Our Lady of the Snows, 1911—1921

Aug 11th, 2017 | By Randall White | Category: Heritage Now

In his Oxford History of the American People the controversial New England historian Samuel Eliot Morison wrote that “the ‘King and Country’ argument was freely employed” in the 1911 Canadian federal election campaign. And “one of Rudyard Kipling’s worst poems, ‘Our Lady of the Snows,’ was widely circulated to rebuke the impudent Yankees.”

Ironically enough, the poem had originally been composed to celebrate Wilfrid Laurier’s Imperial Preference tariff of 1897 — by a man George Orwell would later call “a jingo imperialist,” who was nonetheless “a good bad poet.” The at least musical first lines were : “A Nation spoke to a Nation, / A Queen sent word to a Throne: / ‘Daughter am I in my mother’s house, / But mistress in my own.”

* * * *

Part of the Canadian opposition to the proposed 1911 Canada-US Reciprocity Agreement probably did have something to do with nascent patriotic feelings about Canada as what would later be called a Britannic nation. Some 56% of the dominion’s 1911 population of more than 7.2 million people reported British origins.

(Another 29% reported French origins. The remaining 15% included First Nations and some with African and Asian origins, but its great bulk was now “Other European” — with Germans, Scandinavians, Ukrainians, and Italians the most numerous.)

On somewhat different tribalist values, various already potent regionalisms might want to stress that the Borden Conservatives opposing reciprocity took 85% of all Ontario seats in the 1911 election (with just over 56% of the provincial popular vote). At the same time, the Conservatives also took 80% of the seats with 52% of the vote in Manitoba — and every seat in British Columbia, with 59% of the vote.

Even the Laurier Liberal stronghold in Quebec, where the francophone majority had very few patriotic feelings about any aspiring Britannic nation, faltered somewhat in 1911. The Liberals had taken 75% of the Quebec seats in 1896, 88% in 1900, 82% in 1904, and 83% in 1908. In 1911 they managed a mere 59% — more like the 57% of 1891.

Laurier’s biggest problem in his home province was that, by the end of the first decade of the 20th century, it was clear enough he had paid a price for the privilege of serving as first French Canadian prime minister of the British North American confederation of 1867.

Joseph Schull later explained how the nationalist Henri Bourassa had come to view “Sir Wilfrid Laurier,” by the time Le Devoir began publication in January 1910 : “The man who proposed the navy … was the man who had sent Canadian troops to South Africa and abandoned the cause of separate schools in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Laurier had ‘veiled in golden clouds the betrayals, weaknesses, and dangers of his policy’.”

Under Laurier, in particular, George-Étienne Cartier’s dream of a modern Canadian West hospitable to Canada’s historic French Catholic culture — and the multiracial fur-trade past of the First Nations and the Métis — was sacrificed to the dream of a francophone prime minister.

Laurier’s compromises, effectively abandoning any hints of federal government support for Catholic education and the French language outside Quebec (except for the Ontario Catholic separate schools enshrined in what is now the Constitution Act, 1867), began with the Manitoba schools question in the 1890s. They carried on in the new provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, created from the Northwest Territories in 1905.

* * * *

There was a further mythic force on the anti-reciprocity side of the 1911 federal election, also appreciated by the controversial late New England historian Samuel Eliot Morison (1887–1976).

In Morison’s words, House of Representatives “Speaker Champ Clark [a Democrat] helped whip up Canadian sentiment against” the proposed trade deal, “by a stupid speech in which he predicted that reciprocity would be the prelude to planting the Stars and Stripes over ‘every foot’ of North America.” And “an obscure congressman proposed that [Republican President] Taft be instructed to open negotiations with Great Britain for the annexation of Canada.”

In the end, however, the defeat of both Laurier and his government’s proposed Canada-US Reciprocity Agreement in 1911 did not at all stop the growth of increasingly stronger Canada-US “foreign trade” ties over the next four decades.

In 1870, with memories of the original 1854–66 Reciprocity Treaty still in the air, 51% of Canadian exports had gone to the United States and only 38% to the United Kingdom.

By 1910 this relationship had reversed, with only 37% of exports going to the US and 50% to the UK.

By 1930, however, 45% of Canadian exports went to the US and only 27% to the UK. By 1950 65% were going to the US and only 15% to the UK. Notwithstanding the allure of “one of Rudyard Kipling’s worst poems,” by the middle of the 20th century Canada’s British trading connections would be much diminished from 1911.

* * * *

Like Laurier himself in an earlier era, Robert Laird Borden from Nova Scotia spent some time as Conservative leader learning the ropes and being defeated by Laurier — before finally becoming federal prime minister in the election of 1911.

Borden was a descendant of the family-farm settlers celebrated by John Bartlet Brebner in The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia, first published in 1937. Like Edward Blake (in some respects at least), he had become an affluent leading lawyer in his home province before embarking on a political career.

Despite earlier vaguely Liberal ties, Borden accepted Charles Tupper’s urging to run for the Conservatives in Halifax in the June 23, 1896 federal election. Laurier’s Liberals won across the country. But Robert Borden won one of two seats in Halifax.

Charles Tupper resigned as Conservative leader after his second loss to Laurier, in the November 7, 1900 election. Borden succeeded him in 1901. Then in Borden’s first election as party leader on November 3, 1904 the Laurier Liberals took all 18 Nova Scotia seats, including Borden’s. As explained by biographer Robert Craig Brown : “Borden talked of resigning … But just before Christmas 1904 he decided to remain as party leader … A vacancy was hastily found in Carleton constituency in Ontario and Laurier graciously arranged that Borden be acclaimed on 4 Feb. 1905.”

In the late summer of 1907 Borden announced (as Brown explains, again) “his Halifax Platform — in his words, ‘the most advanced and progressive policy ever put forward in Federal affairs’ … It called, among other things, for reform of the Senate and the civil service, a more selective immigration policy, free rural mail delivery, and government regulation of telegraphs, telephones, and railways and eventually national ownership of telegraphs and telephones.”

(The officially named Progressive Conservative party in Canada would not arrive until December 1942. But Borden owed something to the “Progressive Era 1890–1920” in the United States — and perhaps to the similarly indebted Theodore-Roosevelt side of the US Republican party. And in the true north, strong and free, according to today’s Parliament of Canada website : “The titles ‘Conservative’ and ‘Liberal-Conservative’ were used interchangeably between 1867 and 1942.”)

The Borden Conservatives did better in the October 26, 1908 election. Yet even when facing the progressive Halifax Platform the Laurier Liberals won handily. It would take the exotic blend of British imperial patriotism and Canadian economic nationalism raised by the 1911 Canada-US reciprocity election to finally bring Robert L. Borden’s variation on John A. Macdonald’s old party back to office.

Robert Craig Brown reports as well that from the start of his career Borden “campaigned on the hardy staple of Macdonald-era Tory politics, the National Policy … the plank in the Conservative platform that captured the interest and support of most of his clients.” (And as evidence that not all National Policy supporters lived in Toronto, these clients included the “Bank of Nova Scotia, Canada Atlantic Steamship, Nova Scotia Telephone, and the bread and confectionery business of William Church Moir.”)

* * * *

Borden’s first term in office was seminally interrupted by the First World War that broke out on August 4, 1914. (The first self-governing dominion of the British empire would not make its own declaration of war on Germany. It still just followed the mother country in the United Kingdom.)

In some ways the war nonetheless brought relief to a struggling new government in Ottawa. As Brown and Cook report, “the central fact of Borden’s pre-war administration” was “the obstructionist role of the Senate in his government’s legislative programme.”

The crux of the problem here would be nicely summarized in Robert A. MacKay’s landmark study on The Unreformed Senate of Canada, first published in 1926. As crucial background, recall that Canadian senators are effectively appointed by the federal prime minister. And one traditional result was that long-serving federal governments tended to “pack” the Senate with their own party appointees.

So, in MacKay’s words : “when the Liberals came into office in 1896, the Senate consisted of 63 Conservatives, 10 Liberals and 3 who listed themselves as Independents ; when the Conservatives came into power in 1911, there were 57 Liberals in the Senate and only 17 who listed themselves as Conservatives.”

From a broader “imperial” point of view, Borden’s difficulties getting legislation through a Liberal-dominated Senate in Canada half-followed in the footsteps of difficulties faced by the British Liberal prime minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman a few years before, getting legislation through “the permanent conservative majority in the house of lords.”

According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Campbell-Bannerman was “Britain’s first, and only, radical Prime Minister.” After a long apprenticeship in late 19th and early 20th century UK politics, he finally became prime minister in 1905, only to be removed from office by death too soon in 1908.

Campbell-Bannerman, however, was succeeded by Herbert Asquith, who remained prime minister of “the last Liberal government in British history” (A.J.P. Taylor, English History 1914–1945) until May 1915. Then Asquith formed a wartime coalition government with the Conservatives (aka “Unionists” at the time, favouring Ireland’s remaining in the United Kingdom). Asquith was in turn succeeded as prime minister by the Liberal wild man from Wales David Lloyd George, who presided over a War Cabinet and then another coalition government until October 1922.

Despite his early death, Henry Campbell-Bannerman did “much to help the new democracy introduced by the last Liberal regime at Westminster “to find its feet” (Robert Ensor, England 1870–1914).

Meanwhile, various new democratic plans in the mother country disturbed the “small privileged class” entrenched in the hereditary House of Lords, “which for centuries had exercised a sort of collective kingship, and at the bottom of its thinking instinctively believed that it had a divine right to do so.” (Ensor again — and on this view even democracy just meant male, property-owning commoners voting on whether Whig or Tory aristocrats would run the government.)

All this came to a final head with Liberal Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George’s “People’s Budget” of 1909 (which the House of Lords rejected) and the following two UK elections of 1910 — “the decisive year in settling the rather important and very hard fought question of whether and how Britain would become a modern democratic polity” (Sunder Katwala, 2010).

The second 1910 election led to passage of The Parliament Act 1911 in the UK House of Commons. This “denied to the lords any right to reject any Bill certified by the Speaker of the house of commons to be a money Bill” (George Clark, 1971). It also denied the right of the House of Lords to reject any Bill on any subject, that had been passed by the elected House of Commons three successive times over two years.

The 1911 Parliament Act’s passage by the House of Lords itself was facilitated by the only recently crowned King George V’s agreement to create as many new members of the Lords (peers) as would be required to pass the legislation. This was enough to convince the old peers to grudgingly bless what the new House of Commons had already passed. And this at last unambiguously confirmed the democratic principle that the elected “lower house” of parliament was superior to the unelected “upper house.” (And very quietly, of course, this echoed the revolutionary Rump Parliament’s resolution of January 4, 1649 — 26 days before Charles I was beheaded : “the people are, under God, the original of all just power,” and “the Commons of England in Parliament assembled, being chosen by and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation.”)

* * * *

The 1911 Parliament Act in the United Kingdom also alluded briefly to future plans for a broader reform of the House of Lords, that would remain dormant until the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Robert Borden’s broader plans for Senate reform in Canada were not much more successful.

The Canadian Senate was not home to a hereditary landed aristocracy (though its members were at this juncture appointed by the federal prime minister for life). It was more of a blend of the House of Lords in the United Kingdom and the Senate in the United States. And during Borden’s early years as prime minister the 17th Amendment to the US Constitution established the popular election of American Senators.

(How quickly such things could happen back then! The Amendment was proposed by Congress in 1912, adopted in 1913 after ratification by three-fourths of the state legislatures, and then implemented nationwide in the November 1914 US elections. Before this American Senators were chosen by state legislatures.)

In Canada Robert Borden “is said to have mulled over an elected Senate in 1914.” What he finally managed to achieve — in 1915 — was just an extension of the original three 24-member Senate sections for each of Atlantic Canada, Quebec, and Ontario, to include a fourth 24-member section for Western Canada.

The original three 24-member sections of 1867 descended from the old (and after 1856 even elected!) Legislative Council of the United Province of Canada, with 24 members each for Canada East (the future Quebec) and Canada West (the future Ontario). The addition of two British North American Atlantic or Maritime provinces in 1867 constituted a third regional section in the new Senate of the Dominion of Canada. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick each had 12 of the 24 Atlantic seats to start with. When the micro province Prince Edward Island joined in 1873 it took four of these seats, leaving Nova Scotia and New Brunswick with 10 each.

At first the practice with the new Western Canada that blossomed after 1867 (and especially after 1896) was more random. The federal government assigned Manitoba two Senate seats when it was created in 1870. British Columbia acquired three seats when it joined in 1871. And in 1905 each of Saskatchewan and Alberta were given four seats. Then Robert Borden did manage to establish a new 24-member section for Western Canada in 1915, with the four 20th century provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia taking six seats each.

Whatever its intention, this change did not strengthen the regional representation of the rapidly growing new region of Western Canada in Ottawa. Each of Atlantic Canada (or the Maritime Provinces), Quebec, Ontario, and Western Canada now had 25% of the seats in the Senate. Yet, as of the 1921 census, Ontario had 33.4% of the Canada-wide population, Western Canada 28.2%, Quebec 26.9%, and Atlantic Canada 11.4%. Only Atlantic Canada actually fared better in the Senate than in the Canadian House of Commons, where representation by population prevailed.

Harold Innis would similarly observe in the late 1940s : “Our constitution has proved inadequate in the face of the demands placed upon it. The Senate, that unique institution, has lent itself to political manipulation. As a guarantee of maritime rights, the Maritime Provinces were given a substantial number of senators. They have supported the growth of a strong party organization.”

* * * *

According to the Canadian War Museum : “Some 619,636 Canadians enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force” in Europe during the First World War (4 August 1914–11 November 1918).

Of those who enlisted, “approximately 424,000 served overseas. Of these men and women, 59,544 members … died during the war, 51,748 of them as a result of enemy action. The small Royal Canadian Navy reported 150 deaths from all causes. No accurate tabulation exists for Canadians who served as volunteers in the Royal Navy or British Army. An additional 1,388 Canadians died while serving with the British Flying Services.”

Unlike the United States (which did not join in until early April 1917), Canada was in the First World War from the start, as part of the global British empire. Its war deaths accounted for more than 0.80% of its total population, compared with only 0.13% in the USA.

To some extent, the war did help Borden’s Conservative regime pull itself together as well, and arguably prolonged at least Robert Borden’s career as prime minister. For the growth of Canadian democracy the government (or more exactly governments) he presided over until 10 July 1920 left as many as half a dozen notable legacies — pro and con.

Democratic franchise extension and the Dominion Elections Act, 1920

In 1898 the Laurier Liberal government had returned John A. Macdonald’s federal electoral franchise of 1885 back to the provinces, so to speak (while also “prohibiting provincial disqualification based on race or socio-professional characteristics”).

This enlarged the number of adult men eligible to vote, since most provinces had more expansive democratic franchises than the first Conservative prime minister in Ottawa had thought appropriate.

If not entirely by design, however, it was the Borden Conservative government of the early 20th century that finally brought in something at least close to the ideal modern democratic electorate of all adult males and females. (Though there would remain both invidious and arguably sensible exclusions of certain groups in the adult population — from “Indians on reserves” to “judges, prisoners and people with mental disabilities”).

Here again, the Borden government was nudged along by the 1914–1918 global conflict. According to Elections Canada today: “The First World War brought the greatest changes to the federal franchise.” To start with, in 1915 and especially 1917 the right to vote was extended to “military electors in active service,” including women and “Indians.”

Elections Canada goes on : “Surprisingly perhaps, this extension of the franchise was not a recognition of basic rights. Rather, the Unionist government of Sir Robert Borden was acting to give the vote to groups seen as likely supporters, including Canadians on active military service and their female relatives at home. The same legislation also took away the franchise from likely opponents, such as conscientious objectors, Mennonites and Doukhobours [from Russia],” and recently naturalized Canadian residents “from non-English speaking countries.”

Democracy in Canada was nonetheless making broader progress: “In 1918, the franchise at federal elections was further extended to all women 21 years of age and over. The following year … women became eligible for election to the House of Commons.” And finally : “In 1920, a new Dominion Elections Act created the office of Chief Electoral Officer. From this point onward, the federal franchise would be established by federal, not provincial, law.” And something still closer to universal adult suffrage was at least well within sight (or ought to have been!)

The Nickle Resolution

The same progressive wartime political climate – asking virtually all adults to assume unusual burdens of one sort or another – also prompted the intriguing quirk of Canadian law and public policy known as the Nickle Resolution. (And some 80 years later this would prevent media mogul Conrad Black from retaining his Canadian citizenship while accepting the British title, “Lord Black of Crossharbour.”)

According to Christopher Paul McCreery, “there are four entities – Privy Council Order 668, NickIe’s original resolution, NicMe’s resolution as amended, and the Report of the Special Committee [1919] — that are confusingly bound up with what is today remembered as the Nickle Resolution.” It is clear enough, however, that William Folger Nickle was a maverick idealist from John A. Macdonald’s “loyal old town” of Kingston, Ontario — MP for Kingston, 1911–1919, and subsequently an Ontario provincial cabinet minister, 1923–1926 (and then father of another Ontario cabinet minister, in the 1950s and early 1960s).

To make McCreery’s story very short, during the war the Kingston MP W.F. Nickle “was appointed to chair a special committee of the House of Commons to examine the question of the appointment of honours.” As the collective authors of Wkipedia see the matter today : “In 1919, Nickle moved and had passed through the House a resolution calling for an end to the practice of Canadians being granted knighthoods and peerages.”

Some wonder about the exact legal status of this Canadian House of Commons resolution today. (It was never sent to the Senate, eg.) Yet except for a brief revival during the Conservative government of R.B. Bennett in the first half of the 1930s, the practice of bestowing British titles on eminent Canadian politicians and businessmen, as in Sir John A. Macdonald, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Sir Henry Pellat, and even Sir Robert Borden, did come to a suitably democratic end.

French-English conflict and conscription

According to the late historian of early 20th century Canada, Ramsay Cook, Robert “Borden discovered, like Laurier before him, that governing was a delicate balancing act. But his problem was greater … for his party was an uneasy alliance of enthusiasts for empire and anti-imperial French Canadian nationalists.”

The First World War left a similar mark on Canadian democracy, by dramatically underlining tensions between the French-speaking majority in Quebec and the English-speaking majority in the rest of the country.

Laurier’s own effective abandoning of George-Étienne Cartier’s hopes for a Canadian West that was hospitable to the deep French and Indian past was part of the background. (And so was the “Regulation 17” imposed by the Whitney Conservative provincial government in Ontario, abolishing the use of French as a language of instruction beyond the first two years of elementary school.) But it was the Macdonald Conservative party that hanged Louis Riel in 1885 which ultimately blossomed in the Canadian federal election of December 17, 1917 – in many ways a more poignant bow to the longer term future than either 1891 or 1911.

The Dalhousie University political scientist Murray Beck set down an astute short account of the 1917 election in the late 1960s. The saga began when Prime Minister Robert Borden returned from a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet in London, England in May 1917, and “decided that conscription [or compulsory military service] was the only answer” to what at least some saw as urgent manpower shortages in the First World War.

* * * *

Conscription was in some degree a controversial issue in all parts of the country. But it was especially disliked in French-speaking Quebec. Some English-speaking Canadians have had trouble understanding Quebec’s attitude to the two world wars that haunted the first half of the 20th century. The French Third Republic in Europe (and its Asian and African colonies) was on the same side as the global British empire. Why didn’t French Canadians support the war like English Canadians?

Yet in an age dominated by mass political communication through newspapers (and then even radio, phonograph records, and movies) French Canadians tended to see both world wars as just “another typically British imperialist intervention,” on the model of the South African War of 1899–1902 — “Canada’s first foreign war” during the sunny days of the Laurier Liberal government. Most French Canadians were concerned about the defence of Canada, not the global British empire. In some ways they resembled the American isolationists who kept the United States out of the First World War until April 1917.

Along with dividing the country, what finally became Borden’s Military Service Act, passed early in July 1917, also divided the federal Liberal party. In an effort to bolster support for the controversial introduction of compulsory military service (and perhaps with the example of the United Kingdom coalition since May 1915 partly in mind), Borden proposed a wartime coalition government of the two major parties in Canada to Laurier. Understanding what a disaster this would be for his support in Quebec, Laurier declined. At the same time, some of his colleagues from English-speaking provinces did support conscription, especially in Ontario and (even more especially) Western Canada.

Murray Beck picks up the story from here : “The western Liberals came into the government on October 12, and everything was now in order for the election which Borden called for December 17.” (Laurier had also turned down Borden’s proposed further extension of the parliament elected in 1911, which had already been extended past the traditional five-year maximum, under constitutional provisions for times “of real or apprehended war, invasion, or insurrection.” This meant that the 1911 parliament had to be dissolved in the fall of 1917, and Robert Borden’s new “Unionist” government in Canada had to call a fresh election.)

* * * *

If one were looking for quite such a thing as a “rigged election” in the history of the 1867 Canadian confederation to date, the “Khaki Election” of December 17, 1917 would come closest to filling the bill.

Elections Canada hints at all this when it notes that the wartime “extension of the franchise was not a recognition of basic rights. Rather, the Unionist government of Sir Robert Borden was acting to give the vote to groups seen as likely supporters, including Canadians on active military service and their female relatives at home.” Murray Beck’s political science colleague J.R. Mallory was more direct in his Canadian government textbook : “The Union government carried two measures through Parliament in 1917, the Wartime Elections Act and the Military Voters Act, which, as Professor Ward puts it, ‘could hardly fail to return a majority in Parliament for the party which enacted it.’”

Beck’s measured conclusion notes that the “Unionist member for Red Deer … admitted at the time that the methods were ‘somewhat crude’ … More recently, C.G. ‘Chubby’ Power [a former hockey player elected as a Laurier Liberal in Quebec in 1917] has refused to ‘attach much condemnation to the acts of fraud’” enabled by the Wartime Elections Act and the Military Voters Act, “because of the tide of sentiment running in favour of ‘the patriotic cause.’”

The late Murray Beck (1914–2011) carries on : “Certainly the public refused to get excited about the manipulation … it apparently felt that the war was all that mattered. It is going too far to say that tactics of this kind won the election. A more correct generalization would be that the opinion moulders in English Canada, especially in Ontario and the West, determined the result. They dinned it into the head of the ordinary citizen, who was not all that enthusiastic about conscription, that to demonstrate his loyalty to Britain, maintain Canada’s self-respect, and keep faith with Canada’s fighting men, he had no choice but to vote for Borden, the more so because French Canada was not prepared to do its duty.”

Failure of coalition government

With the fog of war at last dispelled, the kind of extreme political manipulation enabled by the Wartime Elections Act and the Military Voters Act of 1917 disappeared into the more principled and democratic federal electoral system of the 1920 Dominion Elections Act. But meanwhile it no doubt did help give the Borden Unionist government close to two-thirds of the seats in the Canadian House of Commons in the election on December 17, 1917.

(And Murray Beck has also given a crisp example of the manipulation at work. The 1917 “civilian vote” in the Maritimes at first gave all four PEI seats and 9 of 16 in Nova Scotia to the Laurier Liberals. After the more government-friendly “military vote” engineered by the Wartime Elections and Military Voters acts was added in, the Liberals took only two seats in PEI and five in Nova Scotia.)

In raw numbers the magnitude of Robert Borden’s second election victory, as prime minister of a Conservative-Liberal coalition or Union (Unionist) government, very aggressively determined to help win the First World War, ought to have meant a uniquely strong federal government in Ottawa. Yet this numerical strength virtually left out altogether the 29% of the Canadian population still reporting French origins — and in no small part still descending from people who had been calling themselves “Canadien” for more than 225 years.

Canada-wide, Borden’s Unionists took almost two-thirds of the seats with 57% of the popular vote. But in Quebec the Laurier Liberals took 95% of the seats with 73% of the popular vote. And as Murray Beck would much later explain : “For the first time since Confederation, Quebec had failed to elect a single French-Canadian Conservative ; for the first time, too, the party’s popular vote fell below 40 per cent [it was not quite 25% in fact]. Previously Laurier had created a ‘solid Liberal’ Quebec, but it had been in seats only. Now the province was veering that way in popular vote as well.” Moreover, there were also “two New Brunswicks in this election. Apparently, the Anglo-Saxons felt they had to show the flag to the anti-conscriptionist [and French-speaking] Acadian population.”

* * * *

Laurier’s great success in Quebec helped keep the federal Liberal party vital, despite high-profile defections to Borden’s Union government elsewhere. His supporters included the grandson of the 1837 Rebellion leader William Lyon Mackenzie, William Lyon Mackenzie King, who ran and lost for the Laurier Liberals in York North, in the countryside just north of Toronto. Then on February 17, 1919 Wilfrid Laurier suffered a fatal stroke, at the age of 78. And early in August 1919 Mackenzie King succeeded Laurier as Liberal leader at “an unprecedented three-day convention in Ottawa, the first of its kind in Canadian political history.”

As explained by his most recent gifted biographer, Allan Levine (King : A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny, 2011), “Quebec delegates, who respected King’s loyalty to Laurier two years earlier” were almost certainly crucial to Mackenzie King’s third-ballot win. And the new Liberal leader would finally win both the exurban Toronto riding of York North, and a strong minority government in Ottawa for the Liberal Party of Canada, in the 14th general election of the 1867 confederation, on December 6, 1921.

Meanwhile, the end of the First World War on November 11, 1918, had already begun to loosen the glue holding Robert Borden’s Unionist coalition government together. The Toronto businessman William Thomas White had served as finance minister since the 1911 election, and launched the Canadian federal income tax as a supposedly temporary wartime measure in 1917. He also served as acting prime minister while Borden was in Europe from November 1918 to May 1919, trying to help forge a more peaceful international future. Yet it seems William Thomas White had never enjoyed politics. He left the Unionist cabinet over a budget controversy in the summer of 1919.

Some who stayed in the government urged White to replace Borden as full-time prime minister in 1920, but he was not interested. Borden himself was losing interest (and had received medical advice to change his profession). He resigned as prime minister in July 1920.

On his own ultimate recommendation, he was succeeded, as prime minister and leader of what was officially renamed the National Liberal and Conservative Party, by Arthur Meighen — a Toronto-trained lawyer from southwestern Ontario who had moved to Portage la Prairie, Manitoba. As Murray Beck would later explain, the “real loser” of the unprecedentedly divisive 1917 election “was to be Arthur Meighen.” (And the ultimate winner would be William Lyon Mackenzie King, who had loyally lost in York North in 1917 for the Laurier Liberals.)

By this point it was clear enough that the wartime coalition government had no serious political future (Meighen’s “National Liberal and Conservative Party” notwithstanding). Apart from John A. Macdonald’s first non-partisan cabinet of 1867, it has so far proved the only coalition government in the history of the confederation. It did not finally work out well for the politicians who invented it. And it sometimes seems to have given coalition governments generally a bad name in Canada.

Failure of Borden’s imperial federation lite

During his time as Prime Minister of Canada Robert Borden experimented with something else that would have at best a limited future. The early 21st century might anachronistically call it “imperial federation lite.”

Borden was more interested in quite aggressively supporting the global British empire than Laurier. But he thought the Canadian reward for this support should be more influence in imperial decision-making for the self-governing dominions Canada had pioneered. The meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet from which Borden returned in May 1917, convinced about the need for conscription in Canada, was a case in point.

This War Cabinet had almost the same membership as the Imperial Conferences that began in 1907 — the United Kingdom and the five (later six) self-governing dominions of the global empire. Two representatives were added from India, which would not become a dominion until 1947 (including one actual Indian, the Maharaja of Bikaner, Ganga Singh).

After the First World War there were further Imperial Conferences on the model of the 1907 meeting. The definition of this institution on Britannica.com today suggests its limited future : “Imperial Conferences, Periodic meetings held between 1907 and 1937 by the dominions within the British Empire … Convened to discuss mutual defense and economic issues, they passed nonbinding resolutions … After World War II, meetings between the countries’ prime ministers replaced the conferences.” (There would similarly be no Imperial War Cabinet during the Second World War : “British prime minister Winston Churchill was unenthusiastic … Canadian prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was concerned that the idea would be a step towards Imperial Federation, which he opposed.”)

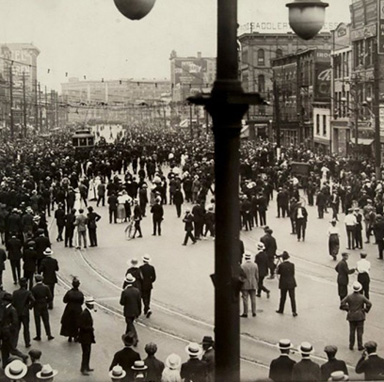

Beyond the Winnipeg General Strike

In the immediate wake of the First World War, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia today : “Massive unemployment and inflation, the success of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and rising Revolutionary Industrial Unionism all contributed to” the Winnipeg General Strike, from May 15 to June 25, 1919. The Borden Unionist government, led by “Senator Gideon Robertson, minister of labour, and Arthur Meighen, minister of the interior and acting minister of justice,” finally “arrested 10 leaders of the Central Strike Committee.”

The Encyclopedia goes on : “Four days later, a charge by Royal North-West Mounted Police into a crowd of strikers resulted in 30 casualties, including one death.” It “ended with federal troops occupying the city’s streets … Faced with the combined forces of the government and the employers, the strikers decided to return to work on 25 June.”

If it was less than friendly towards the early organized labour movement in Canada, the post-1917 election Borden government did have other more progressive sides. In 1918, biographer Robert Craig Brown has explained, a new Civil Service Act was “quickly passed to start the process of removing the outside service … from appointment by patronage. The Dominion Bureau of Statistics was organized to provide … systematic information about the nation’s population, social structure, and economy.” And the “government also established daylight saving time.”

At about the same time that Borden returned from the crucial May 1917 meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet, a royal commission on the future of Canadian railways he had earlier appointed brought down an influential report.

By this point, intoxicated by the economic take-off to “technological maturity” and “high mass-consumption” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Canada had acquired not just one or even two but three transcontinental railways (the original Canadian Pacific, and then a new Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Pacific). The First World War suddenly made clear that 20th century Canada may or may not need two transcontinental railways, but it certainly did not need three.

As the Canadian Encyclopedia today would much later explain on this front, the “royal commission, headed by Sir Henry Drayton and British financier W.M. Acworth … recommended the nationalization of all railways except the CPR. By the 1920s, the Canadian Northern, Intercolonial, Grand Trunk Railway, and Grand Trunk Pacific were brought together to form the [new public enterprise] Canadian National Railways (CNR).”

* * * *

In the very end the most prophetic part of “one of Rudyard Kipling’s worst poems” – still subtitled in some versions “(Canadian Preferential Tariff, 1897)” – would probably be its lesser known (and less immediately sonorous) fourth stanza :

“‘I called my chiefs to council / In the din of a troubled year; / For the sake of a sign ye would not see, / And a word ye would not hear. / This is our message and answer; / This is the path we chose: / For we be also a people,’ / Said our Lady of the Snows.”

FROM

Children of the Global Village

Democracy in Canada Since 1497

Randall White

eastendbooks 2024

(For background on the larger series of which this is a part, see The Long Journey to a Canadian Republic.)

PART III

DOMINION OF CANADA, 1867–1963

4

“Daughter am I in my mother’s house” … The opponents of reciprocity (and/or Laurier) … Champ Clark and US annexation … Robert Borden’s early career … Senate obstruction of early Borden government … Parliament Act 1911 in United Kingdom … Western Canadian Senate section … Canada in the First World War … Democratic franchise extension … Nickle Resolution … Conflict over conscription … Coalition government … Imperial federation lite … Beyond the Winnipeg General Strike