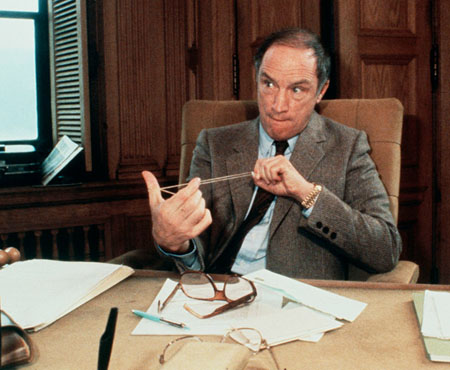

Whether you loved or loathed him, no one is as big as Pierre Trudeau in Canadian politics today

Sep 28th, 2010 | By Randall White | Category: In Brief

The Trudeau family watches as Pierre Trudeau's casket leaves Notre Dame Basilica in Montreal, October 3, 2000.

Tuesday, September 28, 2010 is the 10th anniversary of the death of Pierre Trudeau, 15th prime minister of the modern Canadian confederation (and in office for 15 years, five months, and a little more than one week:1968—1979, 1980—1984). Bruce Cheadle in the Globe and Mail and Randy Boswell in all of the Vancouver Sun, Windsor Star, and Ottawa Citizen (and other Postmedia News outlets?) have composed nicely balanced commemorative articles.

I agree myself with some common themes in these articles. Among we the people, from coast to coast to coast, Trudeau had both strong supporters and strong detractors when he was in office. His one undoubted achievement is the Constitution Act 1982, in the wake of the first Quebec sovereignty referendum of 1980 – with its constitutionally “entrenched” Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Beyond this, it is still too early to say just what his ultimate legacy will prove to be. (His native province of Quebec, eg, has still not “signed” the Constitution Act 1982, even if it has nonetheless used some of the Act’s key provisions, as Jean Chretien liked to point out.)

While agreeing with these common themes, I also have my own increasingly strong opinions about Trudeau – and perhaps about what I hope history will finally judge as his ultimate legacy to the increasingly diverse Canadian people of the 21st century.

I should stress that I was not an especially strong Trudeau supporter for most of his time in office. There were some good things about what Ottawa became during his more than 15-year federal regime. But there were many less than happy things too. Economic policy was not his strong suit (even if he was the son of one of the more successful French Canadian businessmen of the earlier 20th century). And, as the Ontario historian Robert Bothwell quipped years ago, the Montreal-native Pierre Trudeau’s flawed vision of Canada stretched “from one end of Montreal Island to the other.”

It was only during his last years in office that I began to acquire my current very high estimation of his contribution to the Canadian past, present, and future – in spite of all his undoubted flaws and imperfections. I would start in this context with my now quite steely conviction that he was and remains the altogether most interesting prime minister of Canada to date, without the slightest prospect of competition. I am a Canadian political history junkie. And the more I dig into the subject, the more interesting Pierre Trudeau becomes.

* * * *

He came to the job of prime minister with an intellectual and social background quite unlike that of any other Canadian political leader – before or since. Yet he managed to graft this onto the traditions of practical Canadian politics in a way that kept him in office for more than 15 years.

Or, as the Manitoba political humourist Larry Zolf also observed many years ago, Trudeau’s political career proceeded deftly “from philosopher king to Mackenzie King.”

(Where William Lyon Mackenzie King – 10th prime minister of Canada, 1921—1926, 1926—1930, 1935—1948 – was the still unchallenged archetype of practical Canadian political success, but also a monumentally dull and boring lifelong loner, whose most stirring flight of rhetoric was “Conscription if necessary, but not necessarily conscription.”)

Trudeau’s bilingually utopian Montreal-centric vision of Canada was a problem – and will almost certainly prove one of the weakest parts of his legacy. (Though it no doubt is impressive enough when in the Parliament of Canada today you see “Stephen Harper, Jim Prentice and Stockwell Day – all Albertan politicians – answering questions in French.”)

For various good and bad reasons, Trudeau’s reputation became stuck as well with a John-A.-Macdonald high-centralist view of the Canadian federal system, that an only somewhat deeper exploration suggests he did not altogether believe in himself.

(Paul Hellyer resigned from his cabinet because Trudeau had a too decentralist conception of federal housing policy. There is, of course, the so-called “toxic National Energy Program.” But you probably have to be an Albertan politician to become terminally indignant about that. And when Trudeau asked “Who will speak for Canada?” during the negotiations that finally led to the Constitution Act 1982, he was only raising an issue that still needs attention.)

* * * *

Pierre Trudeau was not only more interesting than other Canadian politicians, of his or any other generation, he was also more interested in Canada and the Canadian future.

He actually had a coherent historically-rooted vision of the modern country, that transcended its transitional 19th century status as the first self-governing dominion of the (now fallen, and inevitably obsolete) British empire. It was a flawed vision. But at least it was a vision. What Canadian political leader today is offering anything of the sort?

Trudeau’s vision in this sense had quite a lot to do, I think, with the “northern North American” transcontinental themes that also lie at the bottom of Harold Innis’s local classic of 1930, The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History – still in print, and still the single most interesting book on Canadian history that anyone has written to date.

Trudeau was no kind of serious student of Innis’s work (as best as I can make out). And he only gradually came to appreciate the depths of the northern transcontinental history (from coast to coast to coast) that Innis had first made public when Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau was still just the pre-teenage son of Charles-Émile Trudeau and Grace Elliott, getting excellent grades at the Académie Querbes, 215 Bloomfield Street, Outremont, in Montreal.

Shortly after the 49-year-old “Rt. Hon. Pierre E. Trudeau” first became Prime Minister of Canada in 1968, however, he wrote a short Foreword to his friend Eric Morse’s book, Fur Trade Canoe Routes of Canada / Then and Now: “In Canada we have had few decisive battles and not many dominant leaders. Much more important to our history has been the struggle of nameless Canadians to improve their lives in our often hostile environment. This struggle has produced its share of adventure and heroism … Anyone who wishes to get a feeling for the unique history and geography of this country can do no better than follow Eric Morse’s example.”

(And Trudeau himself was an avid and athletic canoeist, who had travelled many of the old northern transcontinental fur trade routes outlined in Eric Morse’s book.)

* * * *

There is one final virtue of Pierre Trudeau, the unusually interesting Canadian visionary (and at least rational patriot, no doubt), that deserves underlining on the 10th anniversary of his death. For all his alleged arrogance and supreme confidence in his own views, he was a man who was more than willing to learn from his experience – and to adjust his assumptions and beliefs in response to his learning.

Chatting up Princess Diana at a dinner he hosted in Ottawa during her first visit to Canada in 1983 – somewhat more than a year after Queen Elizabeth II had signed the Constitution Act 1982, which for some strange reason did not also abolish the last strictly symbolic vestiges of the British monarchy in Canada.

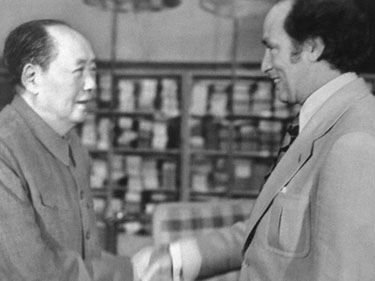

We know now, eg, that he was much closer in his youth to the traditional Quebec or narrow French Canadian nationalism that he ultimately became so famous for transcending, Canada-wide. And we can see that during his time in office as prime minister of Canada his vision of the country’s past, present, and future grew and evolved, as he learned more about the vast and complex diversity of the second-largest geographical territory in the world.

(“Some countries have too much history,” Mackenzie King had wearily observed in the first half of the 20th century: “Canada has too much geography.”)

Early on in his 15-year regime, in a “failed attempt” called the Victoria Charter 1971, Trudeau had tried to “patriate” the Canadian Constitution from the United Kingdom – and provide Canadians at last with their own constitutional amending formula, separate from the British Parliament (which had passed the original Constitution Act 1867, formerly known as the British North America Act). He finally succeeded a decade later with what became the Constitution Act 1982, partly because he learned from past mistakes – and changed in response to his learning.

Among many other things, eg, Pierre Trudeau in the 1980s became much more receptive to the legacies and rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada than he had been in the late 1960s and early 1970s. “We have not yet realized,” Harold Innis had written in 1930, “that the Indian and his culture were fundamental to the growth of Canadian institutions.” We at least began to realize all this in sections 25 and 35 of the Constitution Act 1982.

Randy Boswell has reported in his commemorative article: “‘I think Trudeau’s fate historically will very much depend on whether Canada remains a single country, as it is now,’ says University of Toronto professor John English, whose award-winning second volume on Trudeau’s life, Just Watch Me, is being reissued in paperback this month.” Or, in other words, history will ultimately judge Trudeau positively if his native province of Quebec remains a part of Canada – and negatively if it does not.

There is no doubt something to this argument. But I think the most crucial point is broader again. Pierre Trudeau has left all of us – in every province and territory, from coast to coast to coast – with an admittedly flawed vision of a Canadian future that has already been constructively changed and adapted, in response to various forms of contemporary learning from past mistakes. Continuing to fix and adapt and update and improve this flawed vision, it seems to me, is still the best chance we the diverse, multicultural, and bilingual Canadian people have for a vigorous and prosperous future in the 21st century.

If we carry on with this challenge, both Pierre Trudeau’s historical reputation and we the Canadian people ourselves will prosper. Not everyone in Canada today believes this, of course. But that is just part of the vision of diversity too. And those who violently disagree must at least propose some sensible alternative to the broad direction in which Trudeau pointed us (and that, in one way or another, we continue to follow today – because no one has in fact proposed any kind of alternative that seems at all likely to work: including all of Mr. Harper, Mr. Ignatieff, Mr. Layton, M. Duceppe, and Ms. May).

* * * *

If you happen to be in the Toronto area over the next few weeks, note that images from Helen Branswell’s new book Trudeau are on display until October 16 at the IX Gallery, 11 Davies Avenue, in the Queen-Broadview area. (Davies Avenue runs north off Queen, just east of the bridge across the Don River.)

Nice piece – and bang-on assessment of Trudeau’s “interestingness.”