Electing governor general is only option that finally makes sense

Apr 14th, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: Canadian Republic

Her Excellency the Right Honourable Michaëlle Jean, Governor General of Canada, speaks during the Art Matters forum on March 28, 2008, at Rideau Hall in Ottawa.

UPDATED MAY 2. Three weeks ago it seemed clear that Stephen Harper would not be extending the excellent Michaelle Jean’s customary five-year term in office. He would instead appoint a new Governor General of Canada soon enough – at the latest before Mme Jean’s official best-before date expires at the end of September.

Today we learn that the “Canadian secretary to the Queen” has consulted [official opposition leader Michael] Ignatieff on a successor at Stephen Harper’s request.” And Mr. Ignatieff has urged that “Ms. Jean has done a superb job. I am calling on Stephen Harper to reconsider his decision to replace her.” Mr. Ignatieff wants Governor General Jean’s term extended – as was done in the cases of such previous holders of the office as Roland Michener, Jeanne Sauve and Adrienne Clarkson.

Meanwhile, even some US media have by now picked up the story that the most popular candidate to replace Governor General Jean among we the great unwashed is apparently “the original Capt. Kirk, William Shatner … A Facebook campaign is calling for Shatner, a native of Montreal, to be appointed to a five-year stint as Governor General of Canada … More than 40,000 people are supporting” this of course not entirely serious campaign. (In fact there are 44,765 supporters, as of 3 PM ET today, May 2, 2010. One of the crowd, Brigitte Gervais, has posted: “My hero! Who wouldn’t want Capt. Kirk as their Governor General?”)

All this is suitably (and ceremonially) entertaining, as it probably should be. Yet if you are among the “65 per cent of Canadians” who think that Canada’s now strictly symbolic ties to the British monarchy “should be severed” at the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II (as I certainly am myself), it can easily seem almost entirely beside the point. The key issue for strengthening our contemporary Canadian democracy – and taking the final step in “the long process of decolonization that Canada has undergone since 1867”–Â is not who is going to be the next governor general, but how he or she will be chosen.

For the past 80 years or so the governor general has been effectively appointed by an inevitably partisan prime minister of Canada, all by himself. Intriguingly enough, we now learn that Mr. Harper has moved to somewhat vaguely consult the leader of the official opposition as well – a practice for which there is apparently some precedent during the regime of the last Canadian prime minister from Alberta, R.B. Bennett. But what makes most sense, for the time just ahead that we need to prepare for today, is a governor general chosen (in a suitably circumspect parliamentary democratic way) in some form of popular election, by the modern sovereign Canadian people themselves. (Not necessarily Captain Kirk, of course, but … )

And, though he is no doubt unlikely to admit or even recognize it, Mr. Harper already has a practical option of this sort in his bag of still unadopted “step-by-step” Senate reform tricks (or at any rate had, until the most recent tabling of his government’s Bill S-8 – a subject on which I hope to have still more to say very soon). Â This involves an interim approach to “consultations with electors on their preferences for appointments” to the office of governor general, that could at least move us closer to the Canadian future of our strongest and best angelic dreams.

Origins of appointment by Canadian prime minister

On one view of Canadian history the present office of governor general predates the British monarchy, and stretches all the way back to Samuel de Champlain, first Governor of Canada or New France, 1627—1635. This is a so-called “inauthentic depiction of Champlain” by the 19th century artist Théophile Hamel. Apparently no authentic portrait is known to exist.

As matters stand, the governor general formally represents the Queen in Canada. But the most straightforward way of cutting ties to the monarchy is to just have the governor general take over the Queen’s role in theory as well as practice, at the end of the Queen’s reign.

For virtually all practical purposes, the Governor General of Canada has already taken over the constitutional role of the British monarch in practice, at the behest of the Queen’s father in 1947 – also the date of the first Canadian Citizenship Act, which first created the official status of a post-colonial “Canadian citizen,” as opposed to a “British subject” resident in Canada.

From this point of view, the main problem with our present “vice-regal” arrangements in Canada is the method by which governor generals are currently selected.

From the start of the present confederation in 1867 down to the so-called Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canadian governor generals were appointed by the British monarch, on the advice of British prime ministers. Since the Statute of Westminster – which confirmed that self-governing British dominions were completely autonomous from the United Kingdom – Canadian governor generals have been (formally) appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the Canadian prime minister. (And, some would stress, this practice took effect informally after the Imperial Conference of 1926, which first opened the door, as it were, to the 1931 Statute of Westminster.)

An increasingly dangerous recipe for constitutional crisis?

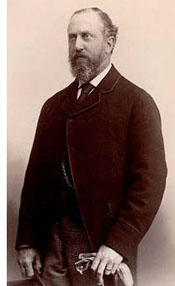

Frederick Arthur Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby KG, GCB, GCVO, PC, Governor General of Canada, 1888—1893. To later Canadians he left the name of Stanley Park in Vancouver – and most famously, of course, the Stanley Cup.

In the 1930s – and from then to the 1960s, say – having the Governor General of Canada effectively appointed by the Canadian rather than the British prime minister in this way probably was a mark of Canada’s long journey “from colony to nation.” The point was stiffened in 1952, when Canadian prime ministers began to appoint actual Canadian citizens, as opposed to British aristocrats, to the office – starting with Vincent Massey, a scion of the Massey-Harris agricultural machinery fortune, who still did his best to look like a British aristocrat.

More recently, however, appointment even by Canadian prime ministers has seemed an increasingly dodgy accident of a haphazard history, that only aids and abets the increasingly lamentable and democratically unaccountable centralization of federal government power in the office of the prime minister. (What would we think of the British system in the land of the Mother of Parliaments itself, eg, if the prime minister of the day were empowered to choose a new king or queen every five or so years?)

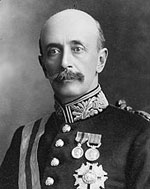

Albert Henry George Grey, 4th Earl Grey, GCMG, GCVO, PC, Governor General of Canada 1904—1911 – and the man who bequeathed the Grey Cup to Canadian football.

Moreover, with the current run of minority governments in Ottawa – raising more frequent prospects that the governor general must exercise the usually quiescent reserve powers of the crown, to resolve parliamentary disputes – appointment by Canadian prime ministers alone has arguably become an increasingly dangerous recipe for constitutional crisis.

As the eminent Canadian parliamentary authority C.E.S. Franks has recently explained, in the self-proclaimed national newspaper of Canada, there are some very good reasons to “wonder why the choice of a governor-general who might well at some time have to reject the advice of a prime minister over an important issue remains solely in the hands of the prime minister, an interested party. There are better ways to choose our head of state.”

Why elections make the most sense …Â and won’t make the still essentially ceremonial governor general’s office too powerful

Vincent Massey, Governor General of Canada 1952—1959: the first holder of the modern office (since 1867) who was not a British aristocrat, and the last who looked like he was – as more or less first said by the Winnipeg wit Larry Zolf.

The experience of various former self-governing British dominions (and outright colonies) since the end of the Second World War (or even the late 1930s) has suggested a variety of “ better ways to choose our head of state” in so-called Westminster-style parliamentary democracies. At the same time, the failed 1999 Australian referendum on replacing the British monarchy suggests that, in Marshall McLuhan’s global village at large, the best-before date on the, so to speak, most conservative of these options has already expired.

The most progressive (and democratic) option is to have the head of state directly elected (more or less) by the sovereign people. The failed 1999 Australian referendum – which proposed indirect election by already-elected politicians instead – also suggests that popular election is likely to be the most palatable option for democratic voters in the early 21st century.

The customary objection to a popularly elected head of state in a parliamentary democracy like Canada is that it would make the holder of the office not just more credible and legitimate in the eyes of the electorate, but more powerful than an essentially ceremonial head of state in a Westminster or British-style parliamentary democracy ought to be. Probably the best answer to this objection is that the present-day Westminster or British-style parliamentary democracy of the Republic of Ireland has had a (more or less) popularly elected ceremonial head of state since 1937 – and the office has remained essentially ceremonial.

Ray Hnatyshyn, born in Saskatoon, cabinet minister in the Conservative governments of Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney, and then Governor General of Canada, 1990—1995. He opened up Rideau Hall to the public, and “was praised for raising the stature of Ukrainian Canadians.”

Part of the reason for Ireland’s success here lies in what might be characterized as a quite conservative nomination process for head of state elections (which can sometimes mean that there is no election at all – if only one candidate is nominated). In Canada’s case the method of indirect election by members of federal and state parliaments in the present-day Westminster or British-style parliamentary democracy of the Republic of India (since 1950) may also have some special interest.

A popularly elected Canadian head of state, with candidates nominated through some process involving both federal and provincial legislatures, in other words, may be especially well-suited to Canada’s quite decentralized modern federation, with both strong provinces and a strong (enough) federal government in Ottawa. This might make particular sense if Canada were to follow the strict legal letter of the present Constitution Act 1867, and have provincial lieutenant governors actually appointed by the elected successor to the present office of governor general or “de facto head of state” – as opposed to having provincial lieutenant governors effectively appointed by the federal prime minister, as happens now.

(Some will ask, what about the lieutenant governor of Quebec? Others will urge that the figurative notion of the British monarch in right of particular provinces somehow secures provincial sovereignty. There is of course room for further debate. But it is worth stressing that as matters stand now, under the so-called Canadian constitutional monarchy, in practice the lieutenant governor of Quebec and every other province is appointed by the federal prime minister. And it is hard to see how this in any way secures provincial sovereignty. Having the appointments made by a popularly elected head of state, nominated by federal and provincial legislatures, would at least do more for provincial sovereignty than what we have now!)

Adapting PM Harper’s interim or step-by-step Senate election proposal to the office of governor general .. an idea whose time ought to have come

Stephen Harper and Bert Brown, the one elected senator he has managed to appoint, chosen by the voters at an Alberta provincial election.

In the early 21st century the almost certainly best argument the dwindling fraternity of Canadian monarchists has for perpetuating the British monarchy in Canada beyond the reign of Queen Elizabeth II is that, as a practical matter, the constitutional process required to change the monarchy’s role is so arduous as to make the real benefits of such a change not worth the trouble it would take to achieve.

The crux of the issue here is section 41 of the Constitution Act 1982, which prescribes that “An amendment to the Constitution of Canada in relation to … the office of the Queen, the Governor General and the Lieutenant Governor of a province” must be “authorized by resolutions of the Senate and House of Commons and of the legislative assembly of each province.”

In fact, agreement on constitutional issues by the Canadian federal parliament and all 10 provincial legislatures is not unprecedented. It happened in the case of the 1992 Charlottetown Accord – which was only finally defeated in a popular referendum. Yet Norman Spector, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s chief of staff during the same era, has recently written: “I doubt it will ever be possible to recreate that level of intergovernmental consensus.”

Adrienne Clarkson, Governor General of Canada , 1999—2005, with the Clarkson Cup, which since 2009 has been awarded to the winner of the National Canadian Women's Hockey Championship. Jean Chretien’s rather innovative appointment of Mme Clarkson has been regarded by some as a watershed of sorts in the evolution of the office.

Mr. Spector may or may not be right – just like anyone else who ponders such strange things (regardless of the time he once spent in now faded corridors of power). To imagine that the increasingly archaic place of the British monarchy in the Canadian constitution can never be changed is, it seems quite clear to people like me, to virtually (and quite unnecessarily) give up on any version of a “real country” in Canada at last. And who really wants to do that?

There is nonetheless no doubt that the constitutional challenges do place important barriers to change in any very near term. Meanwhile, however, Stephen Harper’s still unadopted proposed legislation on “consultations with electors on their preferences for appointments” to the unreformed Senate of Canada (Bill C-43 in one of its incarnations, C-20 in another) does suggest a similar interim form of “elections” for the office of governor general, that would not require any formal constitutional amendment.

Some comments from the Director of Operations, Democratic Reform, Privy Council Office, to the Legislative Committee on Bill C-20 two years ago, help clarify what is involved: “It’s not an election process, that’s correct, in the way we would normally conceive of it. It is really a consultation process. The idea is that the people who are selected from this will have a democratic mandate, but it is not an election process; in fact, the bill is constructed to make sure that the actual selection process and the criteria for selection remain as they are now [ie the final appointment would still be made, formally, by the prime minister], because to change to a fully elected process would require a complex constitutional amendment, which this bill doesn’t do.”

Prime Minister Harper, if he wanted, could introduce legislation for “consultations with electors on their preferences for appointments” to the office of governor general right now. It even seems possible that some opposition parties might find it more difficult to oppose this kind of legislation than similar legislation for consultations on Senate appointments. Mr. Harper could probably still hold such consultations in time for his appointment of Michaelle Jean’s successor.

Canadian Inuit leader Mary Simon is one person frequently suggested as a replacement for Michaelle Jean in 2010. If Stephen Harper were to take up this suggestion (far from a certainty it would seem?), she would be the first aboriginal governor general – though Pontiac, War Chief of the Ottawa, might also be only somewhat fancifully viewed as the self-appointed last governor of the old French regime in Canada, 1763—1766.

He would not be abolishing the British monarchy in Canada by doing this, of course. (He apparently continues to believe in the monarchy’s future.) But he would be “strengthening Canada” (to use the title of Alberta’s old Triple E Senate reform report of the 1980s), with or without a monarchy.

And – just in case his professed monarchist faith does prove misplaced (as I for one believe it must, in some fullness of time) – he would be doing something that would be democratically welcomed by the “65 per cent of Canadians” who think that Canada’s now strictly symbolic ties to the British monarchy “should be severed” at the end of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II.

Of course none of this will happen right now. Mr. Harper will just appoint a new governor general in the bad old-fashioned way – just as he has finally appointed senators, despite once declaring that he would never do any such thing. It seems part of his approach to government to vaguely present vistas of change that he himself has no real intention of (or even interest in?) acting on. He has nonetheless helped the rest of us glimpse new visions of what is possible in the Canadian future of our strongest and best angelic dreams. And this same future may somehow finally give him some credit for that (whether he deserves it or not).

Fantastic article, bit long, but bang on the money. Someone should write a summary version for the masses. I have suggested this very thing in a much less erudite and detailed way (http://wp.me/peHtN-dS).

You make it sound like its a perfectly legal, non-crazy idea altogether, which is good. I have linked this article up on Democratic Reform in Canada (http://democraticreform.feedcluster.com/) and I’d welcome a submission from a whole feed from your site on Senate reform or other democratic reform issues.

[…] Update: For a far more thorough proposal of pretty much the same thing make a cup of tea and go read this great article over at counterweights. […]