselves where the trails led off into the interior, to the richer hunting grounds of the north. Beginning at the eastern end of Lake Ontario, the names of these Iroquois villages are …

“Ganneious on the site of the present … town of Napanee, a village of the Oneidas [also, to be very up to date, the 1980s birthplace of today’s teen-throb pop-singer Avril Lavigne, who was recently married in southern California];

“Kente on the Bay of Quinte, Kentsio on Rice Like, Ganaraske on the site of the present town of Port Hope, villages of the Cayugas who had fled from the menace of the Andastes to a securer position beyond the lake;

“Ganatsekwyagon at the mouth of the Rouge and Teiaiagon at the mouth of the Humber, villages of the Senecas who had established themselves at the foot of the two branches of the Toronto Carrying-Place and were thus in command of the traffic across the peninsula to Lake Simcoe and the Georgian Bay.”

(And finally, for who knows exactly what deeper reasons again, Percy Robinson’s list leaves out a last if apparently small Seneca village that almost certainly ought to be included, even from his unique early 20th century Torontonian’s point of view. This was Quinaouatoua or Tinawatawa, on the portage or carrying-place from the western end of Lake Ontario to the Grand River, and thence to Lake Erie – more or less in the present-day city of Hamilton: and the former earlier 17th century homeland of the Neutral confederacy.)

5. North by northwest: the strategic economic geography of the Toronto Passage

Even the more easterly Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario, which seem to have started as refuges from the conflicts of the 1660s with the more southerly Susquehannocks, also had a strategic geographic and economic logic, tied to the advancing Indian-European fur trade.

Even the more easterly Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario, which seem to have started as refuges from the conflicts of the 1660s with the more southerly Susquehannocks, also had a strategic geographic and economic logic, tied to the advancing Indian-European fur trade.

The Kawartha Lakes waterway, stretching in a leisurely arc from Georgian Bay on Lake Huron to the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario, was at least one (rather long) shortcut between the so-called upper and lower Great Lakes.

More exactly, from points along the north shore beneath the Kawartha Lakes, so to speak, Iroquois middlemen could lure fur pelts from the Algonkian-speaking peoples of the far northern and northwestern interior towards the Dutch and then the English at Albany and New York. In the absence of such arrangements these same pelts would most likely go down the more northerly and easterly Ottawa River, to the French at Quebec City and Montreal.

Yet as Percy Robinson’s account implies, the Kawartha Lakes passage from the lower to the upper lakes was a minority option for northern Algonkian hunters who preferred the scenic aboriginal canoe route south. The wilderness commercial magnetism of the shorter and more direct inland portage or “Toronto Passage” (or Carrying-Place), running more or less due north from the nicely harboured northwestern shore of Lake Ontario to Georgian Bay, was much stronger than the leisurely attractions of the more easterly Kawartha Lakes.

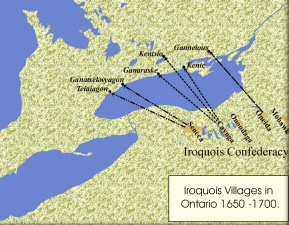

As Percy Robinson notes as well, there were two branches to the more southerly reaches of this Toronto Passage. Ganatsekwyagon, near the Lake Ontario mouth of today’s Rouge River, was the Seneca village on the easterly branch of the passage. Teiaiagon, near the mouth of the Humber, was on the westerly branch.

There are suggestions in the sources readily at hand today that Ganatsekwyagon may have been established earlier than Teiaiagon. More or less at the mouth of the Rouge and far enough east of the interfering Toronto Islands (or peninsula as it was then, and would be until a great storm in the middle of the 19th century), Ganatsekwyagon was arguably the more immediately obvious strategic location at the foot of the Toronto Passage to the north (and northwest). And it is clear from surviving written records that it had been established by the late 1660s.

Robinson’s still engaging if almost too richly detailed pioneer study of the 1930s appears to assume that Teiaiagon had also been established by the late 1660s. But in an early 1980s article the historical geographer Victor Konrad stressed that this is only an assumption. As yet no written records have been discovered that actually mention Teiaiagon in the 1660s.

Konrad seems to suggest as well that Teiaiagon may have effectively replaced or gradually succeeded Ganatsekwyagon as the Seneca’s main Toronto Passage village, in the 1670s. Soon enough, on this hypothesis, it became clear to those involved that the westerly branch of the Passage’s southern end on the Humber River was the more profitable route.

If this is true, it had to do with subsequent subtler appreciations of the shoreline geography – and with developments among both the native Seneca from northern New York and the French newcomers on the St. Lawrence River (who, unlike the conquered Huron and Neutral confederacies, continued to assert an increasingly strong grip on the Great Lakes interior, as the 17th century wore on).

6. Algonkian hunters, Iroquoian middlemen, and the English conquest of the Dutch

Some have always found it hard to accept that the North American Great Lakes region was thrown into such vast turmoil in the 17th century All for a Beaver Hat, in such places as Amsterdam, London, and Paris. That is nonetheless the message that the early modern regional history ultimately conveys.

Some have always found it hard to accept that the North American Great Lakes region was thrown into such vast turmoil in the 17th century All for a Beaver Hat, in such places as Amsterdam, London, and Paris. That is nonetheless the message that the early modern regional history ultimately conveys.

The crucial point of the final Huron-Iroquois conflict of the late 1640s and early 1650s, however, had not exactly been who would get to hunt for the furs that formed the essential raw materials of an increasingly fashionable gentlemen’s beaver-hat industry in Western Europe. The best hunters of the best furs for European hats were the more northerly Algonkian-speaking peoples.

The Iroquoian-speaking peoples of the Huron and the Iroquois were more technologically developed farmers and traders – and warriors. Such Algonkian-speaking peoples as the Algonquin, Chippewa, Cree, Mississauga, Ojibwa, and Ottawa were still primarily “hunters and gatherers” (though, especially among the Algonquin, also manufacturers of prized and commercially very crucial elegant birch-bark canoes).

What the Huron and Iroquois finally fought over was who would be the more ambitious aboriginal middlemen, profitably mediating the relationship between the Algonkian-speaking hunters of the interior and the European merchants, closer to the Atlantic coast.

In the early 1650s part of the vanquished Huron Confederacy had fled to what is now the village of Lorette, near Quebec City. But in some respects, the ultimate effective strategists among the French seem to have been not too unhappy about the shattering Iroquois conquest of their Huron allies. The French increasingly preferred to deal directly with the Algonkian-speaking hunters themselves, without aboriginal middlemen.

(On one ancient theory that seems to have been debated for a few centuries now, without any quite convincing conclusion, the predominantly Catholic Christian and less economically individualist French just got on better with “the Indians” than the predominantly Protestant and more individualist Dutch and English. And so they did not need aboriginal middlemen to the same degree, in their Indian-European business dealings.)

Yet by the middle of the 17th century the Iroquois conquest of Huronia had at least put the Five Nations Confederacy in command north of the Great Lakes for the time being. The rise of the Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario during the 1660s confirmed the point.

To add to this plot, Peter Stuyvesant’s surrender of the old Dutch New Amsterdam (New York) and Fort Orange (Albany) to the English, on August 16, 1664, also began to alter the wilderness balance of Indian-European power in the Great Lakes, to the ultimate Iroquois advantage.

(And as the eminent old English historian Sir George Clark has explained, in one of his books of the 1930s, Stuyvesant’s surrender of the early Dutch North American enterprise “closed the gap in the English possessions along the American coast-line and gave us the command of the trade-route from the Great Lakes through the Hudson-Mohawk gap to a seaport appointed by geography to become one of the world’s great cities … now called New York.”)

7. French-Iroquois Treaty of 1667

The Five Nations Confederacy would not remain in command on the north shore of Lake Ontario forever (or even all that long).

The Five Nations Confederacy would not remain in command on the north shore of Lake Ontario forever (or even all that long).

In the later 1660s the French began taking their own aggressive actions to restrain, among other things, the flow of furs from the north-shore Iroquois trading villages to the new English (and surviving old Dutch) traders and merchants at Albany and New York – as opposed to the French themselves at Quebec City and Montreal.

The first French step in what quickly enough unfolded as a quite systematic strategy was to strike a blow against the Five Nations’ military might (already weakened by the ongoing struggle with the Susquehannocks to the south, at the edge of the rising English Mid-Atlantic colonies). In 1665 French imperial officials sent a military force known as the Carignan-Salieres regiment off into the wilderness of “Canada or New France.”

Then, as the historical geographer Victor Konrad has explained: “In the spring of 1666, the Viceroy and the Governor of Canada, with 28 companies of foot and all the militia of the colony, marched into the country of the Mohawks” [the most easterly of the Five Nations Iroquois].

The vaunted military might of the French Sun King Louis XIV had some trouble adjusting to the rugged lakes and forest of northeastern North America. As the leaves returned to the trees in the spring of 1666, Konrad goes on: “The Mohawks retired into the woods and all the French were able to do was burn some villages and murder some old Sachems.”

Yet, in the parallel report of Bruce Trigger, this was enough to secure a French-Iroquois “treaty embracing the whole confederacy” in 1667, “after the Carignan-Salieres Regiment had burned the Mohawk villages and food supply.” (Though the exact status of the especially fierce Mohawks themselves remained somewhat ambiguous in the written version of the treaty that survives in the National Archives of Canada, “for the present time.”)

Whatever else, the French had made it very clear that (unlike the Huron and the Neutral) they would not be dispersing from the region north of the Great Lakes, in any then foreseeable future.

8. The French at Ganatsekwyagon, Fort Frontenac, and the rise of Teiaiagon

Even under the French-Iroquois treaty of 1667, the new Iroquois villages remained on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The Iroquois would still be in command there for a while yet. The next step in the ongoing French plot, however, was to send Christian missionaries to the villages, to aid the resident heathen in their spiritual lives (as the Huron had been aided in the darker past).

Even under the French-Iroquois treaty of 1667, the new Iroquois villages remained on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The Iroquois would still be in command there for a while yet. The next step in the ongoing French plot, however, was to send Christian missionaries to the villages, to aid the resident heathen in their spiritual lives (as the Huron had been aided in the darker past).

Dollier de Casson of the Sulpician order has left us an account of these beginnings: “It was in the year 1668 that we were given the task of setting out for the Iroquois, and Quint [Kent in Percy Robinson’s lexicon] was assigned to us as the centre of our mission because in that same year a number of people from that village had come to Montreal and had definitely requested us to go and teach them in their country …”

The next year – as Percy Robinson put it in the 1930s – the Sulpician “M. de Fnelon, the fiery half-brother of the famous Archbishop of Cambrai … in company with another missionary, M. d’Urf, passed the winter of 1669 and 1670 in the village of Ganatsekwyagon, a fact which is commemorated by the name Frenchman’s Bay, which clings to the inlet near the mouth of the Rouge. This is the first recorded residence of white men in the neighbourhood of Toronto.”

(In the early 21st century we would more aptly just say non-aboriginal people: “white men” being a mere minority in Toronto today – though they were almost certainly at least somewhat less than a democratic majority in Robinson’s day too.)

In 1669 as well (on Robinson’s account again) “possibly before the arrival of Fnelon and d’Urfe in the village of Ganatsekwyagon … two notable explorers, Pere and Joliet, camped for a time at that village before crossing le passage de Toronto to the Georgian Bay. They were on their way to Lake Superior in search of the great copper mine reported to exist in that region. It has been thought that this was not the first visit of Pere to the locality, and that he visited the site of the city of Toronto in the preceding year; he was the first French trader on Lake Ontario.”

Only a few years later, the French plot north of the lakes started to grow still thicker. In 1673 the local agents of Louis XIV established their own military outpost at Cataraqui, where Lake Ontario meets the St. Lawrence River (on the site of the present-day city of Kingston). It was called Fort Frontenac – after perhaps the most able and ambitious of all French governors of Canada or New France, the Comte de Frontenac (16721682, and then again 16891698).

Only a few years later, the French plot north of the lakes started to grow still thicker. In 1673 the local agents of Louis XIV established their own military outpost at Cataraqui, where Lake Ontario meets the St. Lawrence River (on the site of the present-day city of Kingston). It was called Fort Frontenac – after perhaps the most able and ambitious of all French governors of Canada or New France, the Comte de Frontenac (16721682, and then again 16891698).

The construction of Fort Frontenac actually “began during negotiations between Governor Frontenac and a delegation of Iroquois [from the various north shore villages] in July 1673.” Both the earlier and later 20th century students of early modern Toronto, Percy Robinson and Victor Konrad, urge that Fort Frontenac was intended to rival or even replace Ganatsekwyagon further west, and serve as a fur-trade outpost channelling beaver pelts northeast to Montreal and Quebec City, instead of southeast to Albany and New York.

In the fall of 1674 Frontenac himself wrote to Louis XIV in France that the Iroquois “have given their word not to continue the trade, which as I informed you last year, they had commenced to establish at Ganatsekwyagon, with the Ottawas, which would have absolutely ruined ours by the transfer of the furs to the Dutch.”

To complicate matters, the Dutch had recaptured New York from the English in the summer of 1673. But it was returned to the English for good in a treaty of November 1674.

Robinson has speculated that subsequently “the English and the Iroquois, foiled by Fort Frontenac in their trade at Ganatsekwyagon, which they had reached along the north shore of Lake Ontario, now began to trade at Teiaiagon, which they reached by following the south shore round the western end of the lake.”

Unlike Ganatsekwyagon, Teiaiagon had not been represented at the summer 1673 Iroquois negotiations with Count Frontenac, during which the construction of Fort Frontenac was pointedly begun (and ultimately matched with a companion Oneida village).

Konrad seems to suggest that Teiaiagon itself may only have been established in response to Fort Frontenac, and, conceivably, to the Iroquois promise that they would not trade with the English and the Dutch at Ganatsekwyagon. One way or another, the construction of Fort Frontenac seems to have increased the relative importance of Teiaiagon.

9. King Phillip’s War, Bacon’s Rebellion, and La Salle at Teiaiagon

Any notion that Teiaiagon would become an exclusive resort of English and Dutch traders was refuted by the prompt enough appearance there of the legendary French adventurer who explored the “Great West” of the Mississippi Valley, and claimed the vast continental heartland of Old Louisiana for the King of France, Ren Robert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle. (And this was not the present modest state of Louisiana – but the much larger region of the Mississippi basin, that Thomas Jefferson would finally purchase from Napoleon in 1803, for 60 million French francs.)

Any notion that Teiaiagon would become an exclusive resort of English and Dutch traders was refuted by the prompt enough appearance there of the legendary French adventurer who explored the “Great West” of the Mississippi Valley, and claimed the vast continental heartland of Old Louisiana for the King of France, Ren Robert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle. (And this was not the present modest state of Louisiana – but the much larger region of the Mississippi basin, that Thomas Jefferson would finally purchase from Napoleon in 1803, for 60 million French francs.)

By 1675 the Comte de Frontenac had granted the land surrounding Fort Frontenac to La Salle. And in the course of his subsequent adventures Ren Robert Cavalier would (in Percy Robinson’s words) cross “the Toronto Carrying-Place … from Teiaiagon … on three and possibly four occasions.”

Meanwhile, two great if still often under-appreciated conflicts on the more southerly Atlantic coast, in 1675-1676, cast some big ripples on the north shore of Lake Ontario as well.

King Phillip’s War in New England was the first appallingly bloody full-scale conflict between the new Anglo-American settlement frontier and the aboriginal peoples of North America. Still further south, the coterminous Bacon’s Rebellion was a more untidy frontier rebellion against a new planter or “tidewater aristocracy” (with its own early fur-trade connections), mixed in with Indian-European conflict.

One immediate consequence, as Bruce Trigger has explained, was that the “final breaking of the power of the Susquehannocks in 1675 did not come about as the result of an Iroquois victory, but because of an attack by European backwoodsmen from Maryland and Virginia.” This nevertheless relieved the earlier pressure from the south on the Great Lakes Iroquois.

One immediate consequence, as Bruce Trigger has explained, was that the “final breaking of the power of the Susquehannocks in 1675 did not come about as the result of an Iroquois victory, but because of an attack by European backwoodsmen from Maryland and Virginia.” This nevertheless relieved the earlier pressure from the south on the Great Lakes Iroquois.

With the Susquehannocks broken, the strictly military and security logic behind the Cayuga north shore villages, east of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon, also began to fade.

Meanwhile again, as recounted by Percy Robinson, “La Salle crossed the Toronto Carrying-Place in 1680 from Teiaiagon to Michilimackinac [where Lake Huron and Lake Michigan meet], and in 1681 from Michilimackinac to Teiaiagon on his way to Fort Frontenac, and again in the same year on his way back to Michilimackinac.”

In the magisterial text of the earlier 20th century New England historian Samuel Eliot Morison, La Salle’s “greatest adventure” began in “the last month of 1681,” when with “23 Frenchmen and 31 Indians, mostly refugees from King Phillip’s War, he struck out … for the Mississippi.”

10. Teiaiagon at its height

The Teiaiagon that figured in La Salle’s adventures would seem to have been a typical enough Great Lakes Iroquoian village of its era.

The Teiaiagon that figured in La Salle’s adventures would seem to have been a typical enough Great Lakes Iroquoian village of its era.

There is a consensus nowadays that it was located on a modest hill on the east bank of the Humber River, not too far north of the river’s Lake Ontario mouth. (The site is now known as Bby Point [pronounced Baa-bee, or as some local anglophone residents today say, “Bobby”]. The name commemorates a notable French Canadian family from the Windsor-Detroit area, represented on Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s Legislative Council. They would be granted the land in the late 18th century – in preference to the more deserving Jean Baptiste Rousseau, whose family may have been too “French and Indian” for the new British imperial officialdom.)

On a reasonable guess in the early 21st century, the village of Teiaiagon was home to at least a few hundred and possibly considerably more Seneca in the late 1670s and early 1680s. They lived in a number of longhouses, and Percy Robinson urges: “We may be sure that Teiaiagon was protected by a stout palisade and fortified with all the skill which the Iroquois could command.”

Outside the palisade were cornfields, tended by the women of the village (on forest land cleared by the men) – and providing the great bulk of the local food supply, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Outside the palisade were cornfields, tended by the women of the village (on forest land cleared by the men) – and providing the great bulk of the local food supply, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering.

The written sources still extant offer a few intriguing snapshots of life at Teiaiagon at its height. According to Robinson in the 1930s again, sometime in the 1670s “a party of La Salle’s men from Cataraqui were at Teiaiagon and engaged in a drunken debauch a rather melancholy beginning for Toronto the good!”

Robinson goes on to quote his French source directly: “The Carnival of the year 167 six traders from Kataraak8y named Duplessis, Ptolme, Dautru, Lamouche, Colin and Cascaret made the whole village of Taheyagon drunk, all the inhabitants were dead drunk for three days; the old men, the women and the children got drunk.”

Robinson notes as well: “The same document mentions the fact that two women were stabbed at Tcheiagon (Teiaiagon) in 1676 as the result of a drunken brawl, possibly the same occasion.”

We also know that a French ship of about 10 tons sought refuge from a Lake Ontario storm at the mouth of the Humber River, on November 26, 1678.

One of those on board was Father Hennepin, a Rcollet missionary from Fort Frontenac, and he has left an account: “We came pretty near to one of … the Iroquoese … Villages call’d Tejajagon … We barter’d some Indian corn with the Iroquoese, who could not sufficiently admire us, and came frequently to see us on board our Brigantine … The wind turning then contrary, we were oblig’d to tarry there til the 15th of December, 1678, when we sail’d from the Northern Coast to the Southern, where the River Niagara runs into the Lake.”

One of those on board was Father Hennepin, a Rcollet missionary from Fort Frontenac, and he has left an account: “We came pretty near to one of … the Iroquoese … Villages call’d Tejajagon … We barter’d some Indian corn with the Iroquoese, who could not sufficiently admire us, and came frequently to see us on board our Brigantine … The wind turning then contrary, we were oblig’d to tarry there til the 15th of December, 1678, when we sail’d from the Northern Coast to the Southern, where the River Niagara runs into the Lake.”

Percy Robinson tells us too that La Salle himself actually wrote a letter dated at Teiaiagon, during one of his visits in the early 1680s. On just which of his visits the letter was written appears somewhat unclear in Robinson’s text. But the still-towering New England historian of the 19th century, Francis Parkman, has also written about La Salle’s second visit of 1681:

“At the beginning of autumn, he was at Toronto, where the long and difficult portage to Lake Simcoe detained him a fortnight. He spent part of it in writing an account of what had lately occurred to a correspondent in France, and he closes his letter thus: “This is all I can tell you this year. I have a hundred things to write, but you could not believe how hard it is to do it among Indians. The canoes and their lading must be got over the portage, and I must speak to them continually, and bear all their importunity, or else they will do nothing I want. ”

11. A gathering storm

In the earlier 1680s all the Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario began to acquire increasingly short leases on life – as both the French and Iroquois plots in the Great Lakes region thickened again.

In the earlier 1680s all the Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario began to acquire increasingly short leases on life – as both the French and Iroquois plots in the Great Lakes region thickened again.

To start with, the breaking of the Susquehannocks to the south in 1675, during Bacon’s Rebellion, had freed the imagination of Hiawatha’s most Machiavellian descendants among the the Five Nations Confederacy. And as Bruce Trigger has reported, “the Iroquois were driven to launch a full-scale war against the Illinois in 1680.”

The Illinois commanded the vast fur-trade hinterland south of the most westerly Great Lakes (as the name of the current state of the union whose great metropolis is Chicago still suggests). In a second (or third?) cataclysmic Beaver War of the Great Lakes region, the fierce Five Nations Iroquois from northern New York would clear this new mid-western hinterland too.

Yet La Salle and others had already begun to open up the same area for the French. On Trigger’s account, the French-Iroquois “peace of 1667” itself “made it easier for the French not only to trade in the north but also to extend their trade routes through the lower Great Lakes into the Illinois country.” When they attacked the Illinois, the Iroquois were not in “conflict merely with Indian traders but with Frenchmen who were competing with them for furs.”

The French by this point were also firming up their own more direct and intimate alliances with the aboriginal hunters of the interior. In the same 1667 French-Iroquois treaty it had already been declared that “the Huron or Algonkians” were “subjects of the said Lord King,” Louis XIV, “or living under His protection.” And the French subsequently strengthened their practical relationships with the more northerly Algonkian-speaking peoples of present-day Ontario – who were learning more about the old country of the Huron and the Neutral, from the Iroquois traders at Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon themselves.

Something of the dark fate that all this background foretold for all the Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario is hinted at in Percy Robinson’s report (from a French source) that in 1682 “the Iroquois” were “plundering three Frenchmen” at Teiaiagon, named Abraham, Lachapelle, and Leduc.

(Remarkably enough, an early 21st lady named Adrienne Leduc has a website called Letter to La Salle, where she writes: “I cast my thoughts back to Teiaiagon, now Baby Point, Toronto … There, in the summer of 1682, the Senecas plundered the canoes of three Frenchmen – Lachapelle, Leduc, and Abraham. The three traders lost their cargoes but luckily kept their scalps. One of these men was my husbands’s ancestor.”)

Despite the plundering, the Seneca at Teiaiagon (and Quinaouatoua at the western end of Lake Ontario, somewhere around the present city of Hamilton) seem to have been more friendly towards the French than their four more easterly fellow nations of the Iroquois confederacy – an inclination that would have a few subsequent echoes over the next three generations. Another larger destiny, however, was blowing in the wind.

In Bruce Trigger’s words: “Having dispersed the Indian nations that had surrounded them, the Iroquois were now forced to enter an era of more direct involvement with the European powers that were establishing themselves in North America.” For the most part, the Five Nations Iroquois would finally be fierce allies and wilderness agents of the English at Albany and New York, not the French at Quebec City and Montreal. And a vast new conflict between the French and the Iroquois was brewing – in both the northern and the western Great Lakes.

12. Dark fate of the Iroquois villages on the north shore

Things started badly for the French, when in 1682 Count Frontenac was replaced as Governor of Canada or New France by the less able and ambitious Sieur de la Barre (16821685).

Things started badly for the French, when in 1682 Count Frontenac was replaced as Governor of Canada or New France by the less able and ambitious Sieur de la Barre (16821685).

In 1684, as the later 20th century historian of France in America, W.J. Eccles, has explained, La Barre set off from Montreal to avenge an Iroquois attack on a French outpost in the Illinois country, “at the head of a force of 800 men, accompanied by 378 allied Indians.”

Alas, this first French “campaign was a complete fiasco.” La Barre’s “supply system was inadequate, and Spanish influenza, brought with the troop ships, spread through the ranks of his motley army. By the time he reached Fort Frontenac at the eastern end of Lake Ontario he commanded a force that could barely stand, let alone engage the Iroquois.”

When Louis XIV heard the subsequent shameful details the next year, “La Barre was recalled in disgrace.” He was replaced by the Marquis de Denonville (1685-1689) – “brigadier of the Dragoons, a veteran soldier regarded as one of the better officers of the kingdom.” And Denonville was finally provided with an additional 1,600 “Troupes de la Marine” from France.

In 1687 (Eccles continues) “Denonville launched a well-organized campaign against the Senecas,” in their northwestern New York homeland.

In 1687 (Eccles continues) “Denonville launched a well-organized campaign against the Senecas,” in their northwestern New York homeland.

Like the Mohawks who had faced the Carignan-Salieres regiment some 20 years before, most of the Seneca just adroitly retired into the woods. But Denonville destroyed their villages “and food supplies and inflicted some casualties,” even though he “failed to make them stand and fight.” In the end, “the demonstration that the French could march an army, more than 2,000 strong counting the Indian auxiliaries, into the country of the most distant and powerful [or at least most populous] of the Iroquois nations was not without effect.”

Whether Denonville also destroyed whatever was left of the Seneca and other Iroquois villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario in his campaign of 1687 has remained a murky point down to the present.

It is clear enough that he followed the north shore of Lake Ontario back to Fort Frontenac, after his assault on the Seneca homeland in northwestern New York – and that he paused at the mouth of the Humber and then stopped at Ganatsekwyagon. What the historical geographer Victor Konrad calls “Indian allies of the French” were apparently already “in control” at Ganatsekwyagon at this point. And Percy Robinson, among others, has wondered in print “whether the governor employed the morning spent at the mouth of the Humber raiding and destroying the Seneca village of Teiaiagon.”

There are also a few strong hints in the sources readily at hand today that Denonville’s aggressive campaign of 1687 prompted the Five Nations Confederacy to recall all its pioneering people in the villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario back to the more southerly homeland in northern new York. (The original logic of the Cayuga refugee villages to the east of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon had in any case begun to fade as early as the late 1670s, once the power of the more southerly Susquehannocks had been broken in Bacon’s Rebellion. )

What both the earlier and later 20th century historians of early modern Toronto agree on is that by the end of the 1680s the Iroquois had, for whatever exact reasons, abandoned their villages on the north shore of Lake Ontario. So Percy Robinson tells us that “no mention” of Teiaiagon “has been found in any document later than 1688.” And Victor Konrad has similarly reported that: “By 1688 the Iroquois were restricted to south of the Lake.”

13. French and Mississauga Toronto

In fact, Denonville’s adventures of 1687 only precipitated a new era of fierce and bloody French-Iroquois warfare that would not abate until the early 18th century.

In fact, Denonville’s adventures of 1687 only precipitated a new era of fierce and bloody French-Iroquois warfare that would not abate until the early 18th century.

More exactly, the late 17th century marked the first extended conflict between the French and their Algonkian and other aboriginal allies on the one side, and the Iroquois and their English allies on the other. And if the Indian-European alliances were somewhat tighter at this point than they had been a half-century before, it still seems not altogether clear for us today just who was leading whom, where and when.

What is clear enough is that, at some point between the late 1680s and about 1700 (a new French-Iroquois treaty of 1701 is an often-used convenient closing date), more northerly Algonkian-speaking peoples, ostensibly allied chiefly with the French, moved onto the north shore of Lake Ontario.

(It might even be said, somewhat figuratively, that they took over the Iroquois villages of the early 1660s to late 1680s. As the historical geographer Conrad Heidenreich has urged, the “Iroquois abandoned their villages on the north shore, but these villages did not disappear.” They continued to be marked, e.g., on published European maps until the middle of the 18th century. Map publishers in Europe were not quite aware that “Algonquian-speaking Indians from the north” now occupied the north shore sites. And “since the same locations were occupied,” the “original [Iroquois] village names remained on the maps.”)

What is still debated among local historians today is just how Algonkian peoples arrived on the north shore of Lake Ontario during the late 17th century. On some accounts – based on aboriginal oral traditions whose exact interpretation remains in dispute – The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario “conquered” the area from the Iroquois, with perhaps occasional guns and ammunition from the French on the St. Lawrence River. Other readings of the story suggest a more peaceful migration, to a north shore that had already been effectively vacated by Denonville’s exploits of 1687.

What is also clear enough, however, is that, in whatever way they may or may not have arrived, a branch of the wider Ojibwa first nation known as the Mississauga had moved in to what was left of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon by the early 18th century. Drawing on published volumes in the New York Colonial Documents series, Percy Robinson and others have urged that these new Mississauga settlements were at least at first themselves vaguely allied with the Iroquois on the south shore of the lake – and through them with the English at Albany and New York.

What is also clear enough, however, is that, in whatever way they may or may not have arrived, a branch of the wider Ojibwa first nation known as the Mississauga had moved in to what was left of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon by the early 18th century. Drawing on published volumes in the New York Colonial Documents series, Percy Robinson and others have urged that these new Mississauga settlements were at least at first themselves vaguely allied with the Iroquois on the south shore of the lake – and through them with the English at Albany and New York.

Yet if this is true, it did not stop the French from strengthening their position at Toronto as the 18th century wore on – first with a so-called “Magasin Royal” (or king’s store) in the 1720s, and then with Fort Rouill, or Fort Toronto, in the 1750s. By the time of the final struggle between France and England in North America, during the world-wide Seven Years War (17561763), the Toronto-region Mississauga were more or less on the side of the French (and more or less on the side of the English were the Iroquois in northern New York).

14. The United Kingdom and the United States in North America

After Great Britain finally succeeded France as the European imperial power north of the Great Lakes, at the end of the Seven Years War (still frequently known in the USA today as the “Old French and Indian War”), English fur traders from Albany and New York were active among the Toronto Mississauga. In the early 1770s Ferrall Wade was one such trader whose career has survived in records still extant. Jean Baptiste Rousseau’s father, however, was in the area at about the same time, on behalf of the merchants in Montreal and Quebec City.

After Great Britain finally succeeded France as the European imperial power north of the Great Lakes, at the end of the Seven Years War (still frequently known in the USA today as the “Old French and Indian War”), English fur traders from Albany and New York were active among the Toronto Mississauga. In the early 1770s Ferrall Wade was one such trader whose career has survived in records still extant. Jean Baptiste Rousseau’s father, however, was in the area at about the same time, on behalf of the merchants in Montreal and Quebec City.

Then, after the American War of Independence (17761783), what remained of the British empire in America ironically took over the old role of the French empire in the true north, strong and free. For its own good reasons, Canada or New France remained loyal to the once-rival anglophone European empire it had only so recently joined. It did not become part of the new independent United States of America (despite a special provision for its eventual admission, in article 11 of the original US Articles of Confederation).

“History has many cunning passages” (according to the 20th century Anglo-American poet T.S. Eliot, who was born in St. Louis, Missouri and died in London, England). After the birth of the new American Republic, the British empire found itself defending the old French (and Indian) economic and geographic interests of Montreal and Quebec City, north of the Great Lakes. And it was John Baptiste Rousseau, born in and first married to a girl from Montreal – and not Ferrall Wade or any other trader from Albany or New York – who went out to meet Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s ship in Toronto harbour, at the end of July 1793.

Just to keep everything still more ironically diverse (if also somewhat further confused), the end of the War of Independence or “American Revolution,” in 1783, finally brought some Iroquois from northern New York back to the region north of the lakes, that they had in one way or another abandoned about a century before.

During the great military conflict that gave birth to the new Democracy in America some among what had by this point become the Six Nations Iroquois in northern New York (with the earlier 18th century addition of the Tuscarora from North Carolina) had remained loyal to the British empire as well – for their own good reasons.

During the great military conflict that gave birth to the new Democracy in America some among what had by this point become the Six Nations Iroquois in northern New York (with the earlier 18th century addition of the Tuscarora from North Carolina) had remained loyal to the British empire as well – for their own good reasons.

When the war ended, the British Crown purchased land from the Mississauga north of the lakes for these loyal Iroquois – in the Grand River valley north of Lake Erie, and by the Bay of Quinte on Lake Ontario. They became among the first northward-moving United Empire Loyalists in a new British North American Province of Upper Canada (the immediate legal and institutional precursor of the “free and democratic” Canadian Province of Ontario today – as most recently incarnated in the independent modern Canada’s Constitution Act 1982).

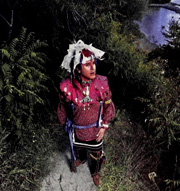

These loyal Iroquois migrants from northern New York and their descendants would help defend Canada (and the British empire) again in the War of 1812, and, much later, in the First and Second World Wars of the 20th century. And it is the same present-day Grand River Iroquois who are rather fiercely locked into a troubling land-claim protest, in Caledonia, Ontario, in the summer of 2006.

15. Survivals of Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon (and the old Toronto Passage) in the city region today

Though there can be no doubt that the Seneca village of Ganatsekwyagon was located somewhere near the mouth of the Rouge River in the 1660s, 1670s, and 1680s, exactly where has remained something of a mystery down to the present. But there has been considerable speculation on the subject in the early 21st century, among local ecological and environmental activists concerned to preserve the natural heritage of the Rouge River valley.

Though there can be no doubt that the Seneca village of Ganatsekwyagon was located somewhere near the mouth of the Rouge River in the 1660s, 1670s, and 1680s, exactly where has remained something of a mystery down to the present. But there has been considerable speculation on the subject in the early 21st century, among local ecological and environmental activists concerned to preserve the natural heritage of the Rouge River valley.

Something of the aboriginal canoe culture of 17th century Ganatsekwyagon survived into the 20th century as well – as reflected in a 1960s verse by the Toronto bank-clerk-poet Raymond Souster (also associated with the Montreal poets Irving Layton and Louis Dudek, in a venture known as Contact Press). The verse is called “On the Rouge”: I can almost see / my father’s canoe / pointing in from the lake, / him paddling, / mother hidden / in a hat … Lost finally, perhaps forever, / behind ferns swallowing banks … drifting the summer / labyrinths of love.

The less mysterious later 20th century consensus about the location of Teiaiagon, at Baby Point on the Humber River, may somehow reflect its ultimately thicker and more prominent history in the later 17th century.

A website on present-day Toronto neighbourhoods reports that “Baby Point’s rich history dates back to the 1600s when it was a prosperous Seneca Nation village.” In 1816 “the Honourable James [formerly Jacques] Baby” finally “settled on this peninsula … overlooking the Humber River.” His estate there “was a virtual Garden of Eden. A lush apple orchard occupied much of the land [on ground nicely prepared by the old Iroquois cornfields?], and salmon swam in the Humber River.”

The website goes on: “Baby’s heirs continued to live in Baby Point until 1910.” Then the site ultimately wound up in the hands of “developer Robert Home Smith who began developing the Baby Point subdivision in 1912.” Most of the resulting upscale housing for upwardly mobile Torontonians of the day was built in the roaring 1920s.

The website goes on: “Baby’s heirs continued to live in Baby Point until 1910.” Then the site ultimately wound up in the hands of “developer Robert Home Smith who began developing the Baby Point subdivision in 1912.” Most of the resulting upscale housing for upwardly mobile Torontonians of the day was built in the roaring 1920s.

The place still exudes a “virtual Garden of Eden”ambience in the early 21st century. And if you spend a gentle summer afternoon walking the eccentrically circular Baby Point Road in 2006, it can seem easy enough to sense some ghosts of Teiaiagon 330 years ago – with the 1920s houses of the local new-world bourgeois (or “booboisie,” as H.L. Mecken said) standing in for the village palisade, guarding tennis courts where Iroquois longhouses once stood.

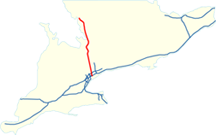

The first major technological update of the 17th century Toronto Passage or canoe portage, from Lake Ontario to Georgian Bay (via Lake Simcoe), was Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s own Yonge Street – the so-called “longest street in the world,” begun in the late 18th century. It remains the central backbone or main street of the Toronto metropolis today.

The first major technological update of the 17th century Toronto Passage or canoe portage, from Lake Ontario to Georgian Bay (via Lake Simcoe), was Lieutenant Governor Simcoe’s own Yonge Street – the so-called “longest street in the world,” begun in the late 18th century. It remains the central backbone or main street of the Toronto metropolis today.

A second key update was the mid 19th century Ontario, Simcoe & Huron Railway – from downtown Toronto to Georgian Bay. It was originally designed as a shortcut linking steamship routes on the lower and upper Great Lakes. It went on to become part of the later Canadian transcontinental network reincarnated as Canadian National Railways in the 1920s (and now one of the largest railway systems in North America – whose glory is reflected in the CN Tower on the present Toronto waterfront, still sometimes locally said to be “the tallest free-standing structure in the world”).

The most recent Toronto Passage technological update has been the multilane Highway 400, built in the second half of the 20th century. It runs due north from Toronto to the Georgian Bay and Muskoka cottage-country hinterland. It also finally links Toronto with the east-west Trans Canada Highway. You can still sometimes see trucks with Alberta licence plates on Highway 400, bearing present-day trade goods from the Canadian north and west. And then Highway 401 leads to Montreal (or, in the other direction, the old French fort at Detroit), and what is still quaintly known as the Queen Elizabeth Way ultimately leads to Albany and New York.

The most recent Toronto Passage technological update has been the multilane Highway 400, built in the second half of the 20th century. It runs due north from Toronto to the Georgian Bay and Muskoka cottage-country hinterland. It also finally links Toronto with the east-west Trans Canada Highway. You can still sometimes see trucks with Alberta licence plates on Highway 400, bearing present-day trade goods from the Canadian north and west. And then Highway 401 leads to Montreal (or, in the other direction, the old French fort at Detroit), and what is still quaintly known as the Queen Elizabeth Way ultimately leads to Albany and New York.

(All this can also help you remember that when the legendary North West Company fur trader and map maker David Thompson started a crucial last journey in the spring of 1811, on his quest to establish the Montreal-based Canadian fur trade along Canada’s Pacific Coast, he was accompanied by nine men – four French Canadians, two “Salish-speaking Sanpoil interpreters,” and “two Iroquois, Charles and Ignace.” And the North West Company itself was “the first organization to operate on a continental scale in North America.”)

From a more diffuse and still more intriguing perspective, those who wonder just where the almost dazzling multiracial diversity of Toronto today ultimately comes from could do a lot worse than look back to the 1660s, 1670s, and 1680s – when the modern metropolis had its earliest beginnings, on the Indian-European Middle Ground at Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon.

These two founding villages of early Toronto were intermittent homes to various aboriginal peoples of Canada and various Europeans, haphazardly thrown together in a new destiny by the early rumblings of a global economy. Ultimately there would also be Africans and even some Asians in the Canadian fur trade they were pioneering. La Salle first thought that the Mississippi River would take him to China. And “the Indians” were mistakenly called Indians because early Europeans in North America thought they were quite close to India, of course. (And nowadays India actually is at least much closer to North America than it used to be.)

Percy Robinson’s report that “two women were stabbed at Tcheiagon (Teiaiagon) in 1676 as the result of a drunken brawl” raises as well the prospect of what section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act 1982 calls the “Mtis peoples of Canada” – the mixed-race Indian-Europeans who would go on to form another unique human creation of the transcontinental Canadian fur trade of the late 18th and earlier 19th centuries. And in the summer of 2006 the Toronto Star published an interesting article by Andrew Chung on the “New Métis,” who are increasingly alive on the streets of the city today.

Finally (and at last), in 1930 the University of Toronto’s eminent fur-trade historian, Harold Innis (born and raised on a family farm in more or less the same southwestern Ontario as John Kenneth Galbraith) wrote in the conclusion to what is still almost certainly the most interesting and overall best book ever written on modern Canada’s past: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”

Finally (and at last), in 1930 the University of Toronto’s eminent fur-trade historian, Harold Innis (born and raised on a family farm in more or less the same southwestern Ontario as John Kenneth Galbraith) wrote in the conclusion to what is still almost certainly the most interesting and overall best book ever written on modern Canada’s past: “We have not yet realized that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.”

Three-quarters of a century later, Canadians are at least closer to this realization than they used to be, but they have still not taken the last decisive step. When they do, aboriginal rights and aboriginal land claims may become less thorny issues than the Six Nations land-claim protest is in the summer of 2006, at Caledonia, Ontario, in the Grand River valley.

Among many other things, what section 35 of the Constitution Act 1982 calls “the aboriginal peoples of Canada” were the earliest founders of the present-day country’s largest metropolis – in an exact and thoroughly demonstrable historical sense. Whatever else may or may not be true, they no doubt still deserve much more credit (and respect) – for this and many other contributions to modern Canada – than they have yet to receive from their fellow Canadians (in Toronto and every other part of the country as well)..

C.M.W. Marcel would like to thank his colleagues at the Linsmore Institute in Toronto.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND PAPER SOURCES

Arthur, Eric. Toronto: No Mean City. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1964, 1974.

Axtell, James. The European and the Indian: Essays in the Ethnohistory of Colonial North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

Benn, Carl. The Iroquois in the War of 1812. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

Braudel, Fernand. “History and the Social Sciences – The Longue Dure” (1958) in On History [Sarah Matthews, trans.] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969, 1980, 1982), 25-54.

Careless, J.M.S. Toronto to 1918: An Illustrated History. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 1984.

Colden, Cadwallader. The History of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, Which Are Dependent on the Province of New York, and Are a Barrier between the English and the French in That Part of the World. Toronto: Coles, 1972. Facsimile reprint of first edition in 1747.

Drake, James D. King Philip’s War: Civil War in New England, 16751676. Ahmerst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

Drury, E.C. All for a Beaver Hat. Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1959.

Eccles, W.J. France in America. Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1972, 1990.

Frost, Leslie M. Forgotten Pathways of the Trent. Don Mills: Burns and MacEachern, 1973.

Gentilcore, R. Louis, ed. Ontario’s History in Maps. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984.

Harris, R. Cole, ed. Historical Atlas of Canada, V. 1., From the Beginning to 1800. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987.

Heidenreich, Conrad E. “Seventeenth-century maps of the Great Lakes: an overview and procedure for analysis.” Archivaria, 6, (1978), 83-112.

_________________ . Huronia: A History and Geography of the Huron Indians, 16001650. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1971.

Innis, Harold A. The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1930, 1999.

_____________ . “An Introduction to the Economic History of Ontario from Outpost to Empire” (1934) in Essays in Canadian Economic History [Mary Q. Innis, ed.] (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1956, 1962), 108122.

Jaenen, Cornelius J., ed. The French Regime in the Upper Country of Canada During the Seventeenth Century. Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1996.

Jenish, D’Arcy. Epic Wanderer: David Thompson and the Mapping of the Canadian West. Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2003, 2004.

Konrad, Victor A. “Distribution, Site and Morphology of Prehistorical Settlements in the Toronto Area” in J. David Wood (ed.), Perspectives on Landscape and Settlement in Nineteenth Century Ontario (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada, 1975, 1978), 6-31.

_____________ . “An Iroquois frontier: the north shore of Lake Ontario during the late seventeenth century.” Journal of Historical Geography, 7, 2 (1981), 129-144.

Morison, Samuel Elliot. The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press, 1965.

Morse, Eric W. Fur Trade Canoe Routes of Canada / Then and Now. Ottawa: National and Historic Parks Branch, 1969, 1971.

O’Callaghan, E.B., ed. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1856.

Parkman, Francis. La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1869, 1904.

Sauriol, Charles. Pioneers of the Don . Toronto: C. Sauriol and Wadamaka Litho Ltd, 1995.

Robinson, Percy. Toronto during the French Rgime: A History of the Toronto Region From Brl to Simcoe, 16151793. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1933, 1965.

____________ . Papers. Archives of Ontario.

Schmalz, Peter S. The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991.

Souster, Raymond. As Is. Toronto: The Oxford University Press, 1967.

Steckley, John. “Toronto: What Does It Mean?” Arch Notes, May/June 1992, 2332.

Tanner, Helen Hornbeck, ed. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.

Tooker, Elisabeth. “The Five (Later Six) Nations Confederacy, 15501784” in Edward S. Rogers and Donald B. Smith (eds.), Aboriginal Ontario: Historical Perspectives on First Nations. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 79-91.

Toronto: fondation et prsence francophone de 1720 nos jours. Toronto: La Socit d’histoire de Toronto, 1991.

Trigger, Bruce G. The Huron: Farmers of the North. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969.

_____________ . “Early Iroquoian Contacts with Europeans” in Bruce G. Trigger (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, V. 15, Northeast (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 344-356.

_____________ . “The Original Iroquoians: Huron, Petun, and Neutral” in Rogers and Smith, Aboriginal Ontario, 4163.

_____________ and Gordon M. Day. “Southern Algonquian Middlemen: Algonquin, Nipissing, and Ottawa, 15501780” in Rogers and Smith, Aboriginal Ontario, 6477.

Webb, Stephen Saunders. 1676: The End of American Independence. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1984, 1995.

White, Randall. “Ferrall Wade at Toronto”. A Talk to the United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada, Governor Simcoe Branch, Toronto, 7 February 1996.

____________ and David Montgomery. Who Are We? Changing Patterns of Cultural Diversity on the North Shore of Lake Ontario. Toronto: The Waterfront Regeneration Trust, 1994.

White, Richard. The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 16501815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Williamson, Ronald F. and Christopher M. Watts, eds. Taming the Taxonomy: Toward a New Understanding of Great Lakes Archaeology. Toronto: eastendbooks, 1999.

Wilson, Edmund. Apologies to the Iroquois. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1960, 1992.

_____________ . O Canada: An American’s Notes on Canadian Culture. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1964, 1966.

_____________ . Upstate: Records and Recollections of Northern New York. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971, 1974.

Dear Mr./Mrs. Marcel,

One thing that was unclear to me is that, after explaining that the 5 Nations had routed the Iroquois on the North shore of Lake Ontario in the Beaver wars, and who were savvy with new technology, and who were eager to exploit and accumulate wealth, were all of the sudden (without explanation) themselves being routed by the Susquehannocks and moving to the same North shore of Lake Ontario?

Cheers,

Andrew

Thanks for your question Andrew.

I tried to quickly suggest one key difference between the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks to the south of the Five Nations and the Iroquoian-speaking Huron and Neutral to the north. Like the Five Nations, the Susquehannocks enjoyed a good supply of the latest military technology (guns and even cannon in the Susquehannocks’ case) from their closest European neighbours (the English in Maryland for the Susquehannocks). On Bruce Trigger’s reading in particular, the French were less forthcoming with the Huron and especially the Neutral to the north.

Somewhat more background on the Susquehannocks’ relations with the English in Maryland might have made this side of things a bit clearer. There was a period of hostility between these two parties. But in the 1660s they developed a rather extensive alliance. Along with English guns and cannon, some 50 Englishmen apparently fought on the Susquehannocks’ side against the Five Nations. It seems that the Five Nations were also temporarily weakened by an outbreak of smallpox (one of the diseases introduced to aboriginal peoples everywhere in the Americas by Europeans) in the mid 1660s, when pressure from attacking Susquehannocks prompted some Cayugas to flee to the north shore of Lake Ontario. (Which of course by this point was a vacant hunting ground.)

All the Iroquopian peoples of the wider region — from the Susquehannocks in the south to the Five Nations and the Huron and Neutral in the north — had similar strong military traditions of their own, and a long history of internal warfare before the arrival of Europeans. And it seems that in much of this history the Susquehannocks in the south were typically allied with the Huron and Neutral in the north, against the Five Nations in the middle.

Just why it was the Five Nations who developed such special eagerness to exploit and accumulate wealth after the arrival of Europeans, as you nicely put it Andrew, remains something of a mystery I think — perhaps ultimately linked to the mystery behind the subsequent eager economic expansion of the “Empire State†of New York (where the Five Nations lived). In any case commercial energy is not quite the same as military might.

As far as military might goes, by the mid 1670s the Five Nations’ detente with the French (also related to their settlements on the north shore of Lake Ontario, and the French-Iroquois treaty of 1667) had strengthened their position relative to the Susquehannocks. And then, as Bruce Trigger notes the “final breaking of the power of the Susquehannocks in 1675 did not come about as the result of an Iroquois victory, but because of an attack by European backwoodsmen from Maryland and Virginia.†in Bacon’s Rebellion, at the same time as King Phillip’s War further north.

So, you might say, the same European neighbours who helped the Susquehannocks against the Five Nations militarily in the 1660s finally, albeit rather inadvertently, helped the Five Nations against the Susquehannocks in the 1670s.

I hope all this makes things a little clearer for you — and certainly apologize if it only further confuses what is a complex story, that we still do not altogether understand in its full complexity.

Cheers, (Mr.) C.M.W. Marcel.

Dear Mr. Marcel,

Thanks for the response and thanks also for your article; it was as great read. I don’t know much about Canadian history despite being Canadian but am interested to find out more. I have a feeling that not many people know much about the origins of Toronto. I never learned any of this in school. One rather unrelated observation is that I couldn’t find a website for the Linsmore Institute anywhere. Also, the link to the Andrew Chung article is broken, although I’m going to contact The Star to request it.

Andrew

Thanks for letting us know about the broken Andrew Chung link Andrew. Hard to keep track of all these things as time goes by. It has now been replaced with a copy of the Star article that is still happily preserved on a Métis website. The Linsmore Institute is actually meeting next week, as it happens, and I will raise your website search in vain with the horses’ mouths then. CMWM.

[…] of the native groups indigenous to south-central Ontario, notably the Huron. C.M.W. Marcel’s 2006 Counterweights essay goes into interesting detail about the ephemeral Iroquois colonization of the northern shores of […]

[…] several kilometres upstream of Lake Ontario from the Humber River was occupied by Iroquois at the apex of their influence on the northern shore of Lake Ontario. Abandoned in 1689, this site eventually became included in […]