The quixotic quest for a single national securities regulator in Canada .. maybe Ontario should bail out too?

Jul 15th, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: Canadian Provinces

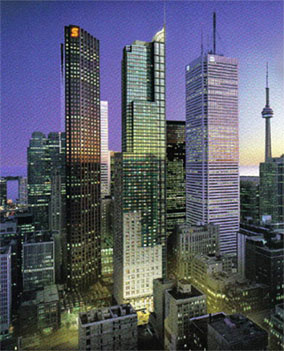

Early 21st century Toronto financial district, on a warm summer night. To the left, with a big red S on top, is Scotia Plaza – effective headquarters of the old Bank of Nova Scotia, whose official head office is still in Halifax.

The impossible dream of a single national securities regulator for Canada summarizes many intractable problems of our congenitally elusive Canadian national unity in the early 21st century. And as the Reuters agency has just explained: “Canada’s current minority Conservative government has come closer than any of its predecessors to launching” such an organization. But “it still faces formidable obstacles.”

The latest attempt to bell this cat, masterminded by “Doug Hyndman, a former securities regulator in British Columbia, says the new regulator,” to be known as the Canadian Securities Regulatory Authority or CSRA, “should have an office in each of the participating provinces.” (Already Quebec and Alberta have left the table, and Manitoba is dragging its feet – which leaves seven participating provinces, and presumably three territories?)

Some think this “move to decentralize the regulator may help win backing from dissenting provinces that are seeking to undermine the plan.” Yet, still other voices report, “Quebec and Alberta are expected to argue the latest proposal would not be substantially different from the current regime of having 13 different agencies, one in each province and territory.”

This view of the latest proposal is apparently shared by some traditional proponents of the single national regulator concept: “A controversial proposal to create a new national securities regulator without a head office simply replaces one patchwork system with another, critics of the plan say … It would be unthinkable to house the National Energy Board outside Alberta or the Canadian Wheat Board outside the Prairie provinces, said Matthew Mendelsohn, director of the Mowat Centre at the University of Toronto … ‘Yet we are perfectly happy to put financial regulation outside of the heart of activity simply because it’s Toronto’ … the proposed structure is ‘a mistake’ … it is essential to concentrate regulatory authority where market activity takes place.”

* * * *

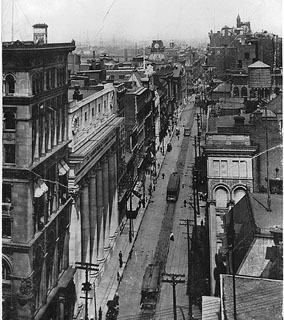

St. James Street, looking East, Montreal, QC, about 1910 – at the centre of the old Canadian financial metropolis.

An editorial in the Globe and Mail has urged a similar point of view: “Not so long ago, Montreal was a larger financial centre than Toronto, and Toronto may well eventually be surpassed by Vancouver or Calgary, in which case the CSRA’s head office – whether de facto or de jure – should then move west … Now, the work forces of Canada’s securities commissions range from Ontario’s 479 to Prince Edward Island’s three, which gives a rough but realistic estimate of where the bodies are needed.”

On the other hand again, the new decentralized “plan is a good first step in getting the provinces to buy into the idea, Louis Gagnon, a professor of business at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., told CBC News.” (Kingston, some will remember, has traditionally seen itself as a centre midway between Toronto and Montreal.) M. Gagnon, however, “added the lack of a head office is an issue that must be resolved.” And “I don’t see why Toronto would be the primary candidate.” He used “the example of the US, where the Securities and Exchange Commission is based in Washington … ‘There’s nothing that says the national market regulator is more effective … in exactly the same city as the largest national capital marketplace,’ he said.”

Of course, there’s still more. Bloomberg Business Week in the USA has just explained to its readers how “Canada is the only member of the Group of Seven nations without a national securities watchdog … ‘It makes pragmatic business sense for a head office to be in Toronto. It’s Canada’s financial capital,’ said Janet Ecker, president of the Toronto Financial Services Alliance” (and a former Ontario Conservative finance minister) … “‘I understand the politics but I’m disappointed that pragmatic business decisions appear not to be ruling the day…’”

Downtown Calgary 2005 : “Not so long ago, Montreal was a larger financial centre than Toronto, and Toronto may well eventually be surpassed by Vancouver or Calgary.”

On the other hand, yet again: “Raymond Bachand, finance minister from the French-speaking province of Quebec, has said the plan violates provincial jurisdiction and represents a ‘power grab’ by Toronto, the country’s financial hub. Quebec is challenging the federal government’s plan before the province’s Court of Appeal.”

And then, about a month ago, Alberta finance minister Ted Morton had already moaned that a “federal regulator, inevitably based in Toronto, would make it harder for Alberta’s junior oil and gas producers and other businesses to raise funds for growth and development.”

At some point, it’s hard not to wonder if all this doesn’t reflect a more fundamental problem with the Harper minority government’s broader “decentralized” approach to “national” policy-making in Canada. It probably isn’t much different from the already unusually decentralized Canadian federalism, with its unusually strong provinces, that we have already had, virtually since the late 19th century. So why bother trying to fashion some new kind of national policy that isn’t really a national policy? Why not just leave things as they are?

Even the Harper government’s current deadline for getting its new Canadian Securities Regulatory Authority up and running, with all those provinces and territories who do want to participate, is still some two years down the road. The hurdles that remain include “a question of constitutionality to be answered by the Supreme Court next year.” There are still those who feel that even a national regime involving seven provinces and three territories, with regional offices in each participating jurisdiction, would be at least somewhat better than the “current regime of … 13 different agencies, one in each province and territory.” And they may be right.

Vancouver, early spring 2007 : Canada’s most mystical and romantic city, on the Pacific coast at the foot of the mountains?

Even so, as a very last on-the-other-hand (yet again), Ontario itself may finally decide to stick with its own current regional regime, under which the Ontario Securities Commission’s 479 employees regulate what is at least for the moment the by far largest Canadian financial market (and even “the third largest in North America, after New York and Chicago”). As matters stand, it could be argued, the OSC is a kind of de facto national regulator in Canada. And the regional economic development interests of both Toronto and Ontario may ultimately be better served by sticking with this devil everyone knows – rather than experimenting with some highly decentralized “national” institution that would not do Canada’s most populous province any more good than it does Alberta or Manitoba or Quebec, and on and on and on …

Randall White is the author of a number of books on Canadian history and politics, including: Ontario 1610—1985: A Political and Economic History ; Voice of Region: The Long Journey to Senate Reform in Canada ; Ontario Since 1985; and Is Canada Trapped in a Time Warp?: Political Symbols in the Age of the Internet.