Death of George Dryden (Diefenbaker?) : remembering the last prime minister of the old Dominion of Canada

May 5th, 2016 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

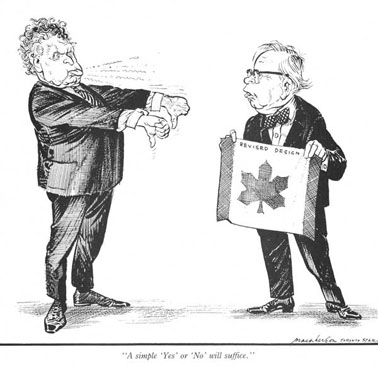

Duncan Macpherson cartoon on Dief the Chief’s dislike of Lester Pearson’s new Canadian maple leaf flag.

Inevitably, the sad death of the so-called “Diefenbaby,” George Dryden, highlights the career of his “likely” unacknowledged father, John George Diefenbaker.

For those not old enough to remember, Dief the Chief was a melodramatic prairie courtroom lawyer from Wakaw (and then Prince Albert), Saskatchewan. Somehow he became supreme leader of “my fellow Canadians,” 1957—1963 – and, whatever else, served faithfully as  the last prime minister of the old British Dominion of Canada.

Like many others, no doubt, I’ve been intrigued by Colin Perkel’s Canadian Press report on George Dryden’s death (as presented on the CBC News site). There is now apparently some fairly serious evidence that Mr. Dryden’s reputed father actually had two unacknowledged sons (only one of whom was Mr. Dryden).

Personally, however, even assuming all this is broadly correct, I think it just serves to remind us that Canada had special attractions for crazy-town politicians long before the late Mayor Ford brought fresh international attention to the big smoke in Toronto.

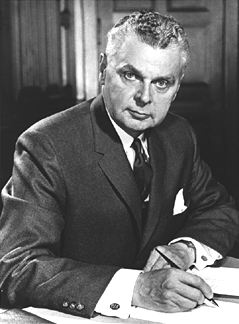

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker at May 1960 Commonwealth Prime Minister’s Conference in London, England.

Above all else, as already noted, John Diefenbaker was the last prime minister of the old Dominion of Canada. For me at any rate this best summarizes his ultimate significance in Canadian political history.

Yet it is part of the thickness of his public persona that there is more to his professional biography. He is not just the former prime minister who backwardly opposed Lester Pearson’s new independent Canadian maple leaf flag in the middle of the 1960s.

It is similarly one of the marvels of the world-wide web in the early 21st century that students of Diefenbaker Canadiana today have some excellent source materials immediately at hand …

1. Half a dozen key sources …

The selection of sources I’ve chosen for my Diefenbaker meditations here begins with four short newspaper articles – Â two from 2012 and two from 2013 :

Crawford Kilian, “Peter C. Newman’s Politics as Soap Opera,” TheTyee.ca, Â 5 Jan 2012 ; Jeffrey Simpson, “Making Canada’s past a slave to power,” The Globe and Mail, 4 May 2012 ; Â Allan Levine, “The defining Canadian political blockbuster, 50 years later,” National Post, 2 Oct 2013 ; and Pat Murphy, “Renegade in Power still tells a powerful story,” Troy Media, 15 Oct 2013.

For those prepared to take on a just somewhat longer reading assignment, there are at least two good biographical sketches online. The first (and shorter) is on the Historica Canada site called The Canadian Encyclopedia. It is by Patricia Williams, who has also written sketches of other Canadian Conservative politicians for Historica Canada.

Ms Williams is clearly an admirer of and even a partisan for Mr. Diefenbaker, while still trying to stay close to some kind of larger real world. If you keep this in mind, her crisp article provides a useful short outline of the highlights of the Chief’s career.

The second and much more heavyweight piece is by the historian and political scientist Denis Smith, who according to Jeffrey Simpson at the Globe (see above) “has written by far the best biography of the PC leader, Rogue Tory.” Smith’s much shorter but still long enough biographical sketch of “DIEFENBAKER, JOHN GEORGE, lawyer and politician” is altogether excellent.

It appears on the Dictionary of Canadian biography site. And this is a remarkable enterprise in its own right, “made possible by an imaginative and public-spirited bequest of James Nicholson, a Toronto businessman, who, at his death in 1952, left the residue and bulk of his estate to the University of Toronto for the purpose of creating a biographical reference work for Canada of truly national importance.”

2. Patricia Williams’s case for Diefenbaker

John Diefenbaker and Canada’s first female cabinet minister Ellen Fairclough in Prime Minister’s Office, 1960.

Patricia Williams states her view of the case for Diefenbaker right at the start of her Historica Canada sketch :

“Well known as a defence lawyer before his election to Parliament, Canada’s 13th prime minister was an eloquent spokesman for ‘non-establishment’ Canada both as a lawyer and as a politician. A supporter of civil rights for all, Diefenbaker championed the Canadian Bill of Rights and the extension of the vote to First Nations; he also played an important role in the anti-apartheid statement that led to South Africa’s departure from the Commonwealth in 1961.”

Ms Williams goes on : “Under the philosophical umbrella of ‘social justice,’ the Diefenbaker government restructured programs to provide aid to those in need. In addition to the Agricultural Rehabilitation and Development Act (1961), his government also established a Royal Commission on Health Services (1961) as well as the National Productivity Council (1963) – later named the Economic Council of Canada. The ‘northern vision’ that figured so prominently in the rhetoric of the 1957 and 1958 elections increased public awareness of the Far North and led to some economic development in that region.”

Queen and Yonge streets in Toronto, looking north on Yonge, summer of 1965 : “Eaton's and Simpson's department stores fly the brand new Canadian flag. Simpson's added a few of the traditional Union Jacks.” To keep Conservative politicians like John Diefenbaker happy.

Ms Williams notes as well that : “A charismatic and popular speaker, Diefenbaker could also be a divisive force within the Progressive Conservative Party. Moreover, he has been criticized for his indecision concerning nuclear missiles on Canadian soil (as well as strained relations with American President John F. Kennedy) and for his cancellation of the Avro Arrow project.”

These last words of course add up to a pretty lame and massively incomplete summary of the case against Diefenbaker, as entertained by the legions of his critics. What I find most misleading myself is Patricia Williams’s stress on Dief as “an eloquent spokesman for ‘non-establishment’ Canada.” In some ways he was a very aggressive supporter of some of the oldest British North American political establishments still lingering on the Canadian scene of his day. His most obvious mistake on this front almost certainly was what Ms Williams alludes to when she writes that he “also argued vigorously (if unsuccessfully) against Pearson’s proposal for a new Canadian flag in 1964.” But there were others as well…

3. Introducing Denis Smith’s deeper treatment

Denis Smith’s biographical sketch of Canada’s 13th prime minister weighs in at just over 10,000 words. It has room to fill in a lot of blanks, and offer a more balanced picture of this particular intriguing (and no doubt more twisted than usual) Canadian political life.

John George Diefenbaker was born in 1895. He grew up in a family of educated but struggling underpaid rural school teachers and local officials, at first in the more northerly reaches of Southwestern Ontario (Alice Munro country) and then in Saskatchewan.

In Diefenbaker’s mid-teens his father finally landed a decent job at the customs office in Saskatoon. It would last until his retirement a quarter century later. John himself “attended the Saskatoon Collegiate Institute for two years. With his mother’s encouragement he entered the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon in the autumn of 1912 to study arts and law.”

After various further academic adventures, and some not entirely clear experience in the Canadian forces’ 196th (Western Universities) Battalion during the First World War, John George Diefenbaker was called to the bar by the Law Society of Saskatchewan in June 1919. At this point, at the age of 24, he also had three degrees from the University of Saskatchewan – BA, MA (political science and economics), and LLB.

As Denis Smith explains : “He opened his first office in Wakaw, 40 miles north of Saskatoon. Wakaw was a thriving market town of 400 in a farming district settled by immigrants from central and eastern Europe. It was on the district court circuit and had easy access by rail and road to high court sessions in Saskatoon, Prince Albert, and Humboldt. The tall, thin young man with deep blue eyes and wavy black hair, dressed soberly in a dark three-piece suit, made an immediate and striking impression in the small town.”

Diefenbaker House and Museum in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan today. It seems that the Chief actually lived here c. 1947—1957. And then rented it out for another 20 years. Note how even his old house has nowadays surrendered  to the new Canadian flag he fought so hard against.

In this particular place it probably didn’t hurt that “Diefenbaker” was a central European name either. In any case the young Dief developed an increasingly successful legal practice, defending the interests of the farming community surrounding Wakaw from the various wider corporate and governmental pressures regularly brought upon it.

As further explained by Denis Smith : “Although Diefenbaker’s civil case list grew, his reputation would be founded on his record as a criminal defence lawyer. In the courtroom he discovered and honed his dramatic genius. He mastered juries with his powerful and edgy voice, his penetrating stare, his waving arm and accusatory finger, his ridicule and sarcasm, and his command of evidence and the law.”

By 1924 he had moved his main office to nearby Prince Albert – the third-largest city in Saskatchewan and the province’s “Gateway to the North.”

4. The long road to the 1957 election

Denis Smith still further explains that when John Diefenbaker began his studies at the University of Saskatchewan, he “already had a political career in mind; in later years his family recalled that his ambition to be prime minister had been expressed before he was ten.”

John Diefenbaker wins an election at last – as new Member of Parliament in Ottawa for Lake Centre, Saskatchewan, May 1940.

What is striking in Smith’s account from here is just how long (and persistent) a political apprenticeship Dief served . He first ran for the Conservative party in the Saskatchewan riding of Prince Albert in the federal election of 1925. He was defeated – as he would be four more times, at all of federal, provincial, and municipal levels of government. At last he won the federal seat for the more southerly Saskatchewan riding of Lake Centre in 1940. And he would not be defeated as a Member of Parliament again – winning Lake Centre two more times and then Prince Albert 10 times, all the way to 1979!

Dief similarly first ran for the leadership of the federal Conservatives in 1942, in a race won by John Bracken, the Progressive premier of Manitoba who would help rename the party “Progressive Conservative.” (Probably also a wise name adjustment, given growing progressive wartime sentiment among electorates in all such places as the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, and so forth.) Dief ran unsuccessfully for the leadership again in 1948, losing this time to the premier of Ontario, George Alexander Drew.

Finally (and again, with dogged effort and persistence) Dief ran for the federal Progressive Conservative leadership yet again in December 1956. This time, Denis Smith explains : “Despite brief efforts to create a ‘Stop Diefenbaker’ campaign in Ontario, he was the instant favourite over his opponents,” and he “won a decisive victory on the first ballot.”

The next two marvellous years marked the high tide of John George Diefenbaker’s political career. By the start of 1957 Louis St. Laurent’s federal Liberals – who had been in office for some 22 consecutive years – were starting to show a few too many signs of wear and tear. In an election called for June 10, 1957, the “Tories ran a campaign centred on their new leader, who attracted large crowds to rallies and made a strong impression on television.”

On election day the Diefenbaker Conservatives won 112 seats in Ottawa, with 38.5% of the cross-Canada popular vote, compared with only 105 seats for the St. Laurent Liberals with 40.5% of the popular vote. This was enough to give Dief the Chief a minority government, with himself as first Conservative prime minister of Canada in 22 years. (Even if the operative party label at this point, and especially under John George Diefenbaker, was “Progressive Conservative.”)

5. Highlights from the gospel according to Denis Smith …

At this juncture I’ll just turn the story over to Denis Smith, from his excellent Canadian Dictionary of biography article of just over 10,000 words :

* “In his administration’s early days Diefenbaker made a public commitment to divert 15 per cent of Canada’s foreign trade from the United States to the United Kingdom. The promise would remain unfulfilled despite his government’s continuing efforts to lessen dependence on the American market and to promote trade with the British Commonwealth. Beyond this initial misstep, the new government proceeded boldly with an ambitious legislative program of farm price supports, housing loans, aid for development projects across the country, tax reductions, and increases in old-age pensions and civil service salaries. Public opinion polls showed strong support for the new government. When the Liberal leader, Lester Bowles Pearson, moved a motion of no-confidence proposing that the Conservatives hand power back to the Liberals, Diefenbaker seized the occasion to request a dissolution of parliament for an election in March 1958.” (March 31, 1958 in fact.)

* “Diefenbaker’s 1958 platform was a simplified and more exuberant version of the party’s 1957 program, involving a new vision of the nation both economic and spiritual. He preached a populist, secular faith. ‘Everywhere I go,’ he declared, ‘I see that uplift in people’s eyes that comes from raising their sights to see the Vision of Canada in days ahead.’ Diefenbaker’s rhetoric caught the public mood. His campaign swept the country in a wave of euphoric enthusiasm. The posters called for voters to ‘Follow John’ and the electorate responded by granting the Conservatives an astonishing 208 of 265 seats, including 50 in Quebec. In his victory speech Diefenbaker declared that ‘the Conservative Party has become a truly national party composed of all the people of Canada of all races united in the concept of one Canada.’ His ‘Vision’ had raised public expectations beyond the possibility of satisfaction. He would need rare skill and good fortune to avoid a crashing descent from those heights …”

* “Diefenbaker’s entire adult life was aimed at a political career. He was moved by ambition and a sense of injustice that was both personal and regional, a determination to succeed at the centre of Canadian politics in Ottawa and in doing so confirm the equal rights of those he believed had been excluded from power and influence in Canada. His attitudes were shaped in the 1920s and 1930s, when Canadian public life was dominated by a privileged circle of Ontario and Quebec politicians in the Liberal and Conservative parties. With his personal and western preoccupations, however, he failed to sense the potential grievances of the French-speaking Canadian minority, who felt similarly excluded from a full role in national life.”

* “Possessed of a rare determination that was reinforced rather than dulled by early slights and defeats, Diefenbaker had nurtured a dramatic and corrosive talent as a criminal defence lawyer which served him well as a member of the opposition, though less well as a member of government. He was a British Canadian with a sentimental attachment to the imperial connection and to Canada’s parliamentary institutions. His convictions on welfare and employment policy were shaped in the 1940s by his experience of the great depression on the prairies and were broadly shared by colleagues in the Liberal and CCF parties. In his approach to fiscal and monetary policy, on the other hand, he remained an instinctive conservative, never fully absorbing the lessons of Keynesian economics.”

* “By temperament Diefenbaker was never a team player. Once he was in office, it was quickly evident that he could not produce harmony in his cabinet, nor could he master the technical complexities of financial, defence, and foreign policies. He was overwhelmed by the problems of administration and was relieved by the prospect of escape into the House of Commons or onto the hustings, where his talents as a populist preacher could be exuberantly exercised. There, he was melodramatic and overbearing, appealingly comical, whimsical, and sarcastic. He put on a great show. He was one of the last pre-television democratic leaders, who sought direction and self-confidence by face-to-face and intuitive connection with his voters rather than by polls, focus groups, and opinion management. He nursed resentments and in his later adversity his sense of isolation gave rise to dark visions of persecution and conspiracy. In politics he had little more than two years of success in the midst of failure and frustration, but he retained a core of deeply committed loyalists to the end of his life and beyond. The federal Conservative Party that he had revived remained dominant in the prairie provinces for 25 years after he left the leadership.”

6. Some very last thoughts on the last prime minister of the old British Dominion of Canada

When did he finally leave the leadership? Jeffrey Simpson at the Globe has summarized all this in a perhaps less friendly way than either Patricia Williams or Denis Smith :

“Mr. Diefenbaker was a weak prime minister, or at least that’s what Canadians came to believe after seeing him in office for a while. They handed him the largest majority then recorded in Canada in the 1958 election. Halfway through its mandate, his government was tearing itself apart, and Mr. Diefenbaker was flailing and failing … By 1962, with the cabinet in revolt, his party was reduced to a minority. A year later, Canadians booted him and the Progressive Conservatives from office. It took four excruciating years to drag Mr. Diefenbaker from the party leadership.”

Meanwhile, I remember that John George Diefenbaker was also prime minister of Canada from the time I was 12 to 18 years old. In one all-too-human sense at least, I have a little of the same warmth towards him that I have towards myself as a confused and crazy teenager. And I remember as well that I saw him speak in person, I think at Varsity Arena in Toronto, sometime in what must have been 1965 when his days as prime minister had ended. I went with youthful lefty and other friends because he was still said to be an entertaining speaker, whatever else. See this Canadian legend while you can, etc.

I recall that I saw the first federal New Democrat leader Tommy Douglas speak in person too, around the same time – but at Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto, I think. And one of Mr. Douglas’s lines of the day about Canada was : “John Diefenbaker proved anyone can be prime minister.”

I noticed just over the past few days that this view of things was more positively reflected in one of the chief’s very own declarations, which I picked up from the rotating quotations on the present-day website of the Diefenbaker Canada Centre at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon : “They criticized me sometimes for being too much concerned with the average Canadian. I can’t help that. I’m just one of them.”

To me another of the rotating John Diefenbaker quotations from the Diefenbaker Canada Centre website summarizes quite a lot about his career : “Catch the vision. Catch the vision of the kind of Canada this can be. We ask you not to follow the path of defeatism and fear, not the concept of igloo to igloo. I’ve seen this vision: I’ve seen this picture of Canada.”

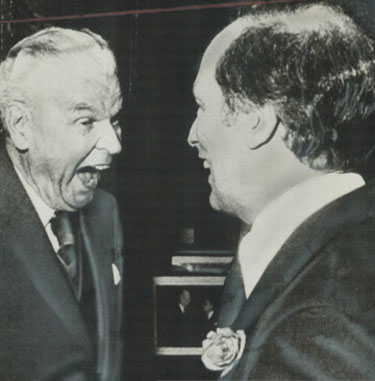

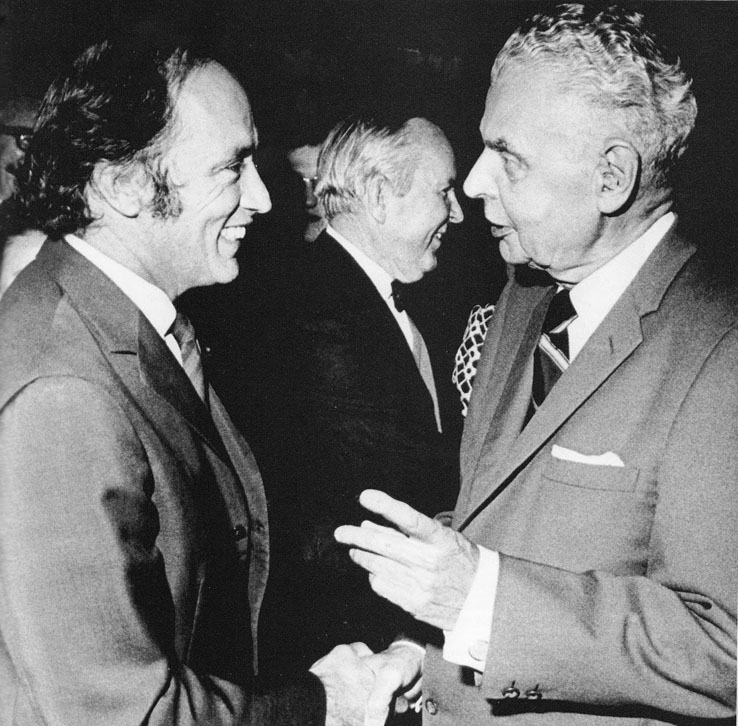

John Diefenbaker and Pierre Trudeau share a laugh, about something. It would be interesting to know just what!

This northern vision rhetoric that seems to have played such a big role in the triumphant 1958 election is – like the constitutionally un-entrenched (and not very enforceable) Diefenbaker Bill of Rights – something that it would finally take Pierre Trudeau to breathe some serious life into. (And then of course there’s “igloo to igloo.” Apart from anything else, nowadays some might call that progress. Traditional Inuit culture was one of the survivalist marvels of a world we have sadly lost in the far north. )

In a few ways Prime Minister Diefenbaker did hint at a few themes of the new Canada that began to rise, ever so gently and gradually, in the 1960s. But, as the great flag debate with Prime Minister Pearson finally made altogether clear, at bottom John George Diefenbaker looked to the past not the future. He was the last prime minister of the old British Dominion of Canada. (And in 1970, worried about just what the new age of Pierre Trudeau might finally bring, one of his executive assistants founded the Monarchist League of Canada.)

[…] in opposition, he had forcefully opposed the design for what became our national […]