Is popularity of ‘Downton Abbey’ right, left, or something completely different?

Feb 4th, 2013 | By Randall White | Category: EntertainmentA few nights ago I caught up with the second latest episode of “Downton Abbey” (ie season 3, episode 4), as received here in the wilds of North America (and stored on the “Recordings” section of our current Bell Fibe cable TV service, here in the particular deep wilderness of Southern Ontario, Canada!).

I was prompted in part by Melinda Henneberger’s January 29 Washington Post piece on “The politics of Downton Abbey: Down with the patriarchy!” – which nicely describes our transatlantic version of this British “Victorian and Edwardian costume drama” as “the PBS hit about dressing for dinner.”

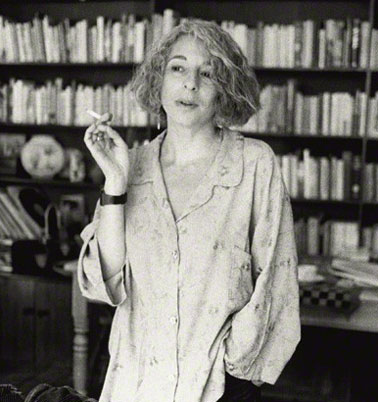

Ms Henneberger’s piece had itself reminded me of an earlier June 21, 2012 critique of “Downton Abbey” (and one other TV series and two related books), by Jenny Diski in the London Review of Books, entitled “Making a Costume Drama out of a Crisis.” Ms Diski’s piece had made me wonder whether I should even still be watching the PBS hit. (Which annoyed my regular TV watching partner, who likes “Downton Abbey” a lot.)

In any event, catching up with season 3, episode 4 (which I confess I did find quite gripping, technically at any rate) has prompted me to revisit both Melinda Henneberger’s and Jenny Diski’s rather different takes on the show. It may be that this has just added to my confusion. But it also suggests that anything which prompts so much debate must be onto something (maybe?).

To summarize at least the most obvious part of the essential argument up front, Melinda Henneberger starts with a critical concern about the “delighted belief” of “Fox & Friends” that the “popularity of ‘Downton Abbey’… shows our high esteem for job creators and our aspirational awe of the rich,” in the USA today.

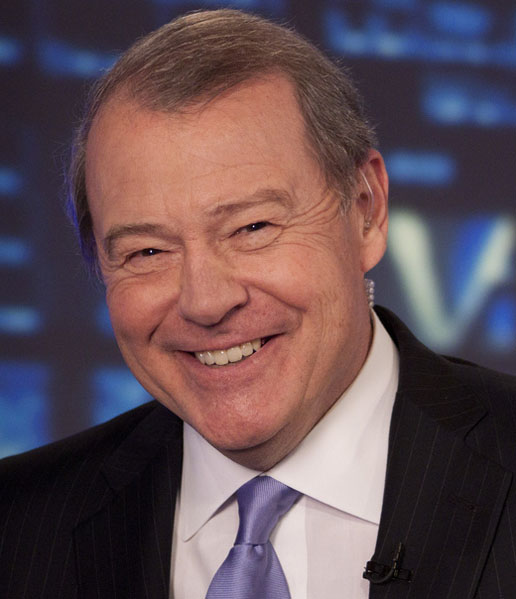

Fox TV’s Stuart Varney, Henneberger went on, argued that “Downton’s aristocrats are ‘very nice people’ The ‘entire town loves the rich guy who lives in the abbey,’ agreed Steve Doocy. Because according to Varney, his lordship and his family ‘create jobs, for heaven’s sake. They’re classy; they’ve got style. And we love them. That show is wildly popular; it poses a threat to the left, doesn’t it?’”

Ms Henneberger’s key response here, as best as I can make out, is that especially the more recent North American episodes of “Downtown Abbey”actually present an increasingly forceful and even feminist critique of both the snobbish foolishness of “the show’s paterfamilias, Lord Grantham,” and his palpable failings as a serious job creator. In Melinda Henneberger’s view, if the show has any underlying political message, it certainly poses no threat to the left.

Michelle Dockery who plays Lady Mary Crawley on Downton Abbey, at the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards in Los Angeles, January 27, 2013. Credit: Jason Kempin/Getty Images.

Jenny Diski, on the other hand, is on pretty much the same side of the ideological war as Melinda Henneberger, but almost seems to be agreeing with Fox TV in some crucial respects. She does not like “Downton Abbey” because, like other recent UK TV and literary concoctions, it comes from “purveyors of escapist fantasies of love and landed wealth,” who in turn (across the ocean at any rate) “come directly from the social world and political party that talks compulsively of ‘honest, hard-working families’ while giving us austerity and cuts in public spending for most, and tax breaks for the already wealthy and overpaid. The rich men and women in their castles are still dishing out charity to the poor men at their gate, but these days it is in the form of daydreams –Â circuses without bread.”

Why (some of) we children of the old global empire still have a soft spot for “ poshos swanning about in nice frocks” …

Further reportage from across the north Atlantic indicates that, over there, someone called “Barbara Ellen wrote a similar piece [to Jenny Diski’s] in the Observer back in January [2012], arguing that Downton just serves as retro porn for the middle classes during a recession.”

This past summer, that is to say, someone apparently called Eli, who wrote “A feminist defence of Downton,” went on to spell out yet another point of view: “So let’s get this straight: Downton is popular because we’re all longing for a time when the class system was neat and defined and everyone knew their place, because we like to watch poshos swanning about in nice frocks, and because we find comfort in portrayals of rich people being nice to poor people. I can’t be the only person who, as a lover of a good costume drama and a fan of Downton, is a bit insulted by all this. Diski and Ellen are both good writers and, Diski in particular does a good line in pithy take-downs. But I make them wrong on this.”

Cast of The Forsyte Saga, which “captivated the British public for 26 consecutive Sundays during 1967.” It appeared later in North America (and was repeated in the UK as well).

The more I think about it myself, the clearer it becomes to me that I don’t really know or even care all that much just what I think about this particular debate. I continue to watch “Downton Abbey” because my regular TV watching partner really does like the show, and because, although I have been much impressed by Jenny Diski’s critique (from back where the whole thing was actually made), I also think the show is a superior brand of evening soap operetta, from where the English language was first invented, and all that.

In my own narrow experience as well, I think back to the late 1960s and (over here at any rate, maybe?) early 1970s, when the British series “The Forsyte Saga” was being shown on North American TV. I had only recently started work at the time, in an office (with both male and female professional employees) where weekly PBS episodes of “The Forsyte Saga” were regularly discussed over coffee breaks and lunches. (Not quite as much as hockey games if just males were involved, but …) I don’t really have coffee breaks and lunches of this sort any more, and in some ways I miss them. Who knows? Maybe I also continue to watch “Downton Abbey” just in case this part of my earlier more youthful life should somehow revive.

The Fourth Earl of Minto, Governor General of Canada, 1898—1904. An illustration from a Vanity Fair supplement of the day.

Similarly, here in Southern Ontario (the second half of the “Western New York and Southern Ontario” to which our local PBS station caters), I grew up at a time when the trappings of the global British empire were more prominent than they are today. To take an example immediately at hand, I have just been reading a book about the history of Algonquin Park – an early”national” and then provincial park in the near Canadian wilderness. In explaining why one part of the park is named ”Minto Point,” the author elaborates somewhat on the career of the fourth Earl of Minto, who spent some time in Canada in the 1880s, as an assistant to Governor General Lansdowne, and then returned himself in 1898 as Governor General Lord Minto, who “travelled 113,000 miles throughout Canada during his time in office.”

All this had already begun to fade rather seriously during the decade and a half that immediately followed the end of the Second World War, when I was growing up in Southern Ontario. But enough of it was still in the air then to help me appreciate why substantial numbers of at least many English-speaking Canadians nowadays (and far from all of whom are of so-called British descent) still have a soft spot for British TV programs like “Downton Abbey.” If I finally have to choose (and be altogether serious) myself, I will come down on the side of Barbara Ellen and Jenny Diski …Â But …

At least some British (English? and other global?) aristocrats were admirable (and maybe still are?)

Emily Nussbaum (left) and Lena Dunham attend The New Yorker Festival 2012 Party at Andaz 5th Avenue, October 7, 2012.

The increasingly forgotten colonial folkways of we former British subjects in Canada, of course, do not explain why “Downton Abbey”is apparently just as or certainly very popular in Western New York and the rest of the USA today as it is in Southern Ontario and the rest of the Canadian wilderness (except, to some extent at any rate, French-speaking Quebec and its various eastern and western projections).

And yet Jenny Diski passes on some transatlantic intelligence that applies to we Canadians as much as it does to our American brothers and sisters: “in January 2012, Emily Nussbaum reviewed the first US showing of the second series of Downton Abbey in the New Yorker: ‘To let us know that we’re safely in the Masterpiece zone, Laura Linney, clad in a black cocktail dress, introduces each episode with a tense grin, as if welcoming us to a PBS fundraiser, which I suppose she is.’ In fact, she was explicating such complexities as ‘entail’ and ‘primogeniture’ to an American audience who had already been deemed to have too short an attention span to cope with the show, which had two hours cut from its British running time …”

John F. Kennedy gave his future wife Jackie a copy of The Young Melbourne – as an example of one of his favourite books. (She was apparently impressed!)

Thinking about this has finally led my mind to the small space on my surviving bookshelves occupied by two of the volumes I have most enjoyed reading (several times by now), in what has become a book-reading career of several decades. The first is called The Young Melbourne, and it was first published in the fateful year of 1939. I have the Grey Arrow paperback edition published in 1960. The book is about the younger life of the “2nd Viscount Melbourne… a British Whig statesman who served as Home Secretary (1830—1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835—1841) … best known for his intense and successful mentoring of Queen Victoria, at ages 18—21, in the ways of politics.”Among other things, this was one of John F.Kennedy’s favourite books (as attested by this, this, this, and that source!).

My second book here is another biography, entitled A Portrait of Charles Lamb. It was first published in1983. By this point I had become at least affluent enough to purchase a beautifully produced original hard cover edition, published by Constable and Company Limited at 10 Orange Street in London – with an assortment of intriguing illustrations depicting late 18th and early 19th century London, and an attractive colour frontispiece which reproduces “a detail from a Panorama of London, c. 1810, known as the ‘Rhinebeck’ Panorama.” This book is about the English essayist (and East India Company clerk), Charles Lamb, who was born in London, England in 1775 and died there, as geography is now reckoned, in 1834.)

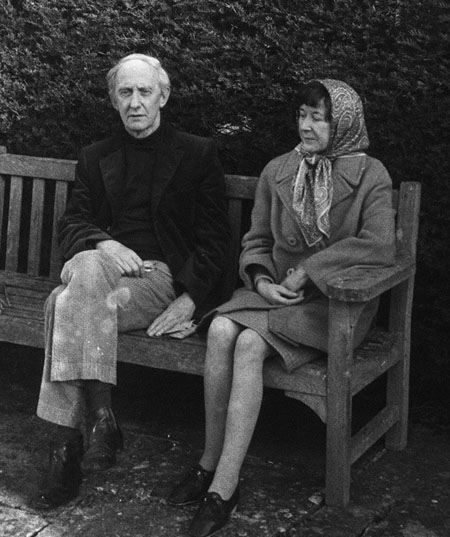

Both these books were written by David Cecil – “the youngest of the four children of James Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury and Lady Cicely (born Gore, second daughter of Arthur Gore, 5th Earl of Arran). His siblings were Beatrice Edith Mildred Cecil (afterwards Baroness Harlech), Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 5th Marquess of Salisbury (1893-1972) and Mary Alice Cecil (afterwards Mary Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire).”

David Cecil was born in 1902 at a real-life Downton-Abbey-like place called Hatfield House – “a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house was built in 1611 by Robert Cecil, First Earl of Salisbury and Chief Minister to King James I and has been the home of the Cecil family ever since. It is a prime example of Jacobean architecture and is currently the home of Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 7th Marquess of Salisbury.”

David Cecil was born at and grew up in Hatfield House. But “primogeniture” meant that it was his older brother who finally inherited the place. David nonetheless attended Eton College for what we benighted middle-class North Americans would call high school, and Oxford University. Then, as the current Wikipedia article on him explains : “From 1924 to 1930 Cecil was a Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. He made an impact as a literary historian with his first publication, The Stricken Deer (1929), a sympathetic study of the poet Cowper. He followed this with studies of Walter Scott, early Victorian novelists and Jane Austen … In 1939 he became a Fellow of New College, Oxford, where he remained a Fellow until 1969, when he became an Honorary Fellow … In 1947 he became Professor of Rhetoric at Gresham College, London, for a year; but in 1948 he returned to the University of Oxford and remained a Professor of English Literature there until 1970.”

David Cecil and his wife Rachel (née MacCarthy), 1966. By Janet Stone. National Portrait Gallery, London 2013.

David Cecil died on the first day of the new year, in 1986 – at the age of 83 and only a few years after the publication of A Portrait of Charles Lamb. What I like and admire so much about both this book and The Young Melbourne (published in Cecil’s late 30s) is that they are such beautifully written, compelling, instructive, and finely crafted examples of the non-fiction writer’s art. “Aristocracy” literally means rule by the best. We have lost our respect for its history because it came to have so much to do with who your mother and father were – and because its actions finally showed that, on balance, what was really best in human society had very little to do with heredity (or even what we now call “genes”). But hereditary aristocracies around the world have also sheltered at least intermittent efforts to reach for human excellence in such things as writing books (and even, The Young Melbourne suggests, very intermittently perhaps, in such strange arts and crafts as politics). And they have done this in ways that the strictly money-making kind of society we sometimes especially seem to have in North America – and that the United Kingdom bequeathed by Margaret Thatcher has perhaps emulated a little too much – does not quite appear to have found a replacement for yet. If there is any deeper political meaning to the current popular thirst for “Downton Abbey” – on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean? – my final tentative conclusion would be that it has something to do with all this …

Pamela Foster’s hit website on “Downton Abbey Cooks … Great food has a history”

I want to end these already far too long reflections by stressing that the pursuit of what is best in our all-too-short human lives on planet earth does not necessarily have anything to do with such exotic and often all too recondite, rarified (and even snobbish?) subjects as books and politics (or to cite another favourite book of mine, by a late, great Irish author, Writers and Politics).

From this angle, the altogether best explanation of the current popularity of “Downton Abbey” may lie in some related news I bumped into in my all too hasty research for these quick and dirty meditations here. And I am indebted in this context to a very recent article by Nadine Kalinauskas, that I stumbled across on the Yahoo Canada site.

Ms Kalinauskas notes that : “If your ‘Downton Abbey’ viewing party needs some era-appropriate food, a Toronto historian can help you out … Pamela Foster’s blog, ‘Downton Abbey Cooks,’ has become an online hit with an average of 3,000 visits a day and a Twitter following of 7,790. With everyone suddenly fascinated by all things related to the wildly successful British show, Foster’s early-20th-century recipes help bring a little British history into Canadian kitchens … ‘I hoped to inspire cooks to bring a touch of Downton elegance to their own Abbey,’ Foster, who has a history degree and works in corporate marketing, tells Radio.com.”

Going on to Pamela Foster’s site itself at first made me wonder a bit about all my theories above (or most of them at any rate). She explains that : “My husband, Lord D, and I are blessed to be able to spend a lot of time together and share the love for Downton. With his own English noble lineage, he loves the [to? the copy editor in me wants to ask, I hope not too impolitely?] look back in time, thinking of his ancestors, and yearning for the return of the days of decorum.”

Pamela Foster, mistress of Downton Abbey Cooks – who also loves to fish in near Canadian wilderness.

But then I remembered Ms Foster works in ”corporate marketing” and lives in Toronto (as I do myself – the live-in-Toronto part, that is). And I thought about how I often speak with at least part of my tongue in part of my mouth myself. And I was further reassured when I read further and discovered that Pamela Foster “learned to cook from my maternal grandmother who was not unlike Mrs. Patmore in stature, education and wit. Strict, demanding, but with a heart of gold. Both had to make do with available foodstuffs out in the countryside, but were able to pull off some amazing meals.”

This also makes me think of some concluding remarks from Melinda Henneberger’s January 29 Washington Post piece, that may ultimately add up to her wisest comments on the subject(s) at hand : “I also disagree with Varney [remember him – from Fox TV] that ‘the politics of Downton are very important, and it’s important that they are popular in America today’ … To me, our embrace of the show says far less about our political leanings than about our non-partisan love of a juicy tale, told in a way that’s beautiful to look at and enlivened by one of our greatest living actors, Maggie Smith.”

The reference to Ms Smith’s talents here, I might add, will please my regular TV watching partner. But I can’t help remembering as well that, here as elsewhere, Jenny Diski is not quite so impressed : She finds it “quite unlikely that Maggie Smith was much delighted with the leaden script of Downton Abbey. She seems throughout to be half-heartedly impersonating Maggie Smith playing an Edith Evans role: intoning Wildean wit comes easily to her, but she’s uncharacteristically wooden – the supposedly snooty cleverness just isn’t good enough.”

(And I think I almost agree with Ms Diski on this point too. Though I would necessarily defer to Ms Henneberger and my regular TV watching partner in making any altogether final judgments. The “return of the days of decorum” does remain important.)