Waiting for the Iraq referendum .. two cheers for democracy?

Oct 13th, 2005 | By L. Frank Bunting | Category: Countries of the World George W. Bush may be, as Bill Maher memorably said on HBO TV last month, “a catastrophe that walks like a man” – who should now “do what you’ve always done best: lose interest and walk away.” It is also all too likely that if the Iraq Constitutional Referendum this coming Saturday, October 15 is even remotely successful, President Bush will be even less inclined to take Bill Maher’s good advice – or do anything else that almost makes sense.

George W. Bush may be, as Bill Maher memorably said on HBO TV last month, “a catastrophe that walks like a man” – who should now “do what you’ve always done best: lose interest and walk away.” It is also all too likely that if the Iraq Constitutional Referendum this coming Saturday, October 15 is even remotely successful, President Bush will be even less inclined to take Bill Maher’s good advice – or do anything else that almost makes sense.

And it is clear enough that the concept of the Iraq war as a quest for democracy in the Middle East was at best an afterthought, when all the other excuses for a dangerously rash and foolhardy military adventure had proved utterly beyond continued rational belief.Yet if you have any real-world faith in what the Canadian Constitution Act 1982 calls the “free and democratic society” – or even if you are just remotely concerned about the growing prospects for rampant political instability in the Middle East – you have to hope that the October 15 Constitutional Referendum in Iraq will succeed in some degree.

What is the referendum supposed to do?

The referendum is crucial to the so-called Coalition Provisional Authority’s rather haphazard plans to create a new democratic government for the State of Iraq – the one arguably forward-looking (or at least potentially redeeming) outcome of the US-led invasion of the country.

The referendum is crucial to the so-called Coalition Provisional Authority’s rather haphazard plans to create a new democratic government for the State of Iraq – the one arguably forward-looking (or at least potentially redeeming) outcome of the US-led invasion of the country.

This past January 30 “fewer than 60 percent of all registered voters” in Iraq elected members of a transitional National Assembly. As prescribed in the coalition’s Transitional Administrative Law, one of this Assembly’s key tasks was to “write the draft of the permanent constitution” for the new democracy. This task has now been more or less accomplished. And on October 15 the draft constitution will be “presented to the Iraqi people for approval in a general referendum.”

The referendum “will be successful and the draft constitution ratified if a majority of the voters in Iraq approve and if two-thirds of the voters in three or more governorates do not reject it.” (Iraq is currently divided into 18 governorates or provinces.) If “the permanent constitution is approved in the referendum, elections for a permanent government shall be held no later than 15 December 2005 and the new government shall assume office no later than 31 December 2005.”

On the other hand, if “the referendum rejects the draft permanent constitution, the National Assembly shall be dissolved. Elections for a new National Assembly shall be held no later than 15 December 2005.” This new National Assembly “shall be entrusted with writing another draft permanent constitution.” And on and on – into who knows just what kind of dark future?

On the other hand, if “the referendum rejects the draft permanent constitution, the National Assembly shall be dissolved. Elections for a new National Assembly shall be held no later than 15 December 2005.” This new National Assembly “shall be entrusted with writing another draft permanent constitution.” And on and on – into who knows just what kind of dark future?

However it may be officially interpreted in Washington, it seems clear enough that a successful referendum this Saturday, October 15 will merely keep the prospect of an Iraqi democratic experiment that is not totally out of control more or less alive. A rejection of the current draft constitution would constitute a palpable big failure for current US (and UK) policy, and rather dramatically increase the prospects of dangerous instability both inside Iraq, and throughout the wider Middle East. (And now in a context where last weekend’s tragic earthquake in Pakistan – and parts of Afghanistan – have already enhanced such prospects by other means.)

A successful referendum is also an almost certain pre-requisite for any subsequent more sensible policy of gradual withdrawal of US, UK, and other coalition military forces from Iraq.

The fragile federalism of the new democratic Iraq

According to the New York Times, “experts say” that Iraq’s new draft constitution will “probably” be approved by enough Iraqi voters on October 15. The main concern is with the provision that “two-thirds of the voters in three or more governorates” could derail the project. And this raises broader worries about the fragile concept of “federalism,” which apparently lies at the heart of the new democratic constitution that the transitional National Assembly has drafted (with, it seems clear, much help and prodding from the US federal government).

According to the New York Times, “experts say” that Iraq’s new draft constitution will “probably” be approved by enough Iraqi voters on October 15. The main concern is with the provision that “two-thirds of the voters in three or more governorates” could derail the project. And this raises broader worries about the fragile concept of “federalism,” which apparently lies at the heart of the new democratic constitution that the transitional National Assembly has drafted (with, it seems clear, much help and prodding from the US federal government).

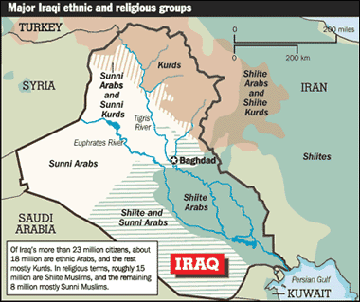

Very quickly, and broadly, Iraq as a modern political construct, dating from the end of the First World War, has always been a mixed bag of geographically concentrated ethnic and religious communities. So-called Shiite Muslim Arabs in the south account for about 60% of the population. Sunni Muslim Arabs in the central (and western) region account for about 17%. And a third group of Kurds (who are also Muslims), in the north and east, account for another 20%. (There are as well Turkomen, Assyrian, and Yazidi minorities, some of the last two of which are Middle East Christians – but none of these are large enough to play dominant political roles.)

Though Iraq is now divided into 18 governorates or provinces, in an earlier era it was divided into three large provinces (Basra in the south, Baghdad in the centre , and Mosul in the north), each dominated respectively by Shiite Arab, Sunni Arab, and Kurd majorities. And these three large southern, central, and northern regions have also come to play a key role in the concept of federalism embodied in the new draft democratic constitution of 2005.

The draft constitution “recognizes Kurdistan [in the north] as an existing federal region, but leaves the procedures for forming future federal units in the center and south to the next elected National Assembly.” This has a lot to do with a vain Bush administration plot to mollify the Sunni Arabs – who for the most part did not vote in the January 30 elections, and have participated only vaguely at best in the constitution-drafting process. (The process itself has largely involved a deal between the northern Kurds, with about 20% of the Iraq-wide population, and the southern Shiite Arabs, with about 60%.)

The Sunni Arabs, despite their mere 17% share of the Iraq-wide population, dominated the former authoritarian regime of Saddam Hussein. Many of them apparently do not warm at all to the concept of a federal Iraq with three (or more?) regions, in which the centre region that they continue to dominate would inevitably play a much reduced role than it has in the past. Among many other things, it is said, most of Iraq’s current producing oil wells are in the north and the south. And even with the exact definition of the regions beyond Kurdistan left to the future, “a new assembly with full Sunni Arab participation will still be dominated by an overwhelming pro-federal Shiite and Kurdish majority.”

The Sunni Arabs, despite their mere 17% share of the Iraq-wide population, dominated the former authoritarian regime of Saddam Hussein. Many of them apparently do not warm at all to the concept of a federal Iraq with three (or more?) regions, in which the centre region that they continue to dominate would inevitably play a much reduced role than it has in the past. Among many other things, it is said, most of Iraq’s current producing oil wells are in the north and the south. And even with the exact definition of the regions beyond Kurdistan left to the future, “a new assembly with full Sunni Arab participation will still be dominated by an overwhelming pro-federal Shiite and Kurdish majority.”

There would seem some prospect that there are mathematically enough Sunni Arabs in enough of the current 18 governorates to defeat the pro-federal constitution on October 15, under the provision that the document will be rejected if “two-thirds of the voters in three or more governorates”vote No. This prospect seemed real enough to the overwhelming pro-federal Shiite and Kurdish majority in the current National Assembly to prompt a recent attempt to change the rules, so that “two-thirds of registered voters – versus just two-thirds of those who actually cast ballots,” would be required to vote No.

This rule change would almost certainly have made “it impossible for the constitution to fail.” But it was abandoned “after a loud protest from Sunni Arabs, who called it a mockery of democracy,’ as well as the United Nations and US government.”

According to the New York Times: “Even if Sunni Arabs come out and vote against the document, experts say they would probably not make up the majority in enough provinces to derail the constitution” – even without the now abandoned rule change. Yet one big part of the drama that still surrounds the October 15 referendum involves the continuing prospect that the experts just may prove to be wrong. It at least remains possible that enough Sunni Arab voters finally will turn out to ensure that “two-thirds of the voters in three or more governorates”vote No, and defeat the draft constitution.

The “insurgency” and the continuing basic security problem

Another big part of the drama that still surrounds the October 15 referendum of course involves the continuing armed insurgency in strategic parts of the country. On Tuesday, October 11, e.g.: “Insurgents determined to wreck Iraq’s constitutional referendum killed more than 40 people and wounded dozens in a series of attacks … including a suicide car bomb that ripped apart a crowded market in a town near the Syrian border.”

Another big part of the drama that still surrounds the October 15 referendum of course involves the continuing armed insurgency in strategic parts of the country. On Tuesday, October 11, e.g.: “Insurgents determined to wreck Iraq’s constitutional referendum killed more than 40 people and wounded dozens in a series of attacks … including a suicide car bomb that ripped apart a crowded market in a town near the Syrian border.”

One side to this insurgency no doubt involves radical Islamist jihad thugs inspired by the likes of Osama bin Laden. Large enough numbers of these insurgents come from other parts of the wider region, outside Iraq. Their diffuse international cause is the same as that of the terrorists who flew planes into the World Trade center in New York, and bombed a train in Madrid, the subway system in London this past summer, and most recently a second restaurant frequented by western tourists in Bali. They have been attracted to Iraq by the rash and foolhardy US-led invasion. But they have no practical interest in the future of Iraq itself – or even, it seems, any coherent political agenda for any part of the world, beyond wild theocratic fantasies of destruction and religious and cultural revenge.

At the same time, it seems clear enough as well that another side to the insurgency in Iraq involves Iraqi Sunni Arabs who reject the new democratic constitution – and the prominent role it inevitably gives to Iraq’s Shiite Arab majority. And these insurgents are simply practising local politics by other means, at least partly because they lack the demographic muscle to make democracy work for them (at least in all of Iraq).

Rick Salutin in the Toronto Globe and Mail has recently urged that the term “insurgents” in this context “covers over something specific and unsettling: incipient civil war among Iraq’s Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish communities.” To some large enough extent the current insurgency in Iraq is about Sunni “conflict with the Shiite politicians who wrote the constitution, largely excluded Sunni interests and then, in a power play, tried to change the rules to make its passage certain – until the UN forced them to back off.”

Just what impact all sides of the continuing insurgency will finally have on the October 15 referendum remains unclear. But at least the most logical strong supporters of the new Iraqi draft constitution argue that, whatever else, its unique federalism offers the best hope now extant of ultimately defusing at least the Sunni Arab side of the insurgency, and the increasingly disturbing prospects of incipient civil war. (And of at last establishing the kind of internal security circumstances that would set the stage for some serious reduction in what does seem to be the increasingly dysfunctional presence of US, UK, and other coalition military forces.)

Just what impact all sides of the continuing insurgency will finally have on the October 15 referendum remains unclear. But at least the most logical strong supporters of the new Iraqi draft constitution argue that, whatever else, its unique federalism offers the best hope now extant of ultimately defusing at least the Sunni Arab side of the insurgency, and the increasingly disturbing prospects of incipient civil war. (And of at last establishing the kind of internal security circumstances that would set the stage for some serious reduction in what does seem to be the increasingly dysfunctional presence of US, UK, and other coalition military forces.)

On this view what the new federal Iraq has to offer the Sunni Arabs is finally the same thing it offers the Shiite Arabs and the Kurds – their own new federal region to dominate, in the central-western part of the country. (“And while current [oil] production is concentrated in the Kurdish north and Shiite south, all of Iraq’s regions have unexploited resources that are likely to produce considerable revenues for them in the future.”)

As wise as this view may or may not prove in the longer run, for the moment it appears to remain something sensible enough that most Sunni Arabs may only eventually adjust to and learn to love. As matters stand, many Sunni leaders still seem understandably obsessed by the reduction in their former Iraq-wide influence that any form of democratic constitution is bound to entail.

An in-some-quarters-much-touted new compromise announced by pro-constitution Iraqi leaders as late as October 12 “promises that the next Iraqi parliament, to be formed after elections in December, will set up a special committee to consider constitutional amendments,” especially regarding “three key provisions that deal with federalism, Iraq’s national identity, and the status of former members of Saddam’s Ba’ath Party,” that “Sunnis are anxious to change.” But the key problem here remains that in order to get any such amendments actually passed, Sunni leaders would still have to convince Shiites and Kurds, who will inevitably have much stronger democratic representation than the Sunnis in the next Iraqi parliament or National Assembly.

What does democracy in the Middle East finally mean … George W. Bush’s New Islamic Republic of Iraq?

Probably the key practical point is that if the October 15 referendum does succeed – at least insofar as it is not rejected by Sunni Arabs with two-thirds of the vote in three provinces or more, and is approved by a credible enough Iraq-wide majority (which is not deterred from showing up to vote by an increasingly fierce armed insurgency) – a fresh set of creative political circumstances will hopefully arise, within which all of Kurds, Shiite Arabs, and Sunni Arabs can start to more constructively fill in the current blanks in the new federal constitution.

Probably the key practical point is that if the October 15 referendum does succeed – at least insofar as it is not rejected by Sunni Arabs with two-thirds of the vote in three provinces or more, and is approved by a credible enough Iraq-wide majority (which is not deterred from showing up to vote by an increasingly fierce armed insurgency) – a fresh set of creative political circumstances will hopefully arise, within which all of Kurds, Shiite Arabs, and Sunni Arabs can start to more constructively fill in the current blanks in the new federal constitution.

Even on the most optimistic scenario, if this does happen many deep difficulties will of course remain. Ideally, quite remarkable (and in some quarters highly controversial) provisions for regional military forces in the new Iraqi federal constitution could help defuse the Sunni Arab side of the present insurgency, by allowing Sunni Arabs to provide their own security within their own federal region. (Which is presumably something like what the former US ambassador to Croatia Peter Galbraith means, when he argues that the new draft Iraqi constitution at least “provides for a more workable military strategy than the one to which the US is now committed.”)

On the other hand, as some critics have urged, the provisions for regional military forces in the new federal constitution might instead just help the combatants in a new Iraqi civil war get better organized. And presumably the most disturbing prospect of a real and not just incipient civil war in Iraq is that it just might spread to the wider Middle East region, with who knows just what incalculable and disturbing consequences?

(One thing the current situation in Iraq seems to make clear enough is that virtually the entire present political geography of the Middle East was rather haphazardly created in the wake of the First World War. And it was to no small extent designed around now obsolete European imperial interests – which, as in Vietnam, the old democracy in America seems to have once again ironically stumbled into defending after the fact. From one very radical point of view what many Iraq Sunni Arabs may actually most want to do is finally join with their brethren in such places as Syria, Jordan, and Egypt – and even Palestine too? – in some new United Arab Republic.)

(One thing the current situation in Iraq seems to make clear enough is that virtually the entire present political geography of the Middle East was rather haphazardly created in the wake of the First World War. And it was to no small extent designed around now obsolete European imperial interests – which, as in Vietnam, the old democracy in America seems to have once again ironically stumbled into defending after the fact. From one very radical point of view what many Iraq Sunni Arabs may actually most want to do is finally join with their brethren in such places as Syria, Jordan, and Egypt – and even Palestine too? – in some new United Arab Republic.)

Whatever happens, it already seems clear enough that insofar as the quest for a new democracy in Iraq does succeed, in some degree, the resulting new democratic state is going to look quite a bit different from anything anyone in Washington ever really wanted, or even contemplated.

As Peter Galbraith has also stressed the new “constitution states that Islam is the official religion of the state and is a basic source of legislation’ … More troubling is the constitution’s clause prohibiting any law that contradicts the established provisions of Islam.’ Since there is no agreement on what constitutes these established provisions,’ Iraqi secularists fear that this language will allow clerics to impose their own interpretation of Islamic law.”

The leaders of Iraq’s Shiite majority have also made it clear enough that their new federal region (or regions?) of the future, should the new constitution be ratified, will be very much of a democratic Islamic republic, with close ties to their Shiite brethren in Iran next door.

The big trouble of the George W. Bush who is “a catastrophe that walks like a man” in all this, as Peter Galbraith has pointed out as well, is that he is “not … well versed in the intricacies of Iraqi politics (or even its broad outlines).” Now he is reaping what he has sown, without ever seeming to have really known much at all about just what it was he was sowing in the first place.

In any case, still vaguely theocratic Islamic republics now do seem to be what you get when you start spreading democracy in the Middle East. (Which admittedly may not much bother those who already advocate a vaguely theocratic republic in the USA.) And at the moment supporting the October 15 referendum in the new democratic Iraq still does seem to be the most promising way of finally starting to get out of the appalling mess that George W. Bush’s (and Tony Blair’s) Iraq war has got all of the free world into, for better or for worse.

In any case, still vaguely theocratic Islamic republics now do seem to be what you get when you start spreading democracy in the Middle East. (Which admittedly may not much bother those who already advocate a vaguely theocratic republic in the USA.) And at the moment supporting the October 15 referendum in the new democratic Iraq still does seem to be the most promising way of finally starting to get out of the appalling mess that George W. Bush’s (and Tony Blair’s) Iraq war has got all of the free world into, for better or for worse.

(Or as the well-travelled British novelist E.M. Forster put the very largest point, as long ago as the early 1950s, Two Cheers for Democracy.)

UPDATES: According to press reports on Sunday, October 16 it is likely that final results expected later in the coming week will show a majority Yes vote for the new constitution, with no two-thirds of the electorate in at least three governorates or provinces voting No (although Sunni Arab majorities in two provinces actually may have turned out in some numbers to reject the document). Turnout generally has apparently been above 60%.

For a late October update on the referendum and the road ahead see The Asian Tribune. On October 25 it was reported that the draft constitution has officially passed: “Results released by the Independent Electoral Commission of Iraq showed that Sunni voters, who had sharply opposed the draft document, failed to produce the two-thirds “no” vote they would have needed in at least three of Iraq’s 18 provinces to defeat it … The commission, which had been auditing the referendum results for 10 days, said at a news conference in Baghdad that Ninevah province, had produced a “no” vote of only 55 per cent. Only two mostly Sunni provinces Salahuddin and Anbar voted no by two-thirds or more.”