Senate reform in Canada – “America’s most durable and .. most effective and important enemy of all”

Oct 25th, 2013 | By Citizen X | Category: In Brief

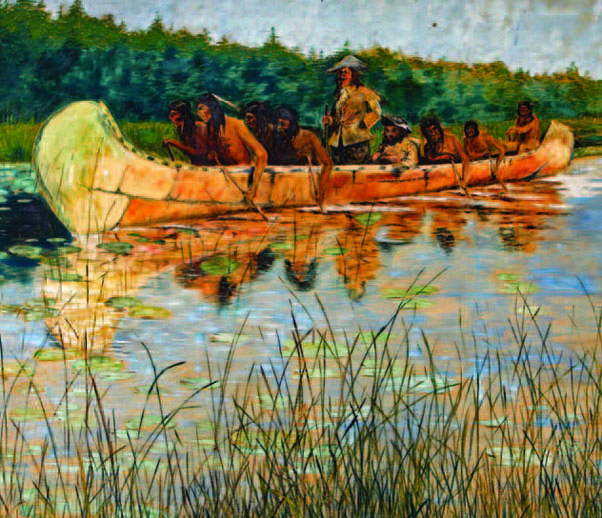

Samuel de Champlain and First Nation allies, near “the lake that he quickly named after himself” in the summer of 1609 – very early days on the Great Warpath.

The news that “the Harper government’s most recent attempt at Senate reform has been declared unconstitutional” by the Quebec Court of Appeal ought to remind us that our Canadian history goes so much deeper than PM Harper’s beloved British monarchy.

(Which is a good thing. According to a recent poll, “younger citizens – those aged 18 to 24 – believe the country’s iconic coffee-and-doughnut shop Tim Hortons has a much more powerful role in shaping Canadian nationhood than the monarchy.”)

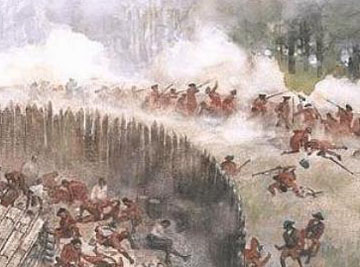

Battle of Great Meadows or Fort Necessity, July 3, 1754, when the French and Indians (aka Canadians) forced the British Americans under a 22-year-old George Washington to surrender – and began what American history still calls the “French and Indian War.”

On some vaguely related historical trajectory, the US conservative military historian Max Boot was taken to task not long ago for observing that “Canada today” is “generally viewed by Americans as a dull but slavishly friendly neighbor, sort of like a giant St. Bernard.” (Objections were raised by both the irrepressible Conrad Black, and the St. Catharines, Ontario history teacher Gerry Boley, writing in the Buffalo News.)

Yet Max Boot made his observation in a review of Eliot A. Cohen’s new book, Conquered into Liberty: Two Centuries of Battles Along the Great Warpath that Made the American Way of War. Contrary to much popular opinion, Boot noted, Cohen’s book “argues that the American approach to warfare originated in battles fought hundreds of years ago along a 200-mile stretch of land and water from Albany to Montreal. The Indians called this the Great Warpath, according to Cohen, and from the early 18th century until the early 19th century, it was the scene of unrelenting conflict.”

Boot goes on : “At first the combatants were British and French settlers, each augmented by Indian allies. Following the French defeat in 1759, Canada became British. Subsequent battles were fought between His Majesty’s Government and recalcitrant subjects of the King who dared to raise the banner of rebellion in 1775 and came to blows with the Mother Country in 1812. Even well into the 19th century there were regular fears of another Anglo-American conflict breaking out.”

And then Max Boot writes : “Canada–today generally viewed by Americans as a dull but slavishly friendly neighbor, sort of like a giant St. Bernard–always seemed to be either a place to launch or target an invasion. Cohen neatly captures this counterintuitive reality when he announces in an author’s note that, after having worked as a government official to counter threats from Iran and the Taliban, he was eager to finish this book, ‘which deals with America’s most durable, and in many ways most effective and important enemy of all.’ By which he means Canada.”

Lester Pearson (left) and Lyndon Johnson, on a somewhat happier occasion in 1966 – and in Canada, where the carpet belonged to the Canadian prime minister.

Something of this Canada, which is “America’s most durable, and … most effective and important enemy of all,” has even survived into the 20th and 21st centuries. It is the Canada that did not join the United States in Vietnam – or Iraq. It is the Canada that prompted Lyndon Johnson to grab Lester Pearson by the lapels of his suit jacket (after Pearson had spoken out against the Vietnam War stateside), and hiss “You pissed on my carpet.”

We have not seen much of this ancient Canada of the Great Warpath since January 23, 2006 – despite what is sometimes said about the Keystone Pipeline. It is a very North American Canada that many Americans have come to value, as a counterweight to various downsides of life in the USA today. If we seriously believed in the future of this Canada today, we would democratically reform the unreformed Senate of Canada, and turn it into something useful at last. And we wouldn’t hesitate to use the provincially representative constitutional amending formula that the Quebec Court of Appeal has prescribed!